“Each celestial body, in fact each and every atom, produces a particular sound on account of its movement, its rhythm or vibration. All these sounds and vibrations form a universal harmony in which each element while having its own function and character, contributes to the whole.”

— PYTHAGORAS

Christa Giammattei is an audio engineer, sound designer, and musician. She provides both mixing and editing post-production sound services including dialog editing, cleanup, sound mixing, sound design, music editing, and music composition.

While completing several internships, Christa was able to create and mix sound for many top TV shows, documentaries, and advertisements. Now, she freelances those services across the nation while based out of the triangle area of North Carolina. She draws inspiration from her favorite video games and TV shows, which are what originally pushed her to seek out music and sound as a career. Her mission is to create the same sense of wonder and imagination in others that she felt when she first experienced those stories through sound.

She recently created Command + S Apparel was created with one goal in mind: design interesting, wearable clothing for audio engineers and musicians that isn’t just a black tee and “SOUND GUY” written in block print white letters.

How did you first become interested in audio?

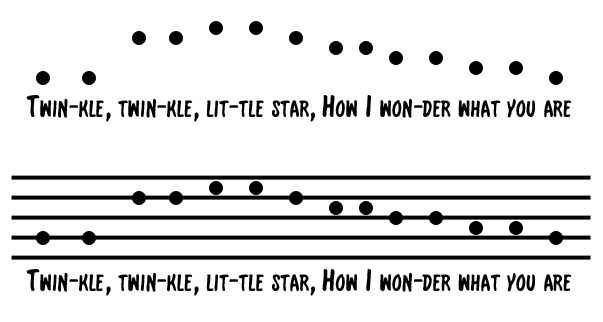

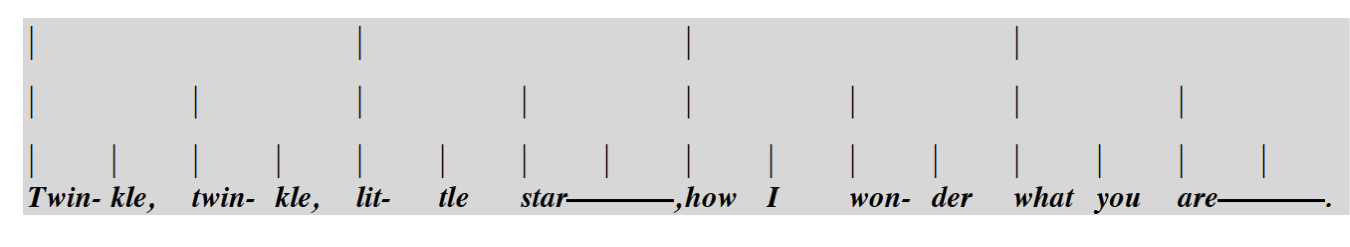

Growing up, I was always fascinated by the sound in movies and video games. I would watch scenes over and over, just listening and appreciating how sound impacted the story. One Christmas, my mom bought me a beginner Yamaha keyboard, and I started to play along with songs I loved and wanted to learn more about. That was sort of the foundation of my interest in audio and music.

What music were you first attracted to as a kid?

This sounds kind of crazy, but I was brought up in a house that very much appreciated some 80’s rock and roll. So, for many years I went through a Journey/Def Leppard phase. Also, of course, lots and lots of video game music. I played tons of Final Fantasy and other rpgs [role playing games], which have a definite classical sound to them. It was a balance in polar opposites.

When did you first think about audio as a career?

I was an avid musician throughout middle and high school (classical percussion and marching band for the win!), but audio engineering never truly clicked in my brain as something I wanted to do until a couple of years into college. I was planning to get a degree in business, but when I stepped away from music after high school, I realized something was missing. I started to Google ‘jobs in music that weren’t teaching or performance.’ Eventually, I stumbled onto music production. I literally had no idea audio engineering was even an option: no one had told me this was a career path that I could take. Once I read about it, there was like this weird inner light bulb that went off; I knew I had found the thing I needed to do. From that moment on, my path was audio engineering, and nothing else.

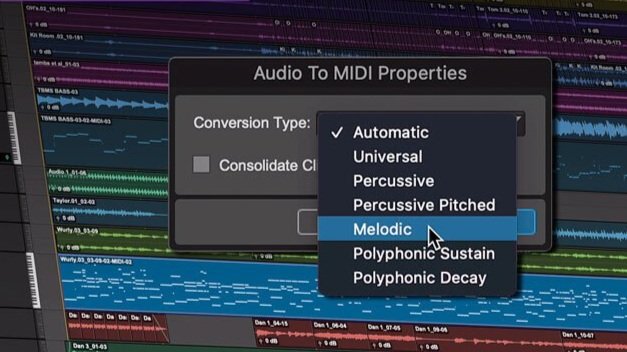

You work a lot in TV and games; how does sound work specifically in these genres?

I always tell people how awesome it is to work in audio post, because you’re helping to tell a story, and that’s really true! When doing sound for TV or a game, it’s all about furthering that overall narrative. In music, there are a lot of different genres: rap, rock and roll, classical, etc. Similarly, in TV and games, there’s a bunch of distinct styles and ways to do things. The sound can make it mysterious, or playful, or upbeat, or gloomy. There are a million possible options, with plenty of room for creativity.

You attended Appalachian State University. How do you feel this program prepared you for your field?

I was incredibly lucky. Not everyone can say that their college experience was worth the money, time, and effort. But mine absolutely was. I had a great professor who pushed everybody to work hard and learn from their mistakes (Shout Out to Scott Wynne at App State!). We had access to multiple recording studios 24/7 and could head in anytime it wasn’t booked to work on our own sessions, class projects, or just fiddle with the equipment. I spent hours sitting at the various desks and preamps and synthesizers just figuring them out. We were also required to pass an audition on the musical instrument we were most proficient on. Having that musical background supporting audio education was enormously advantageous.

The community of musicians and audio engineers I met there was invaluable as well. App State is like the hidden audio gem; alumni have gone on to work on shows like Outlander or at gaming companies like Epic Games. So, there’s a great network of us that can ask for advice or help when we need it.

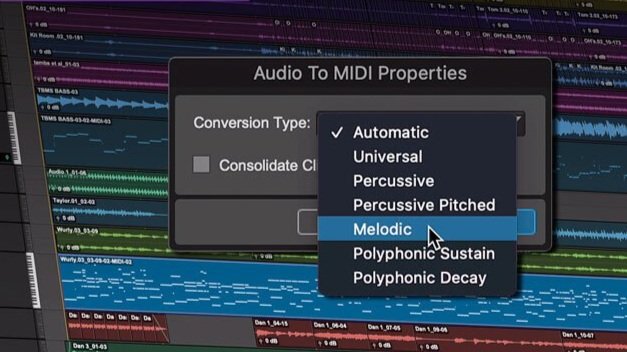

What gear do you currently use? Any favorite pieces?

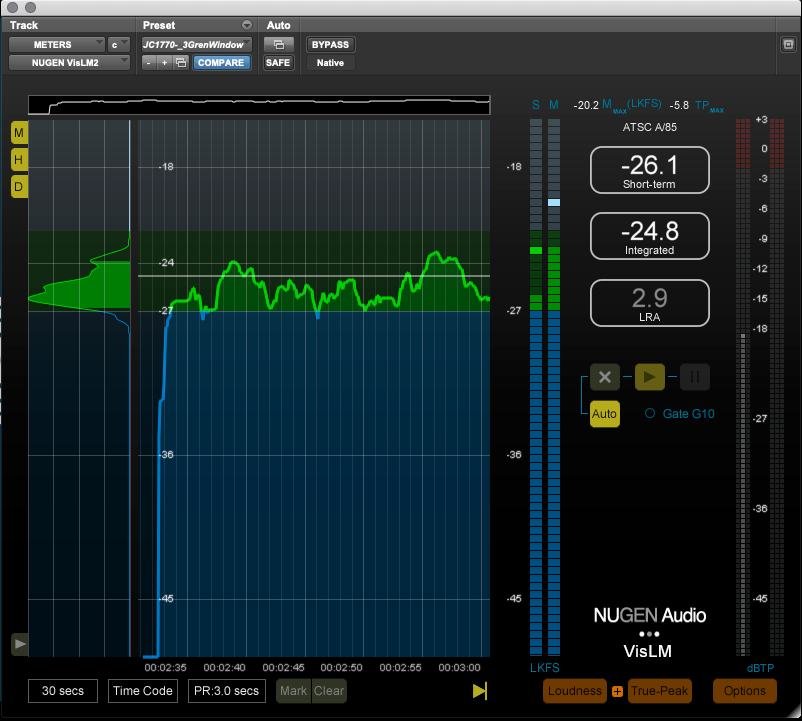

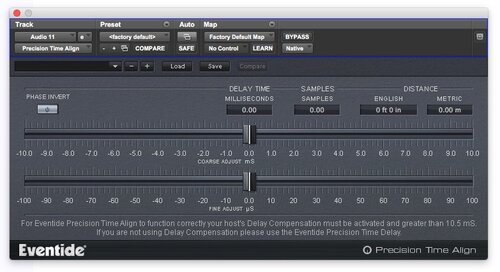

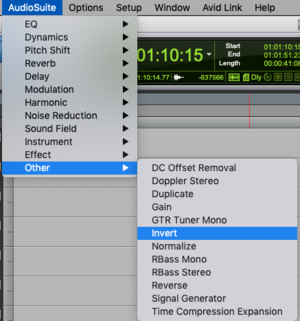

Most of my gear is “in the box,” since I work in post. Izotope RX7 advanced is my saving grace and the best $800 I have ever spent. I use it on every single session I work on, without fail. Dialog Isolate, De-Rustle, and De-Reverb have saved many a zoom recording this year for me, and I honestly don’t think my workflow would be complete without it. Recently I have been loving Oeksound’s Soothe 2, and also the API-2500. I have this really specific Yamaha piano that I adore called the P-115 as well.

Have you ever experienced any sexism as a woman in the industry?

Oh, absolutely. I could probably write an entire saga of instances where I’ve experienced sexism in the industry. “Where’s the sound guy?” is my personal favorite (haha). Over time, I’ve learned who to work with and who to avoid, so it’s definitely gotten better. I think women have to create a harder shell for comments to bounce off of in the audio field, and a stronger technical foundation to stand on. The worst experiences involving sexism for me were the more subtle ones- situations where I noticed I was being treated very differently in the workplace by people I thought I respected. It took a long time for me to understand that certain behaviors were not acceptable and to stick up for myself. But I’ve made it part of my personal goal to make it known that women are here in this field, we are growing, and we’re damn good at audio.

Your apparel CMD + S seeks to redefine apparel in the audio field that usually depicts stereotypical gendered images on it. As you say on your website: the aim of CMD +S is “[…] to design interesting, wearable clothing for audio engineers and musicians that isn’t just a black tee and ‘SOUND GUY’ written in block print white letters.” What inspired you to manifest your feelings about such apparel into your own clothing line? How has the journey been?

I wanted to buy myself an audio shirt one day and searched sound engineering t-shirts online. I browsed for hours, trying to find any clothing that an audio engineer would want to wear. There was this growing sense of disbelief as I saw there were maybe 20 versions of very similar tees, and most of them had some iteration of sound guy or sound dude or something like that. I was like “Is there not one single shirt that a woman could wear?!” And not only that, even the sound guy shirts were so generic and non-inclusive. It was embarrassing. And just another small example of how womxn are so often excluded in this industry. I realized there was a market here that was missing- there are millions of people out there who love sound and music, either for their career or just a hobby or casual interest. The more I thought about apparel for audio engineers, I realized I had ideas for designs that could be worn by anyone in the industry, regardless of gender, and inclusive for everyone.

It’s been a learning experience for sure, so far. Having to figure out websites, shipping, pricing, wholesale, social media, and everything else has been a challenge. But every person who buys a shirt is one more person that I know feels like I do. Even though I just started Command +S Apparel this year, it already means so much to me. It’s helped me network with people I never would have otherwise, and I can’t wait to keep going.

I love the myth and was elated to see her hair have cables. Her story is often misunderstood, I think, in that she was punished for a sexual assault and turned into a monster whose eyes could turn man to stone, with snakes as hair. Perseus beheaded her, popular with the Perseus movies lately. To reclaim this image in a field that is dominated by men was just incredible to see; I bought a shirt right away. How did you pick Medusa for the icon on one of your CMD + S shirts?

THANK YOU. Yes, I totally agree. Parallel to what you said, I was reading an article about how the story of Medusa is misunderstood; that she wasn’t a monster and was instead punished for being a powerful woman. The story stuck in my brain, and as the idea for Command +S started to form, the snakes in her hair turned to cables in my mind. I decided we needed some more powerful women on shirts, and knew that I needed to include her, but in all her audio glory.

What’s the difference between working in sound for music and working in sound for TV?

In music, the audio production is (obviously) the core focus, but in post, sound is more of a supporting act. That’s really the key difference. I’ve heard a lot of people in post-production say that if the audience doesn’t notice the sound then you did a good job. What they mean is that if the audience leaves that experience remembering the story and the characters and the emotion behind it, and not like “Oh, that one song,” or “Yeah that explosion was something,” then you did what you set out to do. You supported the narrative, whatever that was, and that’s what it’s all about.

Do you approach sound for TV and film documentaries differently?

I think I approach sound for documentaries as a whole pretty differently than say, a commercial or something based on fiction. Docs tend to be more reflective and linear, mostly because you are telling a very real story of someone’s life. It’s important to them, and so I try to honor the vision that is presented to me and uplift it the best I can. I don’t use quite as many unconventional effects, and I focus more on the dialog to make it as upfront as possible.

If you could talk to yourself from ten years ago, what one piece of advice would you tell yourself?

Don’t be afraid to experiment and jump outside of your comfort zone. That’s how you’re going to find your own unique sound, and that’s what’s going to make you stand out. Stay true to yourself, remain humble and willing to learn. Arrogance doesn’t get you super far in audio, and people will eventually recognize the individuals who work hard, support their friends, and love the industry.

Thank you for your time!

Thank you so much for having me!

Follow Christa/CMD+S Apparel

Instagram @cgiammatteisound @command_s_apparel

Facebook @commandsapparel

Twitter @izzy_marizee