Strategies and a Suggested Standard Operating Procedure for Soundcheck

Welcome to Part Two! For a monitor engineer, consistency is key in making sure musicians always have great-sounding mixes, smooth communication, and awesome performances. Let’s explore a solid method for dialing in perfect mixes and living your best life in monitor-world

Part One

Before the Band Arrives

Recall your start scene.

Use pink noise to check that all monitors are functioning, set, labelled, and positioned as intended. Do this for your cue wedge too, which ideally matches the stage monitors for consistent referencing. Confirm your talkback system works to both stage and FOH. Do a line check to make sure the patch is correct and noise-free. Confirm every input is showing up at a reasonable level and troubleshoot anything that’s not.

Zero out the mix sends.

Start with a clean slate for each performer’s mix by making sure no input channels, other than talkback from FOH and MON, are being sent to the mixes. Check that aux or bus sends are activated and outputting properly for the room. Decide on pre – or post-fader per channel or mix and be extra mindful of which ones are post-fader, as fader moves will affect the artist’s mix. This can be useful, for example you can mute problematic channels quickly and catch the nuances of solos. If the band’s rider states what is desired in their IEM mixes a good starting point is 0 dB for vocals, -10 dB for instruments, and less for everything else.

Confirm the stage plot and input list with the band or manager.

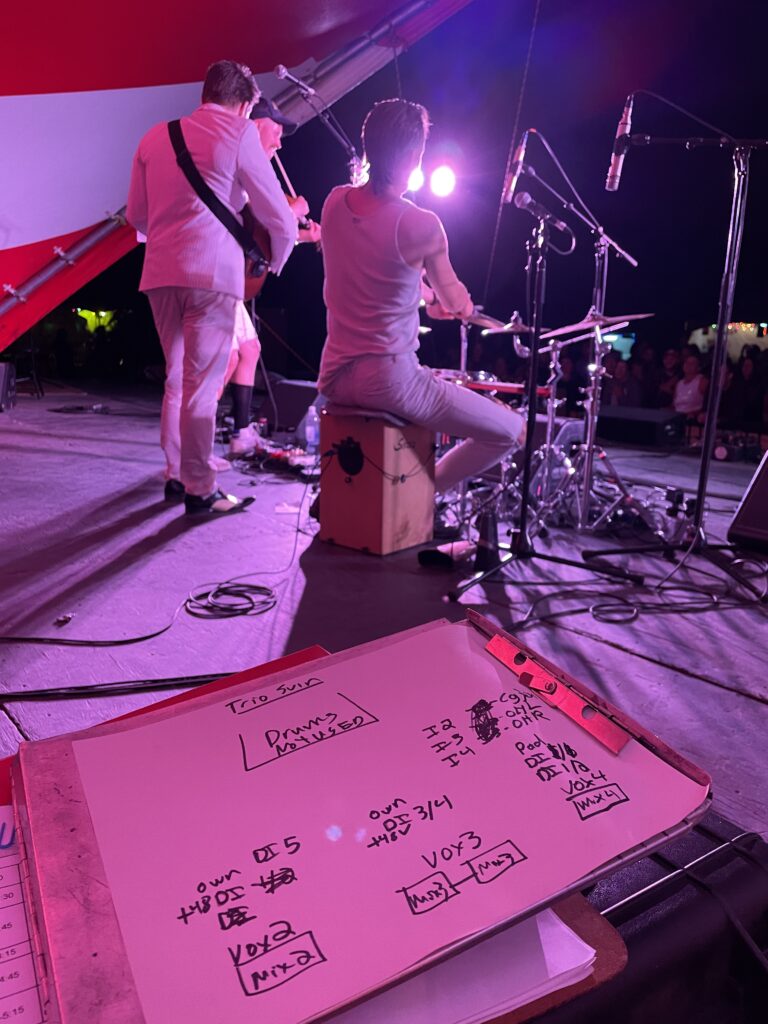

Update the stage team and FOH if anything’s changed and adjust your start scene accordingly. At festivals, a clipboard or whiteboard you can draw the stage plot, input list, and monitor mixes on can be helpful.

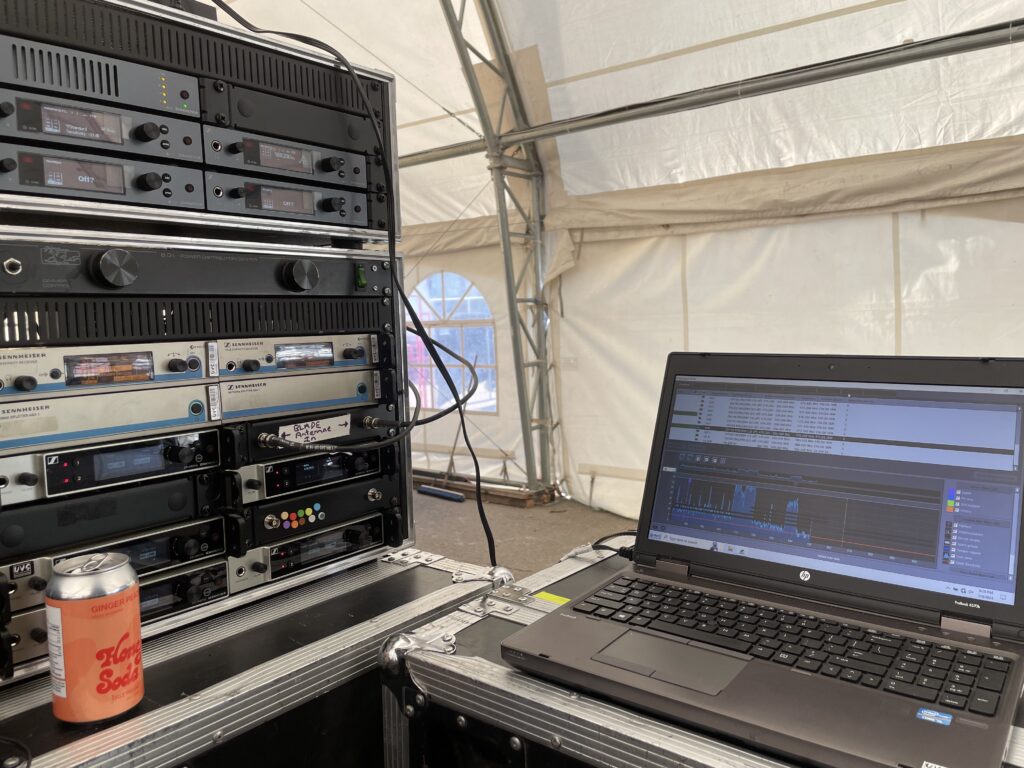

Add wireless and IEM channels to your software.

Once the input list is validated, add any wireless and IEM channels into your coordination software (e.g., Wireless Workbench or Wireless Systems Manager). Always have a few backup frequencies ready in case of interference.

Do a wireless frequency scan.

Conduct a scan (as discussed in Part One: Ringing It Out) to check for any RF interference in the venue. Use your system’s scanner to identify the clearest frequencies and update the wireless system accordingly making sure all transmitters are synced and ready to go. If you don’t have a dedicated RF tech, make sure to continuously monitor RF levels pre-show and during the show and be ready to swap gear or channels if needed. If interference arises after the scan, assess whether it can be addressed within the changeover time. Sometimes you may need to prioritize getting the stage workable.

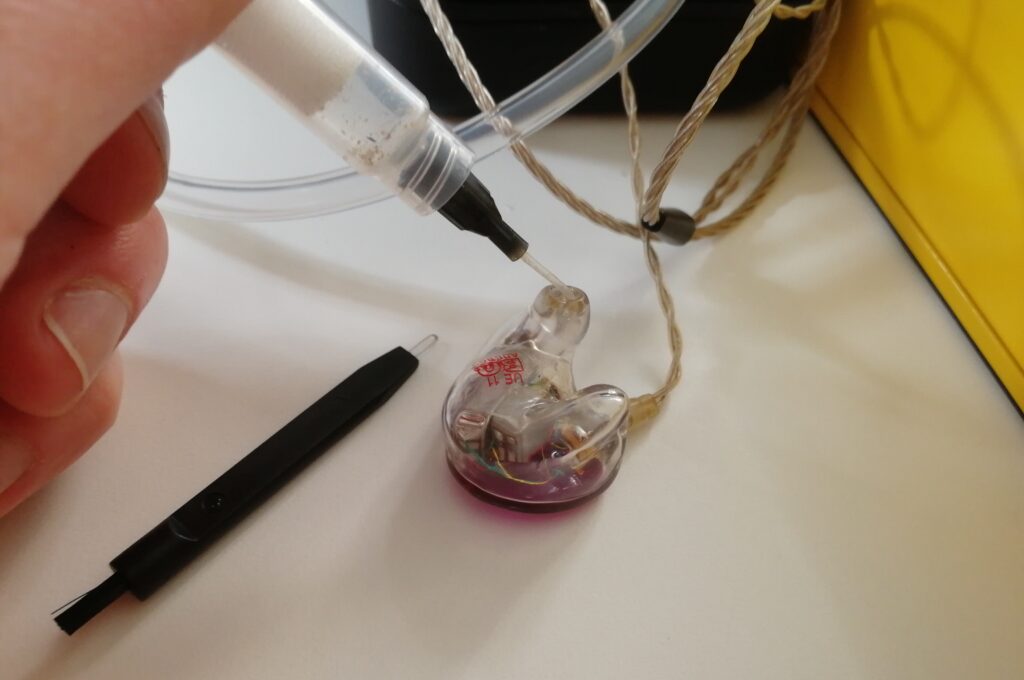

Be Careful with In-Ear Monitoring (IEMs)

- Avoid sudden moves on the mix, those sends go directly to the artist’s ears. Make small, deliberate adjustments. Hearing health is a priority for all of us, and I strongly advocate for investing in custom musician’s plugs.

- This should go without saying, but: NO hot patching and don’t drop mics. Pay attention to the details. Be gentle, because everything matters.

- Consider inserting a limiter on IEM outputs as an additional safeguard.

- Monitor these mixes using IEMs yourself, ideally the same brand/model the artist is using, or a neutral reference IEM with similar isolation and response.

- Some vocalists may notice latency due to the lack of vibrotactile feedback with IEMs. An analog vocal path can help reduce this perceptual disconnect.

- Audience mics on the sides of the stage, lightly fed into IEMs can help the band feel less isolated and more connected to the crowd.

Soundcheck Process

Introduce yourself:

Use the talkback mic, make eye contact, and confirm the band can hear you. Use mnemonics or other memory activating techniques, like the method of Loc, or simply writing down names, to remember as best you can the band members’ names. Remembering names is a soft skill that speaks volumes, it shows respect, builds rapport, and reinforces all the hard skills you’ve worked so hard to develop over the years.

Start with vocals:

Most performers rely on vocals as their main reference. Getting this right first helps everyone feel grounded; it’s essential for communication and is often the loudest input requested in monitor mixes. That said, some bands or FOH techs may prefer to start with channel one, usually the kick drum, you can always just ask and check what works best for the team, but I would default to vocals first and then moving on to the rhythm section.

Guide the band through the check:

- Set gain, HPF, phase, and EQ per input (you may even be able to get a rough starting point of these settings before the band arrives with your input list).

- Bring each input up in the performer’s mix first, then distribute to others as needed.

- Suggest and agree on signals the band can use if they need adjustments during the show.

- Ask the band if they want any effects in the monitors, sometimes a little reverb on the vocals is superb.

- If working solo, consider using a tablet or iPad connected to the console to make quick on-stage adjustments without needing to run back and forth. Being able to adjust mixes in real-time while standing next to the performer and listening to their mix can be faster and more personal than using the talkback.

- Avoid maxing out sends and keep space in your mix. Try subtractive mixing -if an input really needs to cut through, lower other channels to find the requested balance, carve spectral space with EQ, and adjust panning. Don’t just push it louder, plan each mix intentionally.

Some Tips on Handling Feedback Before reaching for the EQ

- Reposition the monitor

- Try flipping the phase on DI’s and vocal mics positioned very close together to check for phase issues. Listen to what sounds better to you and go with the one that feels right.

- If time’s short, pull the level down and ring it out later.

- Again, listen to the wedges! Once the band is playing, walk the stage if possible. Listen from their perspective and verify placement and angles.

- Need help identifying frequencies? Tools like SMAART or Open Sound Meter can quickly verify what your ears are telling you.

Always Remember

- “Don’t take things personally!” What Does a Monitor Engineer Do?

Leveraging Technology on Stage

Using a tablet like an iPad connected to the console can streamline soundcheck and save you a lot of literal steps. Just make sure you’re on the right Wi-Fi network/subnet and enter the correct IP address from your console. Additionally, some systems, such as Klang, allow musicians to control their own monitor mixes their own device. If the band is comfortable with this, it can empower performers to punch in their own preferences. Let them know you are there to assist, adjust settings, and even teach them how to use software whenever needed. Remember, making them feel confident and comfortable is the priority. Even if the band is self-mixing, check in to make sure their devices are connected properly and that they know how to use the system.

Final Touches Before the Set

- Verify settings, confirming levels and routing.

- Walk the stage and listen again!

- Ask about cues or changes.

- Confirm everyone in the band can are happy with their mix and are show ready.

- Use a graphic EQ to tame feedback.

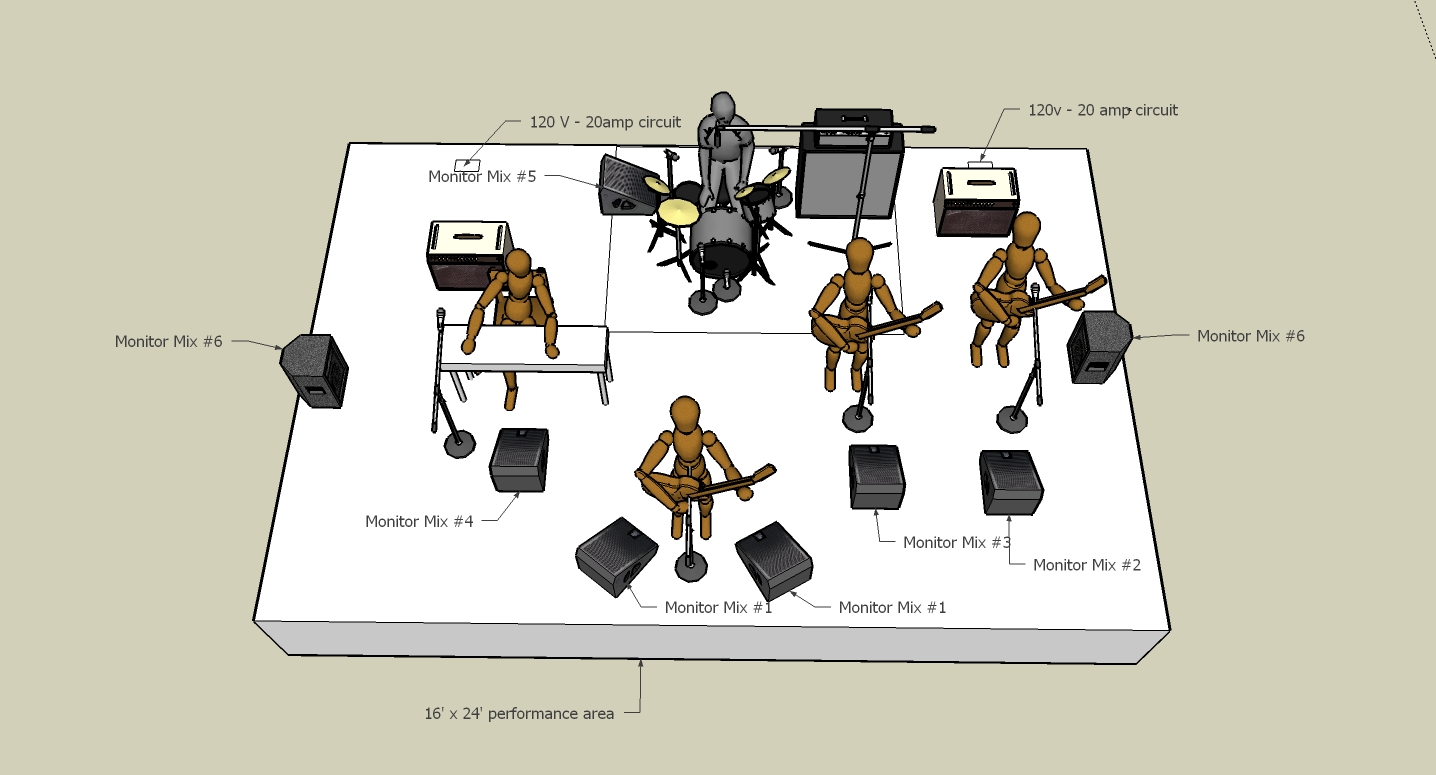

- Spike the stage with color-coded tape outlining monitor placements and equipment positions.

- Safe any channels that won’t change between acts, for example MC mics.

- Save your scene! Be careful when recalling scenes!

- Double-check vocal mics and monitor mixes

When the Show Starts

- “Look up!” The Sound Engineer Is the Conduit2

- Stay sharp, monitor world doesn’t end after soundcheck. Stay focused and ready for real-time adjustment.

- Amplify the artist’s energy and the entire space will resonate with them.

By following these strategies and suggested operating procedures you’ll be able to deliver a smooth, personalized soundcheck experience that supports the performers and keeps you loving life in monitor world. Stay consistent, be proactive, communicate clearly with artists and crew. Keep on gigging and don’t forget to giggle sometimes.

I love references and cite it out when in doubt!

Check out these two fantastic articles by Michelle Sabolchick Pettinato, one of the OG SoundGirls. Her wisdom on live music mixing continues to inspire and guide generations of engineers.

While you’re at it, dive into the psychology of mixing monitors by Becky Pell—a must-read for anyone serious about understanding the human side of sound.

Reference links:

1https://www.mixingmusiclive.com/blog/what-does-a-monitor-engineer-do

2https://www.mixingmusiclive.com/blog/the-sound-engineer-is-the-conduit

Additional Resources:

https://www.rationalacoustics.com/pages/smaart-home

https://opensoundmeter.com/en/

https://soundgirls.org/ringing-it-out/

https://www.prosoundweb.com/different-strokes-mixing-monitors-for-disparate-personality-types/