Mixing: Band Next

In my last blog, I started talking about how you can approach mixing when you’re just getting started. If you haven’t read it, here’s the cliff notes version: vocals are your first priority. Make sure you get the lines out (especially in tech), no matter how many faders you need up at the beginning. Then you can work towards line-by-line mixing from there.

Once you’re comfortable enough with the vocals and can start paying attention to other things, what’s next? If it’s a musical, the answer’s easy: the music.

The band is more self-sufficient than the vocals. They’ll do some dynamics on their own, so they can take care of themselves to a point while you’re settling in with the vocals. For the things they don’t do on their own, you’ll tend to notice and take care of them naturally. If the music is too loud and it’s hard to hear what the actors are saying, you pull it back. If we’re heading into a song, bring them back up to support the singing. All of that is a good start, but at this point, those moves are reactive as you notice something and adjust to compensate. Once you can give more attention to what’s really happening in the music, you can anticipate and be proactive.

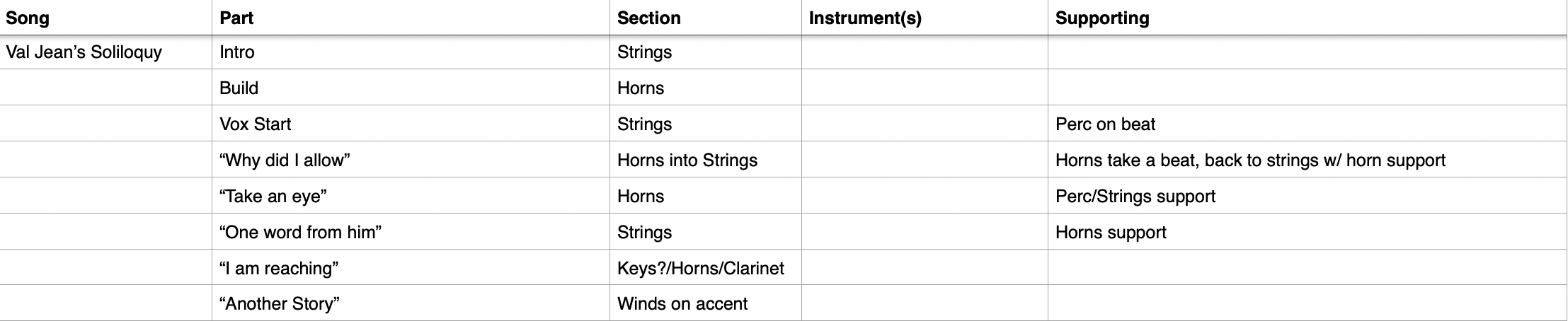

There’s some work you can do even before you get into the theatre. If I’m working on a show that already has a cast album I’ll do what I call a Music Map. I’ll go through each song and write down which section or instrument has the melody or is featured. Even if the recording isn’t the exact version I’m going to do, it gets me in the ballpark. It could be just the sections (brass, strings, percussion, etc), or even a best guess. So what if I mark down that it’s a trumpet that has a solo and it ends up being a French horn? It’s paperwork that’s only for me, so it doesn’t have to be perfect. More than anything it gets me to put a critical ear to the show a few times so I’m more familiar with the music and feel more prepared going into tech.

This was one that I did for Les Mis: it’s a quick jot of “Valjean’s Soliloquy” with the part of the song (usually by the lyric), which section has the focus if I picked out a specific instrument and anything else I noticed like supporting instruments. You can see that it’s a rough sketch, not the end product. There are things like the note of “Keys?” towards the end, which meant I wasn’t sure if it was an acoustic instrument or a keyboard patch. Again, you’ll find out for sure once you get the musicians in the space, but this gives you a reference if you feel like you’re missing something.

Every song has a shape to it. Some get progressively louder, building to a big musical moment at the end, other times it’s a quiet ballad that has some builds but may stay pretty quiet. Others might be a mix or jump from singing into dialogue and back again, going up and down fairly drastically in volume. As the mixer, you help maintain that shape to get the right emotional build. This typically happens in one of two ways: supporting or managing.

When you’re supporting the band your faders move the same way as the dynamics. So you’re riding the fader up with the big crescendo to give the moment a little more punch, or as the music fades you’re bringing it back at the board so they settle where you need it in time to make a pocket for the vocals. This is how you usually treat slow songs (love ballads, dramatic solos) and shows that have a larger, traditional orchestra. Acoustic instruments tend to use more dynamic control, so you’re helping them along.

On the flip side, when you’re managing, that means you’re moving in the opposite direction of what the dynamics are doing. Say there’s a moment where it feels like it should get bigger musically, but logistically what’s happening is only part of the pit was playing at the beginning and when the music feels like it’s going to bump up a notch, the rest of the band comes in. Everything gets louder naturally with the additional musicians, so you don’t need to push to get the dynamic increase you want. You might even have to pull them back to make sure everything doesn’t get too big too early or overpower the singers.

Managing happens more often with electronic instruments, which might not have as much fine control over their dynamics with pedals and presets. In some cases, they don’t have any, like if a keyboard patch is a trigger. That means it doesn’t matter how hard or soft the keyboard player hits the key (velocity), the sound it triggers will always be at the same volume.

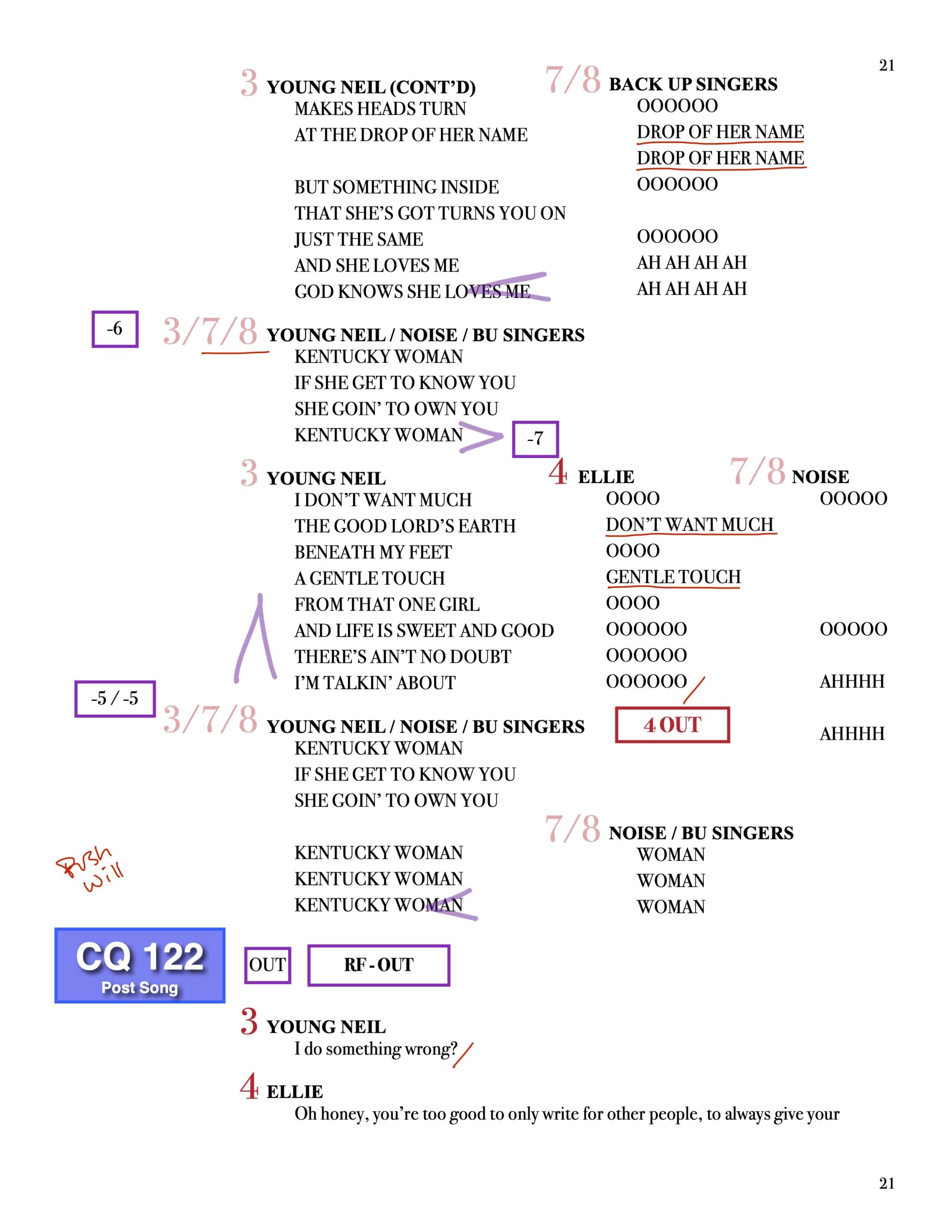

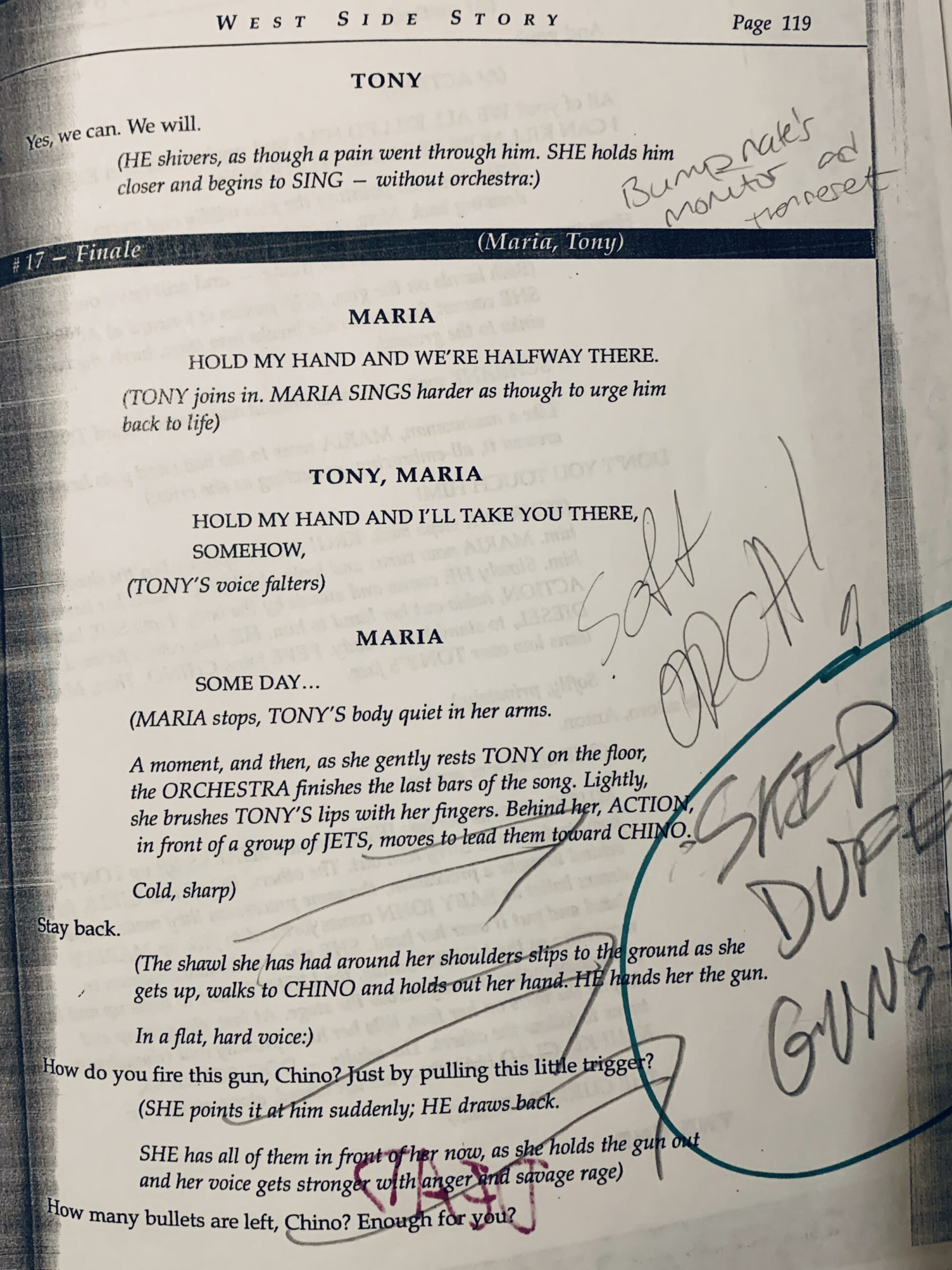

Once you have an idea of the musical shape of the show, start noting band moves in your script. These will become a part of your choreography. I’ll use numbers if I know where the band faders usually end up, or markings like crescendo, decrescendo, or circles for quick bumps if the moves are more general.

Along with overall dynamic moments, you’ll also begin to pick out individual solos or features where you may have to give additional support or managing, just on a smaller scale. For example, if a flute and a trumpet each have a moment in a song, they’ll likely have to be treated differently. The flute is naturally quieter, so you’ll likely have to push their mic to get them out over the mix. However, the trumpet may not need any help (or you might have to pull it back) depending on the player’s lung capacity and sense of subtlety.

Try to remember that no rule is absolute. Although trumpet players are very good at being loud, that doesn’t mean you’ll always pull them back. In Mean Girls, there were a couple of moments where the trumpet had a James Bond-style riff and I’d have to push it quite a bit to get them out over the rest of the band. So treat each moment as its own entity. In sound it’s easy to get caught in traps of comfort and appearance: an eq doesn’t look quite right, and you never usually have to push the drums, so why would you need to now? Try to listen first and make adjustments accordingly. Does the eq sound right? Can you not hear cymbals in this section? When in doubt, ask for a second opinion. Sometimes you just need a set of fresh ears when you’ve been listening to the same show for weeks or months.

Once you learn where the band moves are, you can focus on the details. Different songs will want different approaches: sweeping orchestras lend themselves to fluid, continuous movements while quick, pop songs tend to have quicker bumps or more dramatic pulls.

Here’s a video of “Why God Why?” from Miss Saigon. It’s mostly one person singing, so the attention is on the band’s moves. My main focus is to make sure the vocals (faders 1-8) are always supported—not overpowered—by the orchestra (11 and 12), but I can still fill in the music around the lyrics so the overall level stays consistent. There are pushes with the orchestra in the emotional builds which are followed by quick pulls to get the band back and make a pocket for the vocals again. Around the 3:35 mark, there’s a pull where I tuck fader 11 back a little bit more than the rest of the band to compensate for a louder key patch: an example of the managing I talked about before in action. Overall, the song starts out quiet and has slow builds, each getting a bit bigger than the one before. There’s a quick pullback when we go into the faster section, the emotional build with Chris and the Vietnamese, and then the big finish at the end with a bump.

Music is an essential part of a musical, but it can do so much to enhance the story on an emotional level. As a mixer, you get the chance to put an extra flourish on some of those moments to drive them home. One of my previous blogs covered some of those times in-depth and how good it feels when everything comes together. Because the next level of working with the band is learning to adjust it live to the actors so you get that emotional impact. When they’re able to go for it, you have more leeway to make the moments bigger, or if they’re under the weather or having an off day, you adapt and pull the music back so they still land in the right place relatively. Like in “Why God,” you can literally hear Chris’s frustration building as the orchestra gets bigger, but how big the orchestra can get depends on how big Chris is going to go.

It’s these details with the music that make a lot of shows more fun to mix. There’s a feeling you get when you hit a bump at just the right moment and just the right level that keeps you coming back to see if you can do it again and again. I’ve been incredibly lucky that I’ve worked with some people who are both amazing musicians and lovely humans, and you always want to let that talent shine. I can’t count the number of times one of them has come up to me, so excited because a friend came to see the show and told them they sounded good. If they know that you’re taking care of them, you build trust, which ultimately leads to a better show for everyone. So take the time and make the effort to learn the music. Some people will actually notice and appreciate it, others will just know that the show hit a little deeper this time. Either way, it can make a world of difference.