Fielding Feedback

Sound is a department that a lot of people don’t understand, but everyone has an opinion about it. Learning how to navigate notes, complaints, and feedback (the people kind, not the speaker kind!) is a skill that’s imperative for your sanity in this career. So how do you deal with them?

Let’s start with the creative team. Obviously, whatever notes or feedback you get from your design team you should take and implement. It’s their job to fine tune the mix and tech is an excellent time to pick their brain so you can learn why they’ve made certain decisions, and then you yourself can make more informed choices when they’re no longer in the room.

Getting notes isn’t a bad thing. Sometimes it feels like it’s an inherently negative experience because people are telling you all the things you did wrong during the show, but it’s better if you can frame it as improving so you can level up your skills or your show.

Unfortunately, that’s not to say you won’t run in to people who are insensitive or even deliberately harsh when giving notes. I had an A1 who would give me notes one day then, on another day, give me additional feedback that seemed to contradict what he had said before. Another time, when I was learning the mix, the notes I got from the A1 was that “it was bad” and I “needed to do better.” Which felt like it was intended to knock me down a peg and make me feel insecure.

If notes don’t make sense, ask them to clarify. If what they’re saying feels cruel, that’s harder to unpack. In my example, I wish I’d had the wherewithal to ask my A1 to be more specific so I had actionable items to work on instead of a sense of general, unhelpful disapproval. Sometimes it’s simple as starting a conversation about how their tone is coming across, but that’s not always the case. If you don’t think you can have a productive dialogue with the person noting you, but do feel comfortable talking to someone else on the team, go to them and ask for advice.

If you’re an A1 noting your A2, it’s good to remember that in many cases, mixing is not necessarily something they consider their primary job. Some career A2s enjoy mixing, but others do it because it’s an expectation of the job and still get nervous at the console.

The most important thing is to be specific with your notes. Don’t just say it was bad, talk about what happened and the best way to fix it. (Again, harsh language like that is asking for confidence issues and potentially creating bad blood in your department.)

Acknowledge mistakes, but don’t harp on them if the mixer already knows. Missed pick ups are a fairly obvious thing, so I usually say something like “you missed that line, but you already know that.” That way they know I was paying attention, but we’re not spending extra time when the solution is to not miss it in the future.

If there are repeat problems, ask for feedback. What seems to be tripping them up? Helping someone’s mix improve is a two-way street.

All that being said, if you think your creatives can be harsh critics, I’d like to introduce you to your audience.

There’s a Cracked article by Jason Pargin that I love. I’ve had it saved as my browser homepage for probably the last five or so years (probably more). The premise of the article is a “New Year New Me” feel, but with a side of smack-you-upside-the-head realism. It asks what you can DO. Not if you’re a nice person or have a lack of faults, but what skills do you have?

It’s well worth the read.

It makes a point that when you make something, people will feel the need to comment on, criticize, and critique it. When you put something creative into the world you are inviting that world to tell you how you’ve done it wrong. Cue the audience. Those who’ve never attempted to do it (and have no idea what goes into it) are sure they could do it better and all those Karens will happily tell you that your work is simply not up to snuff. After more than a decade at the console, I’ve met plenty of them.

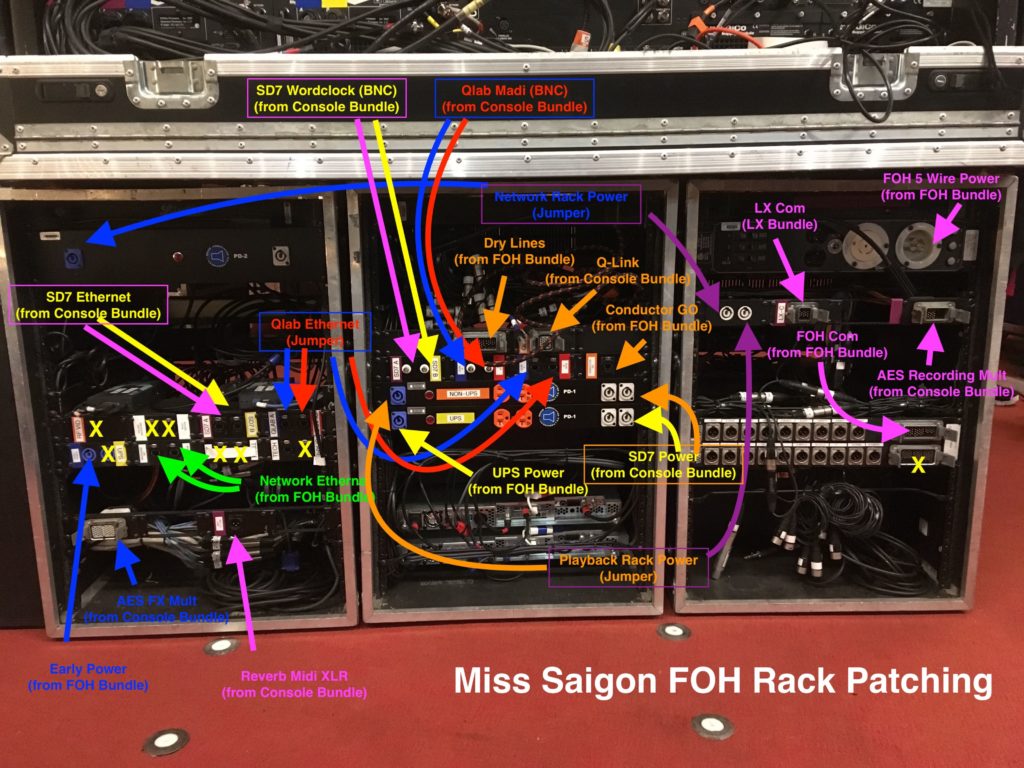

When I was on Saigon, I had one man stand by FOH and tell me that the show sounded bad and just kept repeating that until I had exhausted my usual polite responses, hit the end of my patience, and finally told him he was being rude. To which he responded “I’m not rude, I’m telling you it’s bad” and huffed off.

In another venue we had a 45 minutes show hold for automation which resulted in four pages of audience complaints which ranged from “I can’t believe they still had intermission after we already had to wait for 45 minutes” to “we held for so long and the sound wasn’t fixed when they restarted.”

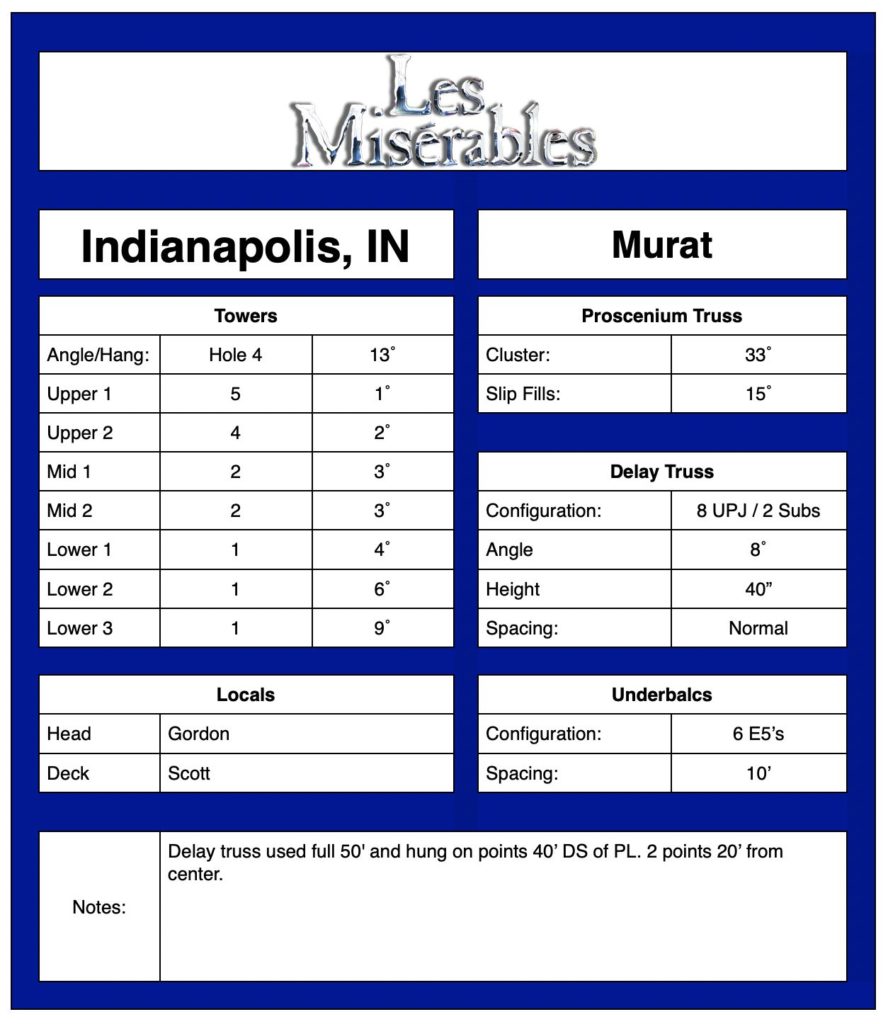

On Les Mis, I had someone tell me that he’s seen the show 25 times and he knew how it was supposed to sound.

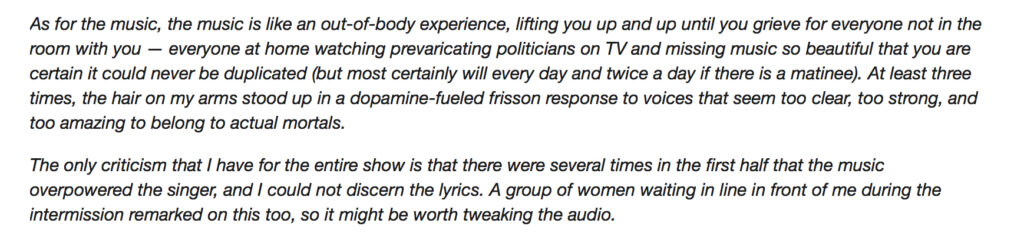

I’ve forgotten the venue but there was an online review that I kept a screenshot of because I couldn’t help but laugh at the perfect example of what we struggle with every day:

Credit is usually given to the actors. Criticism is usually given to the crew. The sounds they heard that were indeed too clear and strong to come from a mere mortal since it was in reality coming from a sound system that created both the “out of body experience” and the times they had trouble with the lyrics.

Pro Tip: don’t go fishing for reviews. People like to criticize and complain much more than they like to compliment (again, reference the Cracked article’s point).

In one theatre I was warned by the house head that the venue gave out free drink tickets to mollify people who complained, so shows always got a lot of complaints because patrons knew they’d get the tickets.

On Outsiders I had a man come up to tell me that the show sounded atrocious.

We’d also had a couple complaints over a few shows that the speaker in front of them (a side fill) wasn’t working. I double checked and it was, but they were reacting to the fact that it was delayed in such a way that you placed the sound as coming from the stage instead of sourcing to that particular speaker.

Sometimes you’ll have a person come up and complain and someone else right behind them will overhear and tell you they could hear everything perfectly fine.

Some are trying to be helpful and alert you of a potential problem. Some want to talk to your manager. Some just want to be right. Others might have hearing issues that they don’t even know about. I’ve worked in theatres with seating capacities from 1,000 to 4,000 and it’s nearly impossible to make every single one of those people happy.

Most of the time, dealing with complaints in the moment is fairly easy. I’ll usually ask them where they’re sitting and tell them that we’ll look into the problem.

The belligerent ones and the Karens are the outliers. If anyone won’t take a simple answer, send them to House Management and say those employees can better deal with their feedback.

My general rule for complaints is:

One person puts me on alert: there might be something wrong, but it’s doesn’t require immediate action.

Two complaints will put me on guard: I might need to do something, so let’s make some cursory looks at potential reasons for a problem.

Three or more means that something likely is wrong and I need to actively look into making a change.

The logistics of dealing with complaints is usually simple, the bigger issue is that it’s very easy for them to get under your skin. Now that someone has told you something’s wrong, you start to second guess what you’re doing and how it sounds.

Unfortunately, there’s no easy way to develop a thick skin so you can mix through negative feedback, but it’s almost an essential for mixers.

When in doubt, circle back to your team. If you’re in the same city as your designer, ask them to come back and note (or if they’ve already gotten feedback from other people who’ve been by to note the show). If you’re on tour, ask someone who’s been out to listen recently (PSM, resident director, conductor) if things still sound consistent, or ask if they can come out to listen at some point. Get out in the house yourself while the A2 is mixing (if there’s time in the backstage track). You can learn a lot about how everything comes together when you’re able to get out from FOH and walk around the balconies and the sides and hear how the mix translates to the other areas of the theatre.

At the end of the day, you were hired because they trusted you to do your job. Notes are meant to help you do the best job you can, and audience members will keep you humble. Treat everyone with respect (unless they fail to respect you in turn), and keep trying to learn.