Guide the Viewer’s Attention

This is my guiding objective in every stage of the mix process and is arguably the most basic and important creative goal in the sound mix. By manipulating the levels of the dialogue, sound effects, and music of each moment you can highlight or bury the most important things happening on screen.

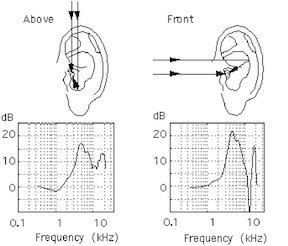

Here’s an example: Imagine two characters are having a conversation on screen. They are standing in a ruined city block after a big battle or disaster. The characters are positioned in the foreground of the shot, and in the background maybe there’s a fire burning and a couple of other people digging through some rubble.

In order to guide the viewer, we want to place the character dialogue in the foreground of the mix. It should be one of the loudest elements, so the viewer can focus on it without distraction. The fire crackling or sounds of people walking through the rubble in the background can be played very low or left out if needed.

If we mix the scene so that we can hear every sound element equally, the viewer may become distracted or confused. The footsteps, rubble, and fire sound effects of the background will compete with the dialogue of the on-screen characters delivering the exposition. By keeping the dialogue clear and present we are telling the audience “this is an important piece of the story, pay attention to this.”

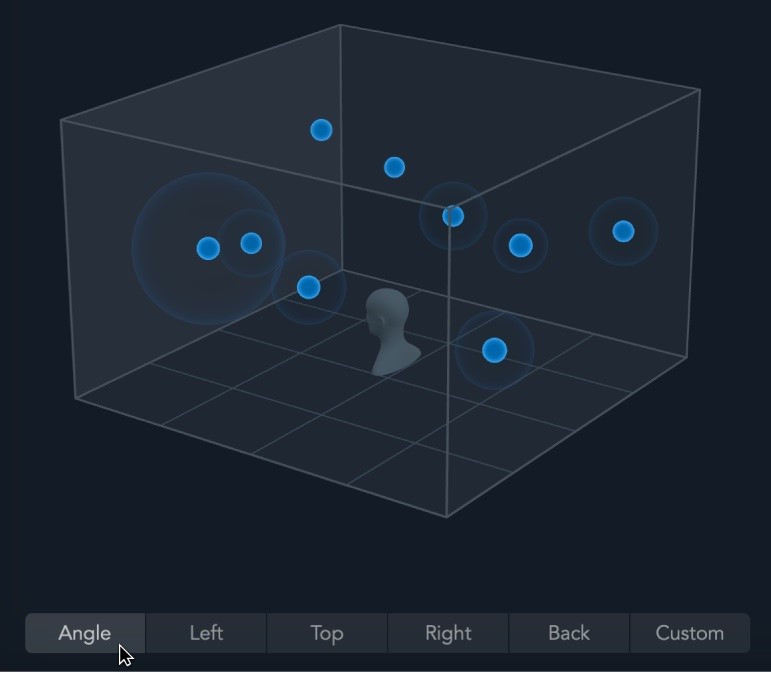

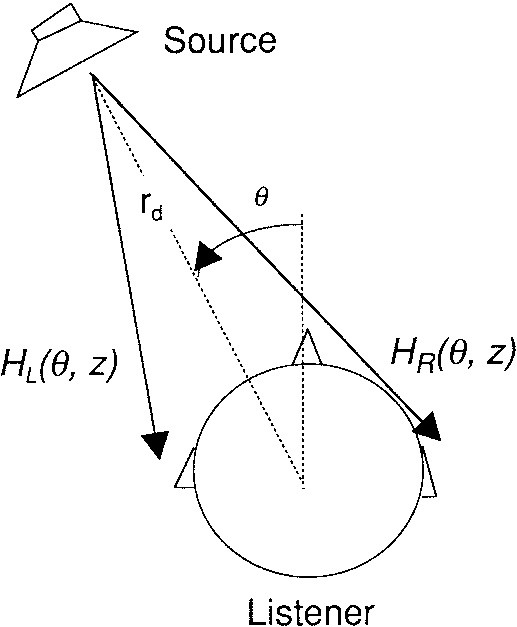

Depiction of a conversation in a distracting scene.

You can achieve the same guidance with sound effects and music if they are delivering important story information to the audience. Perhaps you need to showcase the rattling wheeze of an airplane engine as it begins to stall, causing the heroes to panic. Or maybe a wide sweeping shot of an ancient city needs the somber melody on the violin to help the audience understand that the city isn’t the vibrant, thriving place it once was.

Get the Mix in Spec

This is not a very exciting or fun goal for most, but it may be the most important one on this list. Every network or streaming service has a document of specifications they require for deliverables, and as a mixer, it is very important that you understand and conduct your mix to achieve these specs. If you breach these requirements, you will likely have to correct your mix and redeliver, not ideal.

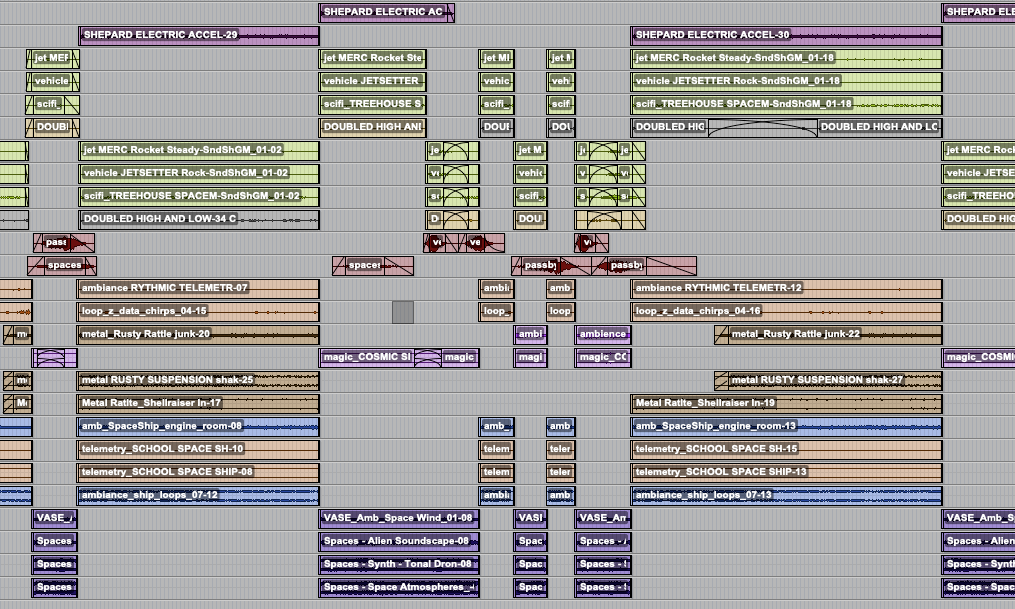

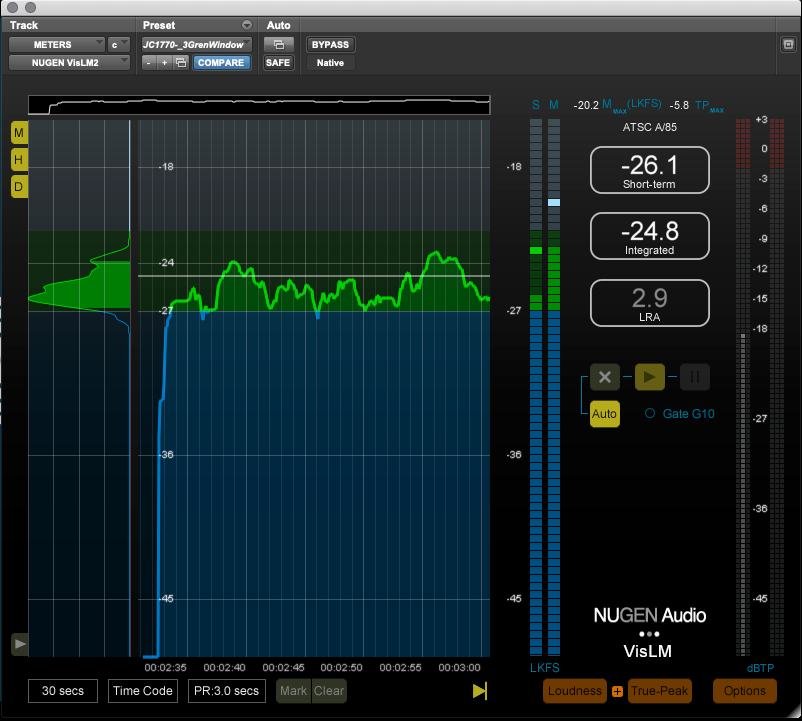

The important requirements I like to keep in mind during the creative mixing process are the loudness specs. These can vary depending on the distribution, but usually, they explain an overall LUFS measurement and a true peak limit, and in most cases, you will have about 4 dB of range you can land in (-22 to -26 for example).

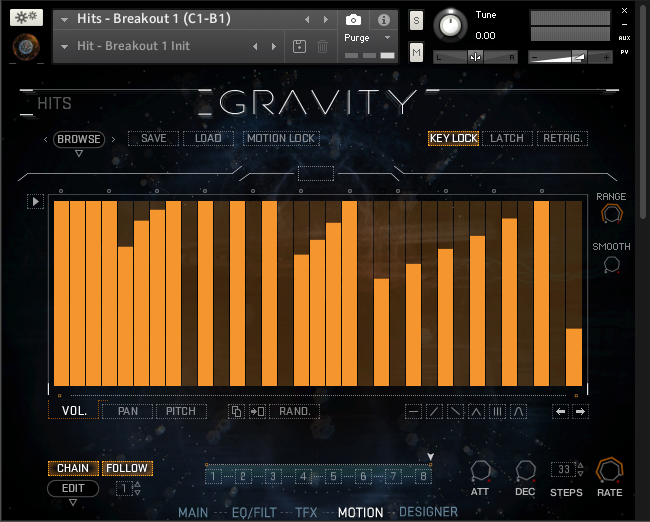

Depiction of LUFS measurement.

The key is to set yourself up for success from the start. I always start my mix by getting my dialogue levels set and overall reverbs applied. For a show that requires a mix in the -24db +/-2 range, I usually try to land my overall dialogue level around -25. The dialogue is the anchor of the mix. If I land the dialogue safely in the spec, in most cases the rest of the mix will slot in nice and clean, and my final loudness measurements will be right in the pocket.

I also try to keep in mind my peak limit, especially when mixing sound effects. In action-heavy scenes, it’s easy to crank up the sound elements you want to highlight, but if you aren’t careful you can run up against your limiters and in some cases breach the true peak limit requirement.

When In Doubt, Make it Sound Cool

It may seem like this goes without saying, but if I ever question how to approach a decision or process during my mix, I like to remember this mantra: “Make it sound cool!” Sometimes this means adding that extra bit of reverb on the villainous laugh, or kicking the music up a bit louder than usual for a montage. Other times it means digging in and spending that extra few minutes to really make a scene shine.

One “coolness” opportunity I run into often when mixing is a scene where music and sound effects both have impactful sounds happening. One straightforward way to enhance the coolness is to adjust the sync of the sound effects so they hit right on the beat of the music. It may seem like a subtle change to knock each sound effect out of sync by a few frames, but when the moment hits just right the result makes the whole product feel so much more cohesive and cool.

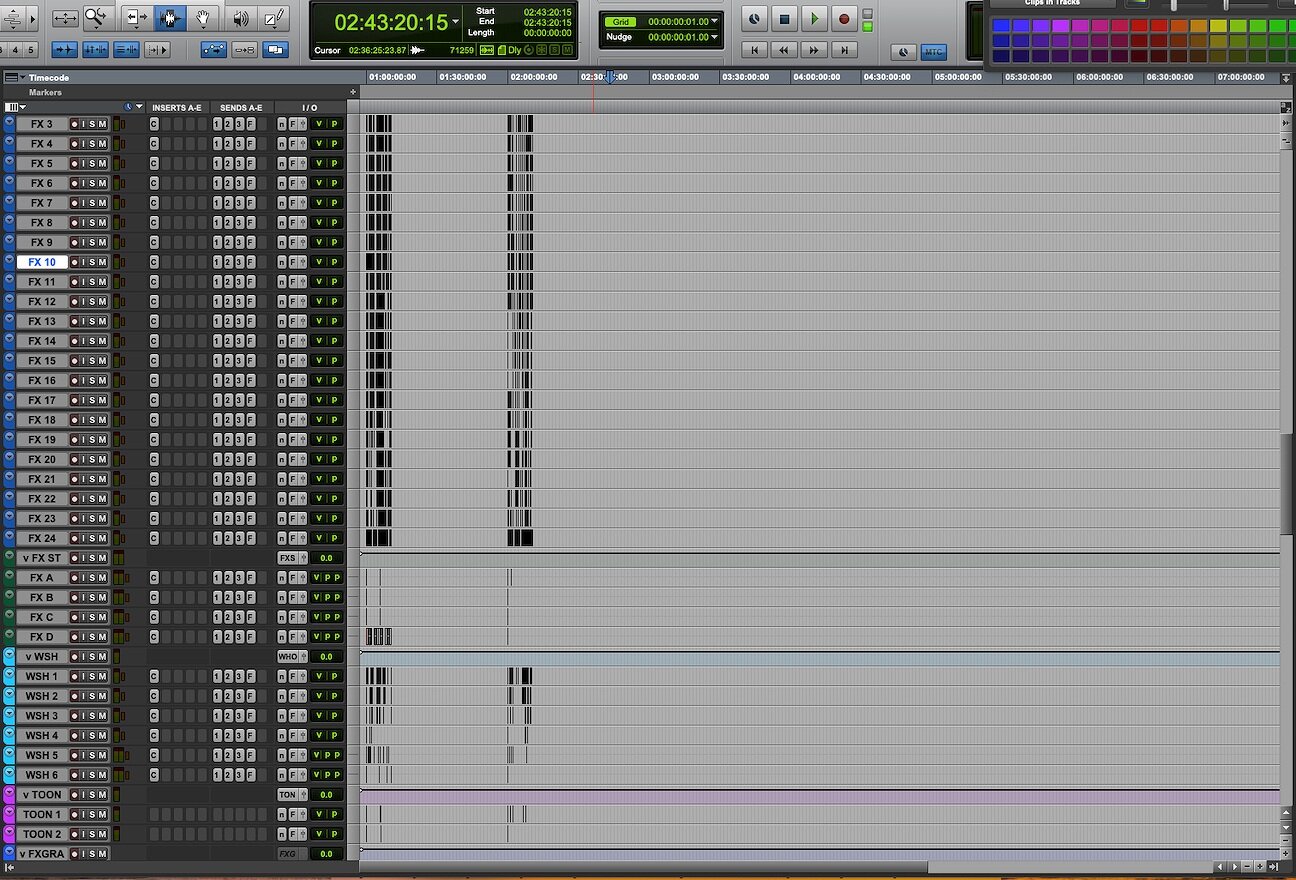

Another fun opportunity is what I think of as “trippy freak-out scenes.” Examples are a character having a nightmare where they are surrounded by floating, laughing heads, or a scene where a character takes powerful drugs which kick in and alter their reality. It’s always worth it to go the extra mile in these moments to really pull the audience into the characters’ wacky world. My favorite tricks in these times are reverse reverbs and lower octave doubles.

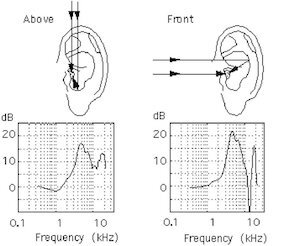

Depiction of ReVibe II plug-in set up for inverted reverb.

I could write a list with many, many items I consider as objectives when mixing. There are so many competing goals and ideas bouncing around in each episode, but I always come back to these three. Working with objectives in my mixing allows me to stay focused on the big picture rather than get sucked into the monotony of following a step-by-step process. For me, it is the key to being creative on demand and ensuring that each mix has a personal touch.