How Studio Sessions Are Evolving: A Modern Look at Creativity, Collaboration, and Access

There’s been a steady shift in how studio sessions are structured. Not long ago, it was common for a label to book a studio for weeks or even months at a time, with artists writing, recording, and producing an entire album in one place. That still happens, but far less often. These days, studio sessions are more likely to be shorter, focused, and part of a wider, ongoing process rather than a single, self-contained block.

This change reflects the way music is now made. Tracks are often written and developed across multiple sessions, with different studios used for different parts: vocals in one place, drums in another, strings or additional production elsewhere. It’s not necessarily about squeezing things in, though that does happen, but about fitting into a more collaborative, fast-moving, and constantly evolving way of working.

From Start-to-Finish to Piece-by-Piece

Albums and singles are rarely built in one studio from start to finish anymore. Instead, what’s more common is a song coming together over time, through different sessions that may be spread across studios, weeks, or tour dates. An artist might record vocals in a studio between shows. A band may track drums in one studio, then book a different space for overdubs when schedules allow.

This approach has developed in part because of how collaborative music has become. Many songs today have multiple writers and producers. Coordinating everyone’s availability, especially when artists are also performing, promoting, or working on several projects, means the idea of a single, long session is less practical than it used to be.

Studios now play a more modular role in the process. One session might be used to get vocals down, another for backing vocals or edits, and another for live instrumentation or arrangement work. It’s a puzzle being assembled in stages, with sessions booked to capture specific parts as needed.

The Role of Personal Studios

Another reason for the shift is the increased accessibility of professional-grade equipment. Many producers and artists now have their own studio setups that are more than capable of handling large parts of the creative process, including writing, programming, editing, and even mixing.

This means they don’t need to book a commercial space for every part of the project. Instead, they’re more likely to use professional studios for the parts they can’t easily do themselves, such as recording drums, cutting final vocals, or capturing instruments that require high-end rooms, mic collections, or specialist engineers.

As personal studios have become more capable, professional sessions have become more focused. People come in knowing exactly what they need to do, and studios have adapted to support that kind of workflow.

More Studio Options Than Ever

At the same time, the same advances in technology that have made personal studios possible have also lowered the barrier for commercial studio setups. Many professional studios are now building leaner, more affordable spaces, often purpose-built for vocals, overdubs, or writing sessions, without compromising on quality.

This has opened up more options for artists and producers working on tighter timelines or smaller budgets. Not every session needs a large-format console and live room. Sometimes a well-treated vocal booth with a great signal chain is exactly what’s needed.

And because so many of these newer, more specialised studios operate under the radar, they can be hard to find, especially in a hurry.

That’s where services like ProStudioTime have started playing a role, giving artists and teams a way to connect with studios that fit specific session needs. In a landscape where schedules move quickly and options are increasingly varied, being able to line up the right space at the right time has become part of the workflow itself.

Booking and Discovery Are Evolving Too

In this environment, being able to find and book a suitable studio quickly is crucial. The old system of outdated directories, emails, and calls still lingers, but it’s starting to shift. Artists, producers, and managers often need to make decisions fast, based on availability, location, and what the session requires, whether that’s a solid vocal chain, a good live room, or just a quiet, focused space to get something done.

The more tools that exist to streamline this process, the more efficiently teams can build, adjust, and execute recording plans that align with an increasingly fast-paced release cycle.

What This Means for Studio Professionals

For engineers, studio managers, and producers, all of this means adapting to a more agile way of working. Sessions might be shorter, but they’re no less important and often part of bigger projects with tight timelines.

Communication, preparation, and clarity around what a session is aiming to achieve have become even more important. The engineer might be jumping in halfway through a track’s journey, so being able to work quickly and confidently without always having full context is a valuable skill.

At the same time, this shift has opened up more opportunities. Because music is being made continuously, and in more places, there are more chances to contribute, whether that’s handling a one-off tracking session, setting up for a writing camp, or helping an artist finish a last-minute mix pass before release day.

Looking Ahead

The core of the studio session hasn’t changed. It’s still about getting the best performance in the right environment. What has changed is the shape it takes, the time-frame, the workflow, and the role it plays in a broader, often multi-location creative process.

Whether you’re running a commercial facility, freelancing as an engineer, or working as part of an artist’s wider team, understanding how sessions are evolving helps you stay relevant, responsive, and ready to support the way music is being made now.

Guest Post for SoundGirls.org

Guest Post for SoundGirls.org

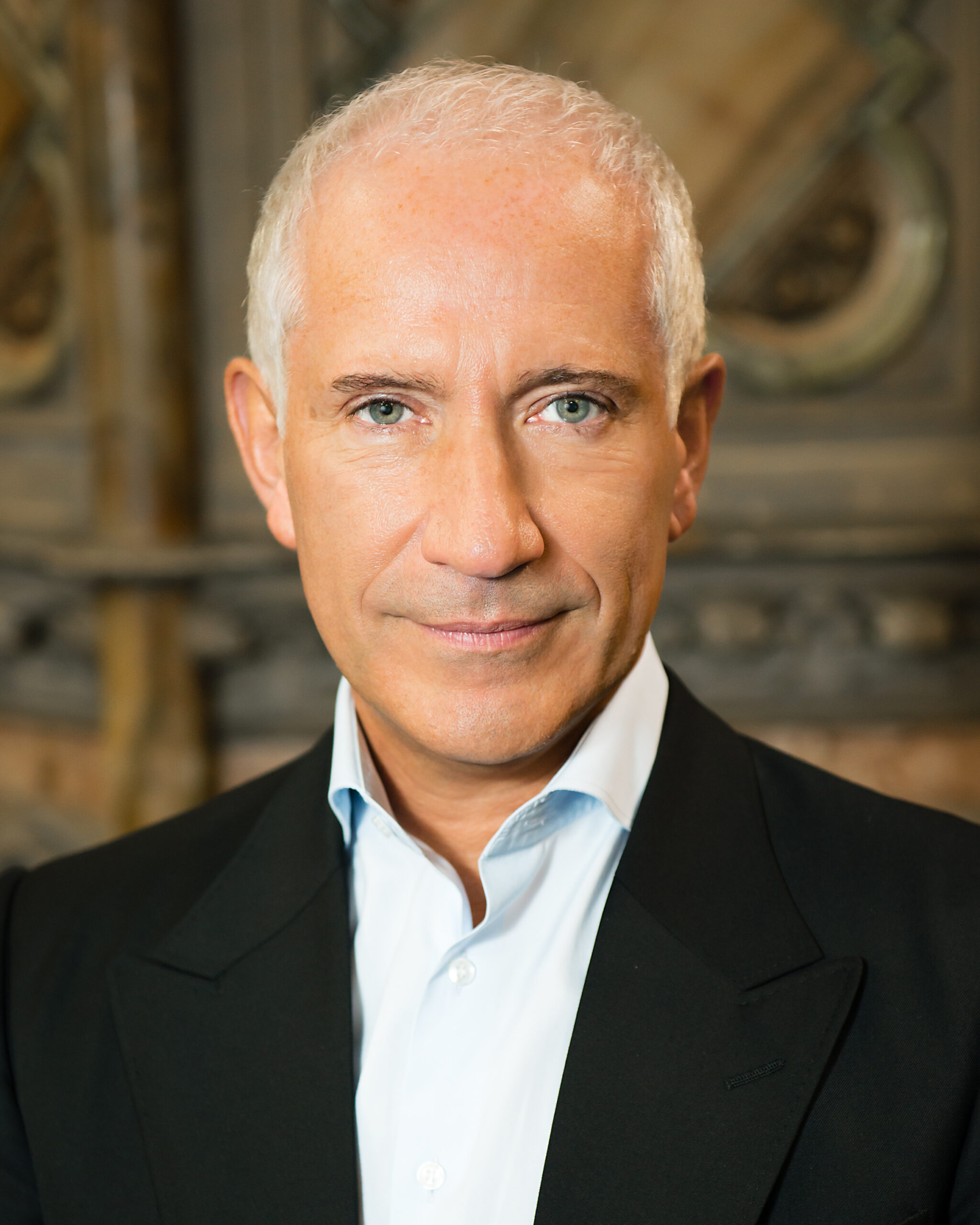

Sam Rudy is a London‑based studio specialist and entrepreneur who lives and breathes recording spaces. As the founder of Pro Studio Time, Sam helps artists, managers and labels book the perfect studio anywhere in the world—fast, transparently and hassle‑free. Before launching his own platform, Sam spent over a decade at Miloco Studios, rising to Studio Manager and overseeing a roster of 160+ world‑class rooms, including London stand‑outs such as The Church Studios, Sleeper Sounds and Baltic Studios. While completing his master’s degree, Sam carried out policy research: in 2015 his thesis “Blank Media Levies … Who Pays?” was published by the now‑defunct MusicTank; he was subsequently invited by Hypebot to write an op‑ed expanding on its findings.A lifelong music obsessive and occasional DJ, Sam is happiest where great acoustics, analogue gear and good coffee meet. When he isn’t matching clients with studios, you’ll find him tending to his allotment, swapping patch cables for pumpkin seedlings.