Ever wonder about the strange noises that electronics make? Capturing that weird and turning it into music or art? Welcome to the world of circuit bending, where consumer gadgets are hacked into one-of-a-kind synthesizers. Officially circuit bending has been around for as long as circuits have existed. However, the popularity of coaxing music from frankensteined electronics paralleled the rise of synthesizers in the 1960s. Reed Ghazala’s name pops up in 1966, when he coined the term, as the leading figure in the movement. He has written about (Circuit-Bending: Build Your Own Alien Instruments, 2005) and taught techniques for circuit bending, and his builds have been made it on recordings by artists such as Tom Waits, and The Rolling Stones. Circuit bending is a chance art form. It relies on imperfections and momentary occurrences or happy accidents.

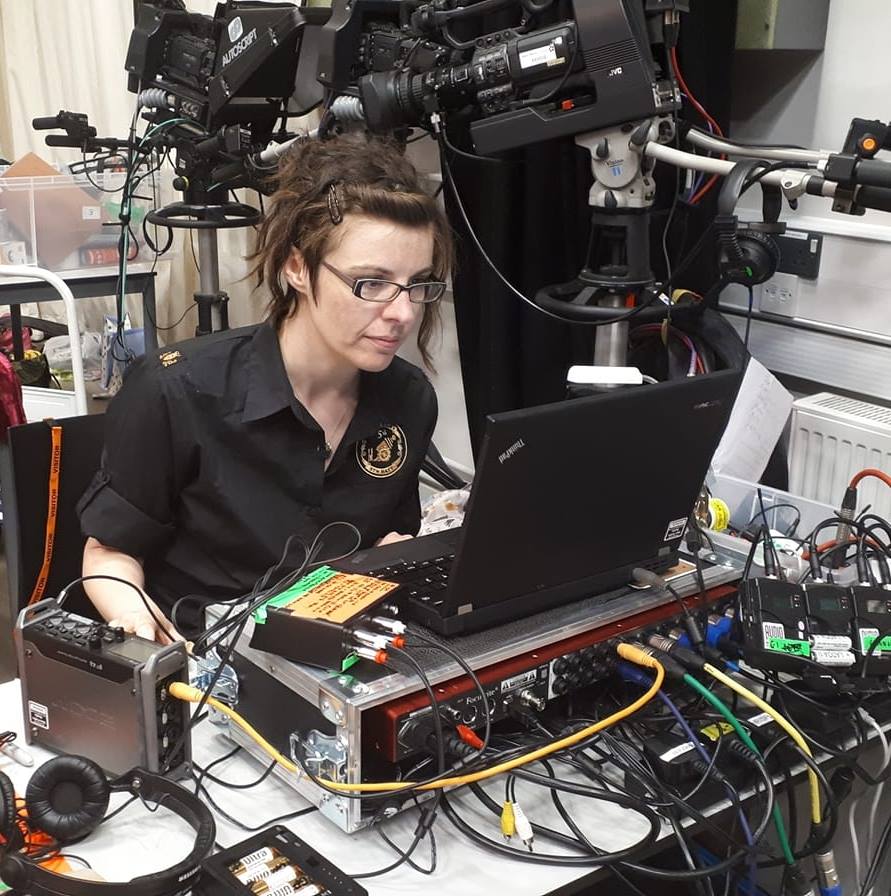

In order to learn more about circuit bending, I interviewed Chris Bullock, a location sound recordist who also makes music as Bone Music.

What got you into synths? And what led you into Circuit Bending/Circuit Modding?

I was working for a YouTube channel and the main talent asked if I had any use for a small synth he’d been given as a thank you for helping out on a crowdfunder. It turned out to be a Korg Monotribe, which is a gorgeous small monophonic analogue synth. I was doing a sound production module at a local college and started using it in some sound design elements for that. I found it really satisfying, there’s a meditative quality to making a synth drone, which appealed to my sensory-seeking nature. I’m autistic so playing with drones while watching a lava lamp is relaxing on another level! Ultimately, there are some limitations like the Monotribe doesn’t play unless you press a key. I ended up doing weird things like keeping it playing with my foot while using my hands to make other sounds, so I started looking at more flexible synths.

My first mod was to add MIDI capability to the Monotribe. It’s an easy thing to do, no soldering required, but it reminded me how much I used to love building electronics kits as a kid. So I started to learn electronics again, this time with a focus on music and an intention to better understand what I was doing. I also got into watching Look Mum No Computer (LMNC) videos on YouTube and really enjoyed his weirdness and enthusiasm for building strange instruments.

What is Circuit Bending?

Circuit bending is manipulating a circuit to get an output that wasn’t intended by the manufacturer, like a new interesting sound. You can do this by making new connections on the circuit board using wire or even your fingers. It’s really important to only use battery-operated toys and stay away from stages that have large electrolytic capacitors, which can store a lot of charge. Often bends will be things like freezing or crashing a chip momentarily, or slowing down the signal coming from a clock source. Everything sounds better slower!

How do you approach a new project?

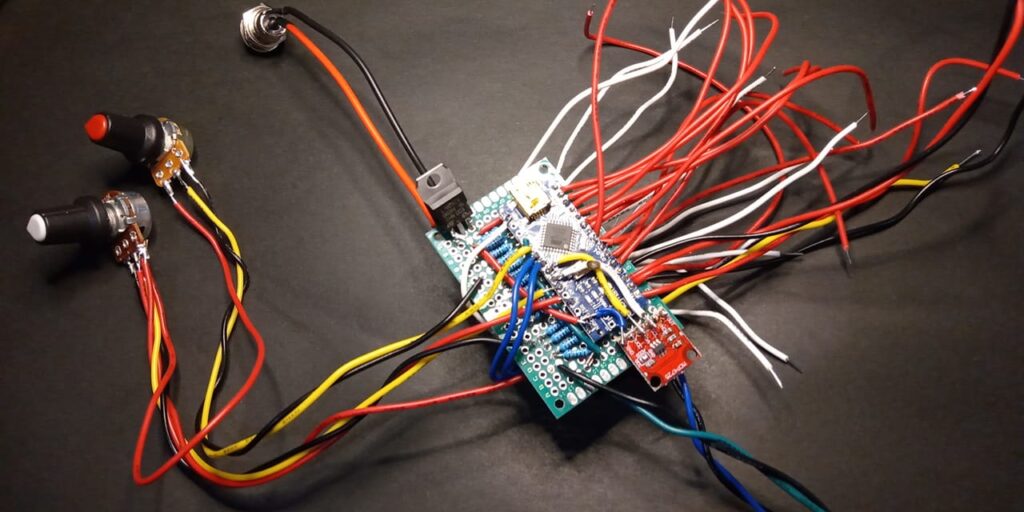

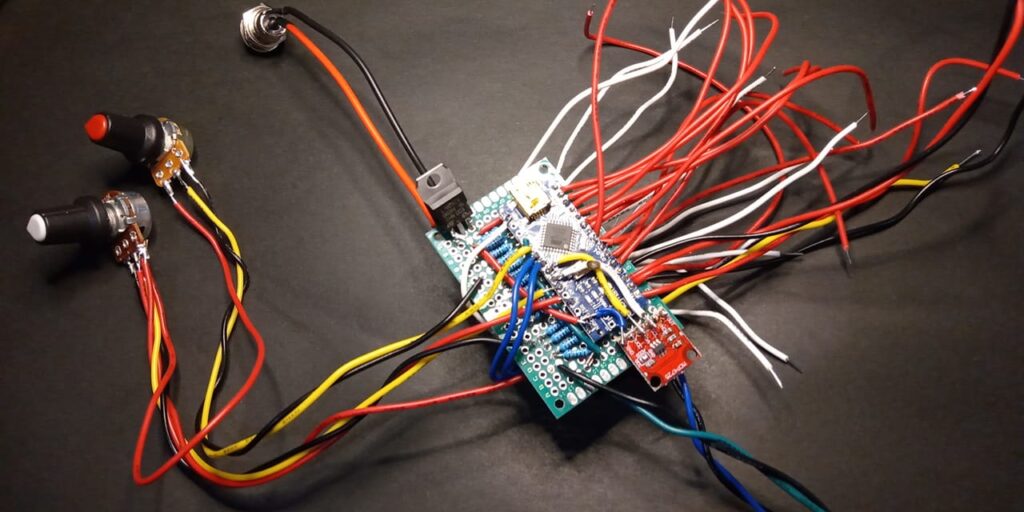

When I start a new project, I have a look around online to see how other people are approaching the same idea. Right now, I need to make some oscillators for my synth and I’m weighing up the options like whether to make something Arduino-based or to stay analogue. There are so many ways to do a similar thing, all with different pros and cons. What I’ll do is test a few ideas out on a breadboard before I build anything. Reading comments under YouTube videos and on forums helps with ideas, particularly when things don’t work how you’d expect.

Where do you get your inspiration?

My successes are built on other people’s experiments, I have to acknowledge that. But I also get a lot of inspiration from my environment. Every time I learn something new I’m wondering ‘will it noise?’ I learned about how inductors and capacitors can be made to resonate and my immediate thought was could you make some sort of one-shot reverberation based on this? I haven’t answered that yet. I pulled an ultrasonic range finder out of my Arduino box of bits the other day and thought Theramin! It’s not just electronics, I’m always listening to things in the kitchen or out on the street, good noises are everywhere.

I used to work with seismic data and I’ve thought about making an installation piece that uses a representation of the frequency content of layers in the earth to make music, but as we go deeper we generally just attenuate high frequencies. It’s difficult to make something geologically valid and sonically interesting. I’ll probably come back to that in the future.

What is your favorite piece of gear/favorite project?

It’s a small thing, but I made a version of the Smash Drive, which is a distortion pedal built around an LM386 amplifier chip. It’s one of the first things I got to work on stripboard, so it was rewarding having success after a few failures. I made it inside an Altoids tin. It’s silly, but I’ve always associated those tins with hobby electronics builds. I had a long-standing dream to make an electronics project in an Altoids tin.

Tell me about the Koko/Furby Project.

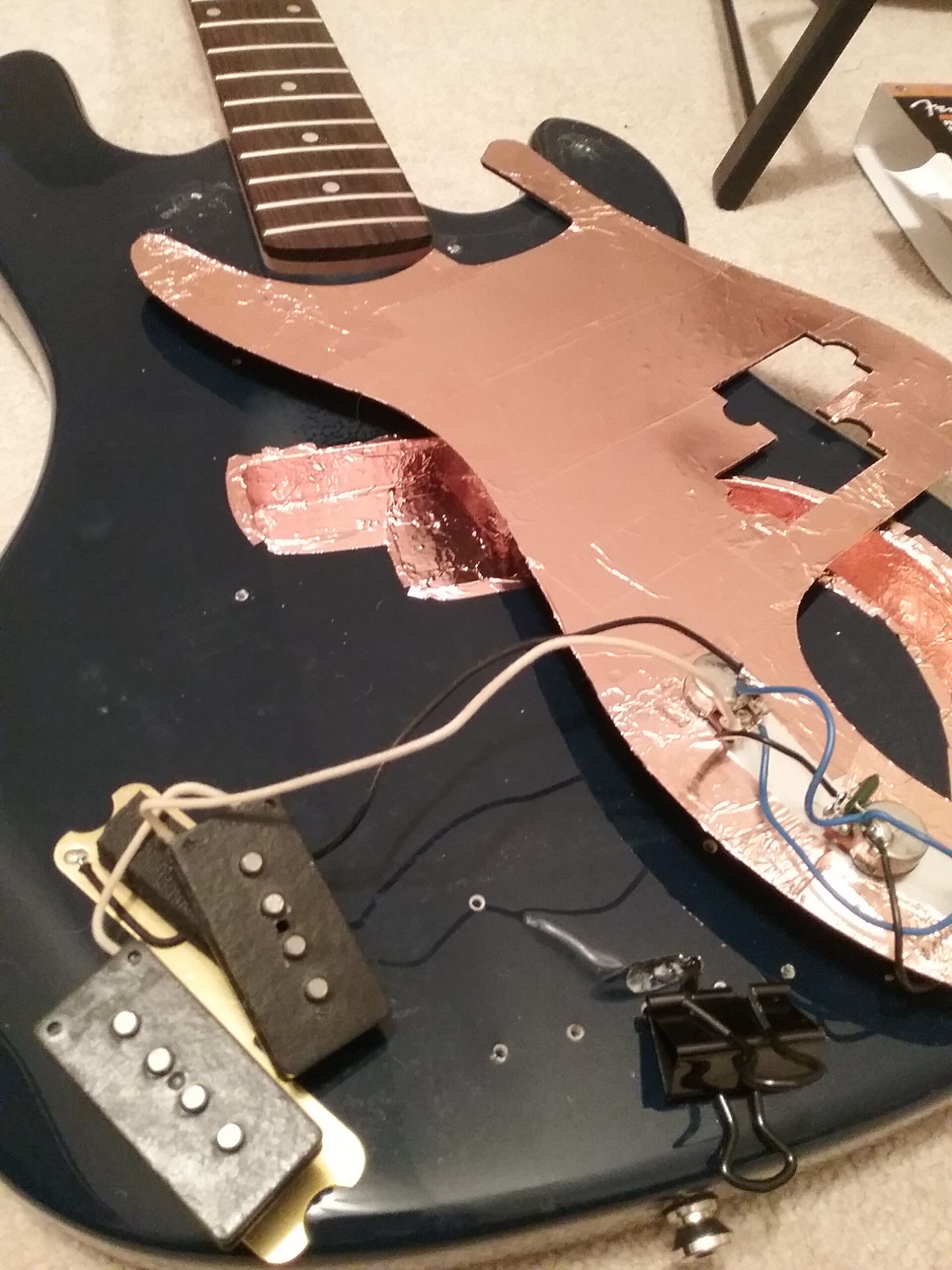

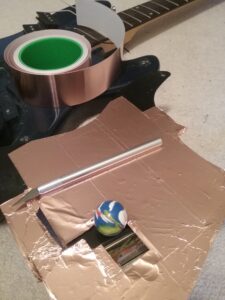

Furbies are a popular toy to bend, although not that easy. I was looking on eBay and saw this Furby that needed TLC. He was dormant, hadn’t started up in a long time. I felt weirdly sorry for him, so bought him. I did some research and discovered you can kick-start Furbies by spinning their motors. I had to disconnect the battery compartment because it was so corroded, but when I attached a new battery pack and kick-started it, eventually he woke up and told me his name was Koko. He’s sleepy and stubborn, but I’m very fond of him. I put switches in his ears so you can squeeze them to make connections between points on his circuit board that make him stutter or crash. I tried to slow him down by replacing his crystal resonator with an adjustable high precision oscillator, but unfortunately, he doesn’t speak in deep demon-like tones when you do that, he just says his phrases really slowly. He’s given me a few scares, a fair bit of frustration, and a small fire but I seem to have developed some sort of weird attachment to him. I put an audio jack in him and grabbed a load of samples I use in other projects.

How does failure play into your process?

I fail all the time, I try to make things where I haven’t quite understood the entirety of how something operates or interacts with other parts, and so it doesn’t work. I actually have a bag I called the ‘bag of shame’ because it’s full of little dead circuit boards. I’m waiting for a particularly aesthetic chutney jar in my fridge to be empty because I’m making an art project called ‘we are lit by the light of our failures.’ It’s going to have some soothing colour changing LEDs running off an Arduino and a bunch of my non-functioning circuit boards in the jar. Sometimes all you get is a lot of frustration, but often you learn something useful by failing. Other times you end up with the basis of a slightly pretentious art project.

What advice do you have for someone just starting out?

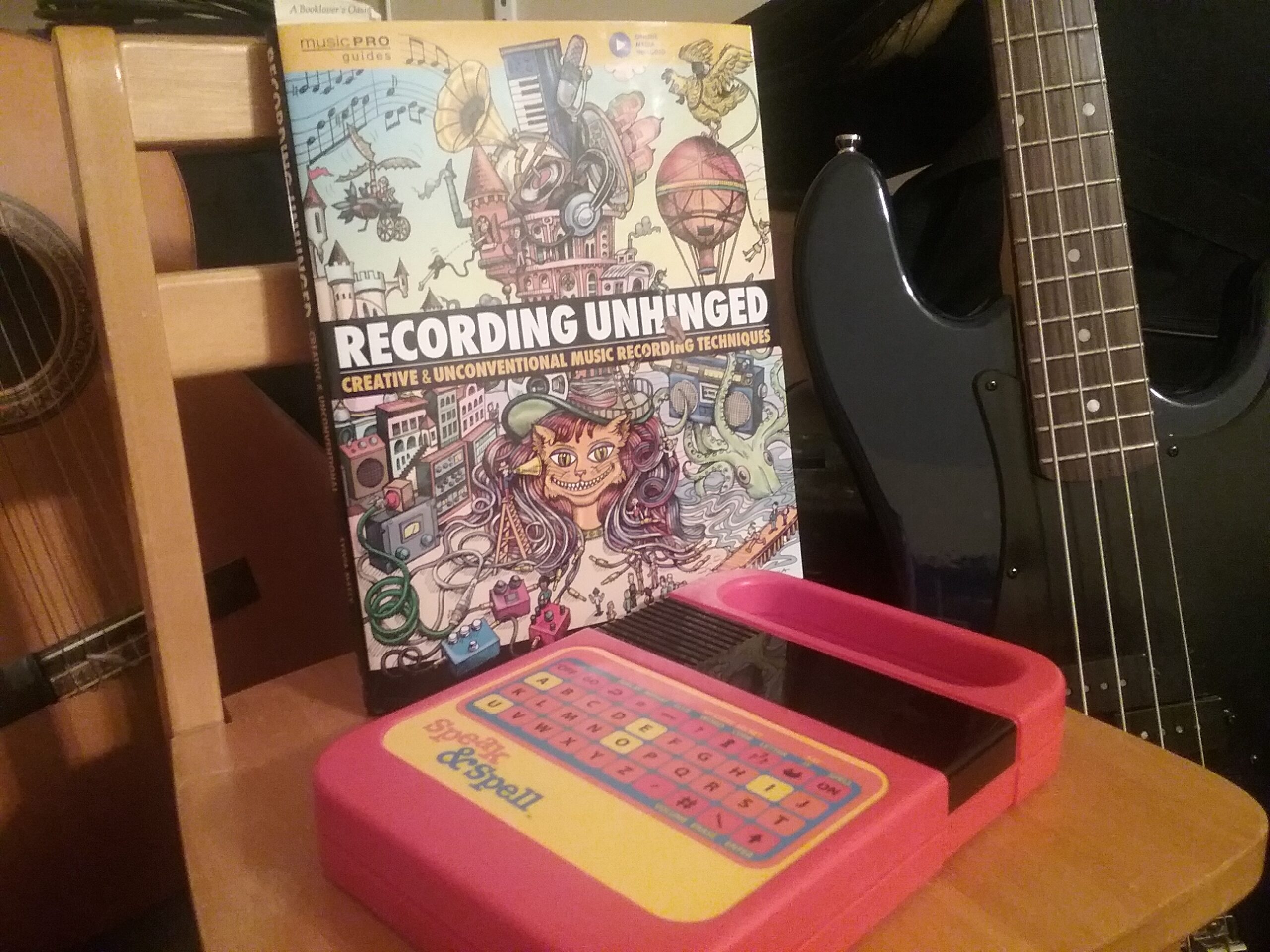

Don’t be afraid to fail, but start small. If you have ideas for big things, write them down to get them out of your head for a bit and try a few small things first. Kit builds are good. If you are looking for toys to bend, look for older ones with discrete components where you can identify things like the processor, clock source, and memory. Look for information on YouTube and find a community of makers. Books are good – Hand-Made Electronic Music is inspirational. Get a decent soldering iron, don’t open up anything mains powered or with a flashgun or CRT, and don’t forget to ask of everything ‘will it noise?’

Chris Bullock’s YouTube Channel https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJtuQavcjxMAce8t17MEQNg