Read English Version Here

A Brasileira Adriana Viana trabalha como diretora técnica, e técnica de PA e monitor freelance. Situada em São Paulo, já trabalhou com diferentes artistas da música Brasileira, como Teatro Mágico, Flora Matos, Plutão Já Foi Planeta, Rodrigo Teaser – Tributo ao Rei do Pop, e mixou shows de artistas internacionais no Brasil, incluindo Mark Lanegan, a banda jamaicana Toots and the Maytals e o guitarrista de blues Jimmy Burns. Atualmente está em turnê com uma das maiores compositoras brasileiras, Adriana Calcanhoto além de operar o PA das bandas Far From Alaska e Rashid. Ela também assina a direção técnica do Women’s Music Event, onde monta uma equipe de mulheres qualificadas para operar toda parte de audio do evento.

Quem vê Adriana operando uma mesa de som pode ter a impressão de que ela passou a vida inteira mixando. Mas quando ela começou a trabalhar na área há 12 anos, ela não tinha autorização para mexer no equipamento de áudio. Adriana sempre teve interesse pelo audio ao vivo – não apenas ia aos shows, mas também acompanhava seus amigos nas montagens e nas passagens de som. “Eu pensava, o que esse cara faz? Ah ele arruma o som… eu já entendia a profissão, sabia que tinha um cara que montava, um cara que fazia o som, um cara que fazia a luz, e achava super interessante.”

Quando soube que haviam duas vagas em uma locadora de equipamento de áudio, ela foi fazer uma entrevista no intuito de entrar no mercado, entender melhor a profissão e aprender.

Chegando lá, descobriu que as duas opções eram: recepcionista ou almoxarife. “Eu falei que queria ficar no almoxarifado! Me perguntaram se eu tinha experiência, eu falei que não, mas que era muito organizada e queria aprender para entrar no ramo.

Eles precisavam de alguém que conferisse tudo que tinha lá, contar cada coisinha. Então quando vinha um técnico, eu perguntava: o que é isso? ‘É um Shure SM58’. Esse outro também? ‘Não esse é um beta 58’. E aí eu fiz a contagem, deixei tudo organizado, dava entrada e saída nos gaveteiros.” Todos enfrentam dificuldades ao começarem uma carreira no áudio, mas Adriana aponta que mulheres ainda têm uma dificuldade extra que é enfrentar assédio e machismo. Adriana não foi ensinada sobre a parte técnica, e como solução para aprender, ela lia todos os manuais que encontrava. Sem apoio na empresa onde trabalhava e sem dinheiro pra fazer um curso de iniciação ao áudio, comprou um livro de fundamentos básicos do áudio e começou a estudar. “Eu ia aprendendo do jeito que eu podia, pegava apostila, livro, ia lendo o que eu encontrava. Eu ia acompanhando nos eventos e ficava observando.”

Um dia, em um dos eventos que Adriana costumava acompanhar, um técnico freelance percebeu seu interesse em aprender e convidou-a para acompanhar seu trabalho em uma casa de show “nos sábados, às 14h. Ele não operava, ele era roadie de palco, fazia todo cabeamento, patch, monitor, e tudo que ele sabia ali ele me ensinou. Ele falava, ‘isso é um XLR, isso é um P10, isso é um multicabo’. Ele me passou a visão geral do sistema, as conexões e eu fui aprendendo. Eu trabalhava de segunda a sexta na empresa de som, e todo sábado por meses eu ia de graça pra aprender. Cabeava, microfonava, ligava os monitores, AC, ficava na house vendo o técnico operar. Só olhando. Quando sentia uma brecha, eu perguntava.” Logo, o técnico que ensinou Adriana precisou de sub – e quem melhor para substituí-lo do que a pessoa que ele treinou? “Eu comecei a trabalhar como técnica de montagem de palco e logo eu comecei a operar, depois entrei no Centro Cultural São Paulo e fiquei fixa no setor do som. Aí comecei a trabalhar em várias empresas de som, fazer muito show. Eu sempre saí para trabalhar e aprender, eu lia manuais, não tinha dinheiro pra fazer IAV, nunca fiz, então eu lia apostilas. Tinham pessoas que me ensinaram algumas coisas, eu pude acompanhar grandes técnicos trabalhando, então você vai absorvendo. Mas foi muito na cabeçada também, de meter a mão e ir pra cima.”

Um dia, em um dos eventos que Adriana costumava acompanhar, um técnico freelance percebeu seu interesse em aprender e convidou-a para acompanhar seu trabalho em uma casa de show “nos sábados, às 14h. Ele não operava, ele era roadie de palco, fazia todo cabeamento, patch, monitor, e tudo que ele sabia ali ele me ensinou. Ele falava, ‘isso é um XLR, isso é um P10, isso é um multicabo’. Ele me passou a visão geral do sistema, as conexões e eu fui aprendendo. Eu trabalhava de segunda a sexta na empresa de som, e todo sábado por meses eu ia de graça pra aprender. Cabeava, microfonava, ligava os monitores, AC, ficava na house vendo o técnico operar. Só olhando. Quando sentia uma brecha, eu perguntava.” Logo, o técnico que ensinou Adriana precisou de sub – e quem melhor para substituí-lo do que a pessoa que ele treinou? “Eu comecei a trabalhar como técnica de montagem de palco e logo eu comecei a operar, depois entrei no Centro Cultural São Paulo e fiquei fixa no setor do som. Aí comecei a trabalhar em várias empresas de som, fazer muito show. Eu sempre saí para trabalhar e aprender, eu lia manuais, não tinha dinheiro pra fazer IAV, nunca fiz, então eu lia apostilas. Tinham pessoas que me ensinaram algumas coisas, eu pude acompanhar grandes técnicos trabalhando, então você vai absorvendo. Mas foi muito na cabeçada também, de meter a mão e ir pra cima.”

As pessoas notavam o bom trabalho de Adriana e as propostas de trabalho iam aparecendo. Um dia, mixando uma banda na casa de show em que trabalhava, a banda gostou tanto de seu trabalho que passou a chama-la para trabalhar em seus shows. “Eles tinham equipamento próprio, eu ia junto ligava e operava.” Ela enfatiza, “tudo foi aprendizado, todos os processos pelos quais eu passei, todas as bandas. As oportunidades foram aparecendo e eu aproveitava.” Quanto mais ela trabalhava, mais bandas notavam seu trabalho e mais propostas de trabalho ela recebia. Logo, ela começou a viajar com a banda Teatro mágico como técnica de monitor, um divisor de águas em sua carreira. “Era outro esquema, todo mundo de fone, pan pra lá e pra cá, clicks, procedimentos diferentes de trabalho, RF, sistema sem fio; ali eu aprendi muito, eu fiquei três anos lá e quando eu saí muita galera me chamava pra fazer monitor.”

Agora que Adriana é um técnica reconhecida e com muita experiência, conversamos sobre os aspectos técnicos do seu trabalho e as particularidades de trabalhar com som ao vivo no Brasil.

Ao ser perguntada sobre quando começa a adiantar a pré-produção de um show, ela nos contou que “assim que eu recebo o contato, já faço. Tem show que eu recebo um mês antes, tem show grande que a produção técnica do evento já pega os contatos e já começa a pré, tem uns que é três dias antes do show. Eu peço o email, já envio o rider e peço o contrarider, via e-mail ou WhatsApp. Quando não dá pra fazer visita técnica eu peço foto, eu vejo online qual a casa de show. Tudo é formalizado por escrito, tudo que foi acordado, com todo mundo ciente, contratante, diretor técnico, dono da empresa de som ou técnico da casa, envio uma lista com tudo que eu preciso. Depois, se tiver algum problema com algum desses equipamentos, tem que avisar, e se precisar de substituição, tem que avisar com antecedência. E na passagem de som, se algum dos ítens não estiver funcionando perfeitamente, tem que ser resolvido na hora, senão não dá pra fazer o show. Eles sempre dão um jeito, mas tem que ficar em cima, e eu deixo muito claro, eu sou chata. Tem uns caras que dizem ‘ah tá bom, vai tá tudo certo’, e você chega lá e o equipamento é ruim. Então eu digo: se não trocar, não vai ter. Eles dão um jeito e trocam.”

Ao ser perguntada sobre quando começa a adiantar a pré-produção de um show, ela nos contou que “assim que eu recebo o contato, já faço. Tem show que eu recebo um mês antes, tem show grande que a produção técnica do evento já pega os contatos e já começa a pré, tem uns que é três dias antes do show. Eu peço o email, já envio o rider e peço o contrarider, via e-mail ou WhatsApp. Quando não dá pra fazer visita técnica eu peço foto, eu vejo online qual a casa de show. Tudo é formalizado por escrito, tudo que foi acordado, com todo mundo ciente, contratante, diretor técnico, dono da empresa de som ou técnico da casa, envio uma lista com tudo que eu preciso. Depois, se tiver algum problema com algum desses equipamentos, tem que avisar, e se precisar de substituição, tem que avisar com antecedência. E na passagem de som, se algum dos ítens não estiver funcionando perfeitamente, tem que ser resolvido na hora, senão não dá pra fazer o show. Eles sempre dão um jeito, mas tem que ficar em cima, e eu deixo muito claro, eu sou chata. Tem uns caras que dizem ‘ah tá bom, vai tá tudo certo’, e você chega lá e o equipamento é ruim. Então eu digo: se não trocar, não vai ter. Eles dão um jeito e trocam.”

A falta de profissionalismo na pré produção já serve de alerta para Adriana. “Respondem de forma genérica, ‘tem 4 monitores’, mas não dizem qual falante, qual drive, qual tamanho. Aí eu peço foto, porque as vezes só de olhar você já sabe, e já diz se tem que alugar outras caixas, porque essas não vão servir. Se você falar com outro profissional, você envia seu rider, ele manda o contrarider, você negocia o que não te atende e as opções para substituição, e você chega num acordo, só que quando não é um profissional, você não tem como negociar, é difícil, aí eu vou direto no contratante e informo o que está no contrato e o que não está sendo atendido.” Outro problema é quando as pessoas não são nem qualificadas para saber a diferença entre bom e ruim. “Você joga ruído rosa numa caixa e ela não reproduz corretamente, e o técnico diz que tá boa e tá funcionando. Como que um cara que trabalha com som não ouve? Ele não ouve o que tá ruim, ele não ouve nem um humming.”

Em quais consoles Adriana prefere trabalhar? “Eu gosto muito de encontrar mesas boas, gosto muito das mesas Soundcraft linhas Vi, 3000, 2000, gosto muito de Digico SD8 e SD9. Midas e SSL são ótimas mas difíceis de achar.” E o que ela mais costuma encontrar? “Yamaha M7CL e LS9, são equipamentos de muito uso, e se não fazem a manutenção direito, não dá. É o que eu mais pego, mas não entram em nenhum dos meus riders, nem com banda pequena, eu não peço, porque normalmente é o que vai ter. E até atende o input e o output, efeitos, equalizadores gráficos, mas o problema é o mau estado delas.”

Adriana não costuma encontrar equipamentos periféricos além do console, talvez um par de equalizadores gráficos, que muitas vezes não estão funcionando direito, então ela se adaptou a resolver tudo direto no console.

“Eu nem peço, porque pode ter um cabo de insert ruim ou mal colocado, aí o som não chega e você só perde tempo. Melhor ir no console, estou acostumada a trabalhar com qualquer console. O que tiver, você vai e faz. Tenho minhas preferências, mas o que tiver eu faço, não fico dependendo de equipamento. Claro que muda, né, as ferramentas, quanto melhores, mais fácil seu trabalho. Mas eu tô acostumada a torcer M7, LS9 e X32.”

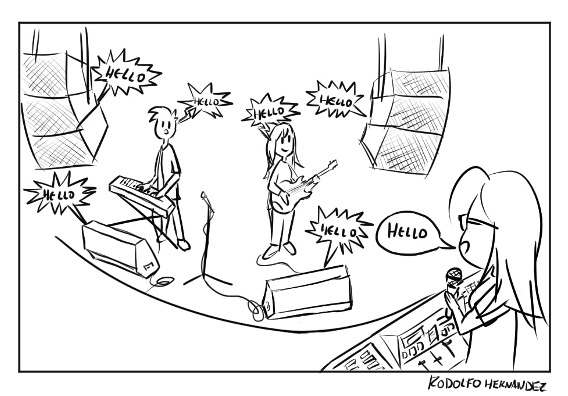

As bandas brasileiras têm uma queixa comum antes de contratar Adriana como técnica de monitor. “O maior problema que as bandas tem é se ouvir. Uma banda que só pode ter um técnico, não vai ter um técnico de monitor, normalmente esse técnico vai fazer o PA. Muitas vezes é um técnico que faz só um show e depois vai embora. Músico que tá acostumado a ter técnico de monitor, se acostuma a se ouvir bem, e no dia que não tem, passa um perrengue.” Por isso, quando Adriana é a única técnica de som na equipe, ela levanta uma mix básica de monitor antes de ir para o PA, porque “enquanto eles não tiverem se ouvindo, eles não vão tocar. Não adianta o PA estar bom se eles estiverem errando, se eles não tiverem se ouvindo. Eu penso assim. Tem gente que não se importa porque foi contratado só pra mixar o PA, mas eu acho que tudo isso agrega no trabalho, se você chega e faz um trabalho mais completo a banda vai te dar muito mais valor e falar ‘a Adriana resolve tudo pra gente, quando for um show maior com cachê melhor a gente aumenta a equipe, mas por enquanto ela é o suficiente’”.

Então as bandas contratam apenas um(a) técnico(a) por causa da verba ou por que acham que não precisa de dois? “Tem bandas em que os músicos estão acostumados a não se ouvir e não tão nem aí. Tem bandas em que eles fazem questão de ter um técnico de monitor, mas a produção não tem verba, prefere chamar algum outro profissional, tipo dançarino ou figurinista, do que priorizar a equipe técnica.” Adriana costuma trabalhar com bandas com uma atitude profissional, e enfatiza que mesmo as bandas pequenas querem cada vez mais ter uma equipe eficiente e buscam contratar no mínimo um técnico de som, um iluminador e um roadie. Quanto maior o show, maior a equipe. Ela faz questão de não ocupar o cargo de roadie, para não tirar o trabalho de outra pessoa e explica para as bandas a importância de ter uma pessoa na equipe dedicada a esse cargo. “No meio do show, se der um imprevisto, quem vai virar as costas pro público pra resolver? O artista não pode resolver isso, tem que ter um roadie pra ir lá resolver o problema no seu instrumento, afinar sua viola no meio do show. Eu tento ao máximo agregar equipe, sempre, eu to acostumada a ter equipe grande porque funciona muito bem e um ajuda o outro, tudo funciona melhor. Eu sempre tento aumentar a equipe e mostrar a importância e a diferença que faz.”

Comparando a realidade brasileira com a americana, Adriana aponta que “aqui você tem que saber fazer tudo: alinhar o sistema, coordenar o RF, mixar PA e monitor, várias coisas. Lá fora é tudo mais setorizado, o que acabando sendo mais organizado. Aqui a gente acaba fazendo tudo porque, se sou só eu e começa a fugir um microfone sem fio, é da parte do som e isso complica o meu trabalho, então eu já garanto o RF. Se for um evento maior, tem que ter uma pessoa pra fazer isso, a casa de show tem que me entregar o equipamento funcionando, mas em shows menores com banda menor que a gente leva nossos próprios microfones e in ears, eu não vou deixar o artista passando sufoco.”

Sobre os problemas técnicos que costuma encontrar, Adriana suspira “a gente passa por muitas coisas”, mas encara essas situações já prevendo como resolver: “se você passa por algo e aprende, você se antecede, previne e toma medidas para evitar que aquilo aconteça, senão você tem que parar o que você está fazendo para resolver um problema. Independente do que seja, você já tenta, os cabos são todos por aqui, já vou fazer o RF, já vou checar tudo, já vou testar antes, logo quando chegar, pra ter tempo, então você vai se antecedendo. Vai dar um monte de imprevisto, cabo que pára e não funciona, canal que entra humming, mas a experiência faz com que você consiga lidar com isso de uma maneira mais rápida. Ok, aconteceu algo, resolve dessa forma; RF tá ruim? Então põe a base no pé da cantora, sabe? Então tem coisas que você já vai tomando medidas mais bruscas para garantir, não dá para perder tempo resolvendo um monte de problema, porque normalmente é só a gente que tá lá pra resolver.”

Falando em prevenir, perguntamos a Adriana o que ela costuma levar para os shows: “Eu levo par de pilha nova sempre, fita, hellerman, toalha, listerine e alcool gel, duas grades de sm58 – se for outro modelo eu limpo, caneta, pen drive. Uma artista reclamou que o microfone tá fedendo? No outro show você já entrega um microfone limpinho. Uma cantora reclamou, eu liguei no dia seguinte pra produção e avisei que tava indo comprar duas bolinhas de microfone e pedi pra ela me depositar. Acabou! Então você tem que achar soluções práticas ao invés de falar que está com problemas. Acho que equipe técnica é isso, achar solução e evitar problema.” No início da ano, Adriana viajou para a Europa com os irmãos, e mesmo sendo uma viagem de férias, ela levou fita. “A gente usou tanto! Colei o tênis do meu irmão que tava abrindo o bico, o livro da minha irmã soltou a capa, passei fita! Meu óculos tinha aberto, prendi com fita. A gente usou tanto, e meus irmãos riram, ‘só você mesmo pra viajar com fita!’. Eu também ando com um multiteste, porque são coisas que podem te salvar. Quanto menos você depender dos outros, menos problema você vai ter.”

Algo que notei ao acompanhar Adriana em montagens e passagens de som, é que ela costuma levantar a cena do zero. “Cada dia é um dia, não é sempre a mesma mesa. Eu tenho muita cena no meu pendrive, mas é difícil usar, já tive que fazer muitas vezes do zero porque a mesa não lia o cartão.” E é claro, cada dia é uma sala e um sistema de PA diferentes. Para verificar a resposta de frequência do sistema, Adriana costuma usar ruído rosa e na sequência tocar suas músicas de referência. “Eu gosto muito de Change The World, do Eric Clapton”, ela também toca versões dub de músicas do The Police para testar os subs. “Costumo usar também Massive Attack, músicas que eu tô acostumada, eu sei o que eu tem um detalhe aqui e ali”. Ela toca Everybody Here Wants you do Jeff Buckley, por causa do reverb longo da caixa, “tem PA que não tem o reverb da caixa, que não tem a resposta dos harmônicos. Tem uns que o stereo está péssimo, tem o stereo de altas, de médias, que estão na mix. Quando chega um backing vocal aberto e não veio, você sabe que aquela região de frequências não está certa.”

Em 10 anos, ela quer continuar fazendo o que está fazendo. Ela gostaria de passar mais tempo no estúdio aprendendo técnicas mais apuradas de captação e mixagem, “mas eu não posso parar de trabalhar para ficar aprendendo no estúdio e ganhando muito pouco. Eu preciso trabalhar. E eu realmente gosto do que eu faço. Tem uns trabalhos que você faz que você se sente parte mesmo. Eu fico feliz quando sei que no dia seguinte tem show do Far From Alaska, ali é a gig do coração! Eu não me vejo fazendo outra coisa. Quando comecei a trabalhar com som, eu nunca mais parei, eu sempre trabalhei muito. E a galera gostava e chamava de novo. Quando você é determinado e se esforça pra fazer o melhor, não importa o que seja, você colhe o que planta.”

Desde que começou sua carreira há 12 anos, Adriana só parou de trabalhar quando estava grávida de sua filha Luka, e mesmo assim trabalhou até os oito meses de gravidez. “Depois que ela nasceu eu fiquei seis meses só em casa com ela, depois eu voltei a trabalhar, por isso eu não tive mais filho, porque eu não posso perder esse timing e financeiramente eu não posso parar de trabalhar. Mas eu gosto muito do que eu faço, e eu gosto de fazer vários trabalhos diferentes ao mesmo tempo, estilos, equipes e produções diferentes, isso tudo é agregador e o aprendizado é maior.”

Desde que começou sua carreira há 12 anos, Adriana só parou de trabalhar quando estava grávida de sua filha Luka, e mesmo assim trabalhou até os oito meses de gravidez. “Depois que ela nasceu eu fiquei seis meses só em casa com ela, depois eu voltei a trabalhar, por isso eu não tive mais filho, porque eu não posso perder esse timing e financeiramente eu não posso parar de trabalhar. Mas eu gosto muito do que eu faço, e eu gosto de fazer vários trabalhos diferentes ao mesmo tempo, estilos, equipes e produções diferentes, isso tudo é agregador e o aprendizado é maior.”

Adriana já foi chamada várias vezes para dar cursos de áudio, mas sua resposta é mais prática e direta: “Vem trabalhar comigo que você pega!”. Uma pessoa inclusive pagou para ter aulas particulares, e ela formulou como repassar todo seu conhecimento da melhor forma possível, mas ao fim ela resumiu “Eu levei muitos anos para aprender tudo isso que eu te ensinei em um mês. Agora, depende de você. Bate em porta de empresa de som, bate em porta de barzinho, casa de show, diz que você está estudando áudio e pede pra acompanhar, se ofereça como assistente. Você quer mesmo? Bate em portas”. Adriana não se sentia a vontade de indica-lo, pois ele não tinha experiência. “Eu aprendi com um técnico que nem sabia para que servia o botão de high pass, ele apertava pra descobrir, mas tudo mais que ele sabia, ele me ensinou. E eu sou muito grata a ele por isso.” Recentemente, Adriana estava mixando PA e no meio do show foi surpreendida pelo técnico que a orientou no início da carreira, ele foi lhe dar um abraço e dizer o quanto estava orgulhoso do seu progresso. “A gente tem que correr atrás. Hoje em dia é fácil, tem muito video, workshop, técnico que vem de fora dar curso, tudo agrega. É importante saber mexer no equipamento, mas o mais importante é saber o que você tem que fazer com esse equipamento. Equipamento é uma ferramenta, como se fosse um computador ou uma máquina de escrever, você pode aprender muito sobre som e audio, e conhecer as ferramentas, mas o mais importante é o ouvido.”

Adriana reforça: se a gente não correr atrás, nada acontece. “Nada caiu no meu colo. As coisas foram acontecendo porque eu ia me mexendo, nunca fiquei parada esperando nada. Graças a Deus todo esse tempo eu não fiquei sem trabalho. Quanto mais você trabalha, mais trabalho aparece. Isto é fato.”

Profile by Gabi Lima, engenheira de audio, produtora, compositora, instrumentista, cantora e comedora de doce.

Profile by Gabi Lima, engenheira de audio, produtora, compositora, instrumentista, cantora e comedora de doce.

Gabi Lima is an audio engineer, producer, songwriter, musician, singer, and candy eater. She is based in São Paulo, Brasil