Old Script, New Tricks

Sound people have a lot of opinions so there are always things we can debate. One of the bigger ones concerns scripts. Do you always have one in front of you or should you memorize the show? Is a digital or paper script better? Everything has its pros and cons, even down to what’s the most efficient way to turn pages.

For several years, early in my career, I worked with a designer who preferred that his mixers be off-book as quickly as possible, so I developed the habit of memorizing the show and getting rid of the script. Now I find something satisfying about walking up to a console that is clear of all clutter: no script tray, no extra lights, no knick-knacks, just you and the board.

There are sometimes you have to use a script. For shorter shows (a couple months or less) or readings and workshops (typically a couple days at most), there simply isn’t enough time to confidently be off-book. With any new show things can (and will) change daily and it’s always better to have a script in front of you to document and stay on top of everything.

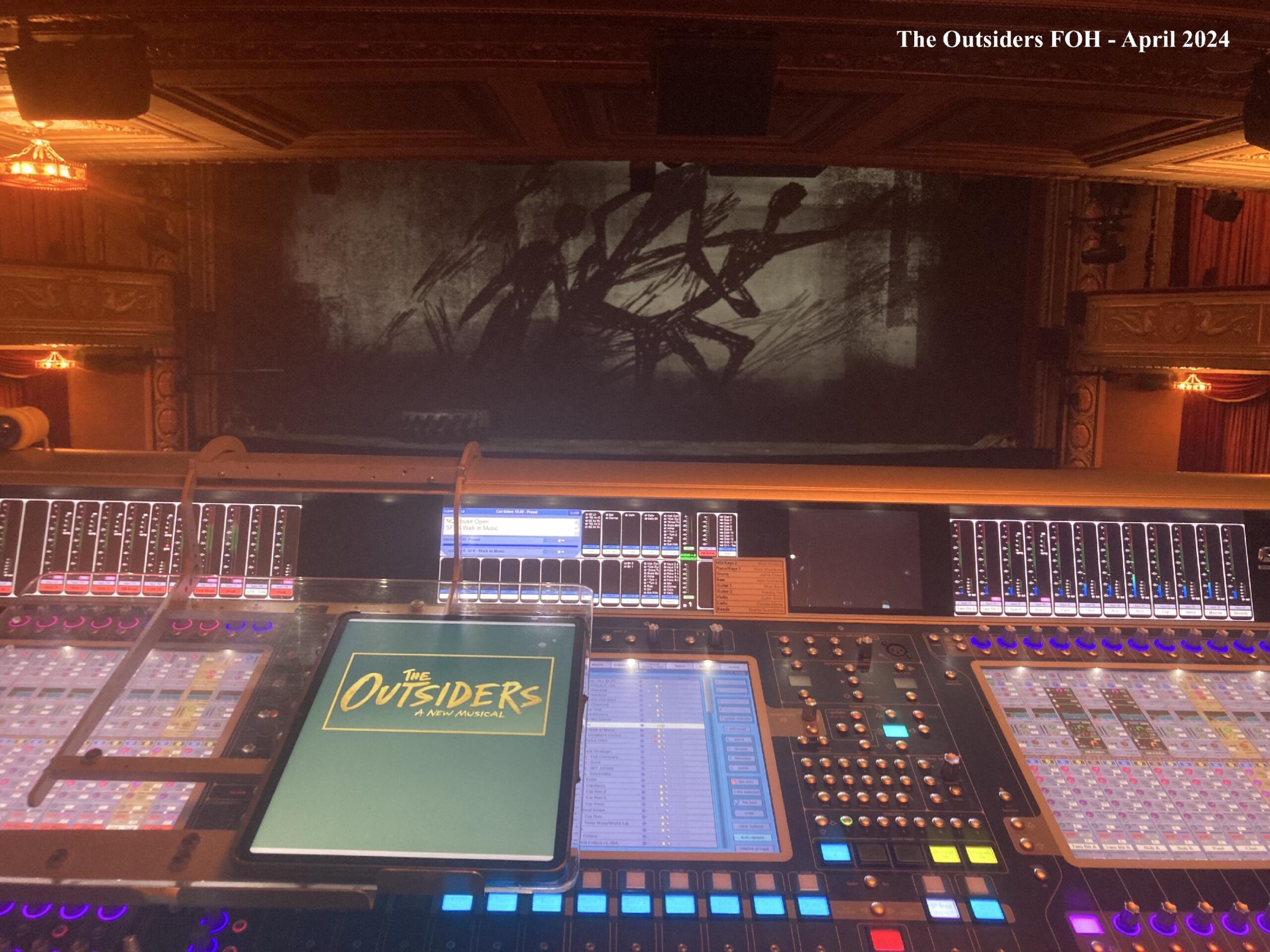

On Outsiders I ran into a new situation. I was on a show that would hopefully run for a while, so the goal, as usual, was to get off-book. However it was a new show, so from December when I saw a reading of the show until we opened five months later in April, I needed a script to keep track of all the changes.

I found prepping a new show was a completely different process from an established one. On tour, you can memorize months ahead of time, knowing things may change, but they’ll likely be minor at best. On a new show everything is in flux: pieces of songs were added or rearranged, lines got reassigned, and whole sections got cut, added, or moved on a daily basis. There were things we were running for the first or second time during a preview performance, so trying to memorize ahead of time would have been a pipe dream at best.

On my previous shows, I was completely off-book within a month or two of opening. With an April opening for Outsiders, operating under a similar timeline put the show in the middle of having Tony voters in the audience, a time where making any mistakes would be frowned upon, let alone missing something because I chose not to have my script in front of me.

With that in mind I knew that I’d be on-book until at least mid-June, after the Tonys, what I didn’t expect was how hard it would be to get off-book once I was so used to having it in front of me. I’d learned to rely on it instead of having the show memorized and it was a comfortable safety blanket. Logically, there’s no reason besides personal preference to not have my script in front of me so it was another two months before I felt completely comfortable putting it away. And I only pushed to do that because I was training a sub on the mix and I’ve always found it easier when you don’t have to share the script dolly or swap back and forth between books.

After seeing both sides of things, what’s my recommendation?

Whatever works best for you, maybe with some weight given to the specific preference of the designer.

Having a script means you don’t have to rely on your memory and the show typically drifts less because everything is right in front of you. However, there is more of a tendency to look only at the script and pay less attention to what’s going on onstage.

This is especially true for newer mixers who have to look down at their hands to make sure they’re hitting the correct levels for pick ups and read the script for the next thing. That’s a lot to do on it’s own without adding in looking up at the stage.

More experienced mixers tend to have a muscle memory for fader throws so they don’t have to look at their hands as much to know they’re hitting close to -5dB or -10 or whatever they need. For them it’s easier to divide their attention between two places (script and stage) instead of three. Which was true for me. So even though I was still on-book for Outsiders, I already had the habit of getting my head up and paying more attention to the stage and was able to find a happy medium.

The benefit of being memorized is that you don’t have anything in front of you besides the show. When you’re looking at the stage you automatically start to connect what you’re hearing to match the visual onstage.

Physically you don’t have as many things covering the console when you need to make adjustments (the script dolly for the SD7 blocks a lot of real estate). But, you’re relying solely on memory which can be faulty: it’s easier to forget things and miss pick ups or drift as you think you remember the levels you usually hit, but it starts changing slowly over time.

Again, do whatever makes you the most comfortable.

Now I know that I like the comfort of having a script just as much as I like the look of an uncluttered console. On the flip side, I also realized that I pay better attention when I don’t have the script in front of me.

I went through a few waves as the show progressed. At the beginning I was focused while I was still learning the show. Once I got comfortable my mind started drifting. That was when I started trying to get off-book, and that challenge pulled my focus back in again. Honestly, I think I’ll stay off-book for the majority of the time, but still pull my script out every once in a while to make sure I haven’t drifted or if I gone for a week or two on vacation.

The biggest improvement is that I wouldn’t beat myself up for having (or choosing) to pull out the script. Before it would have been a failing that I’d “lost my touch” or didn’t know the show anymore, but now it’s getting to revisit an old, helpful friend.

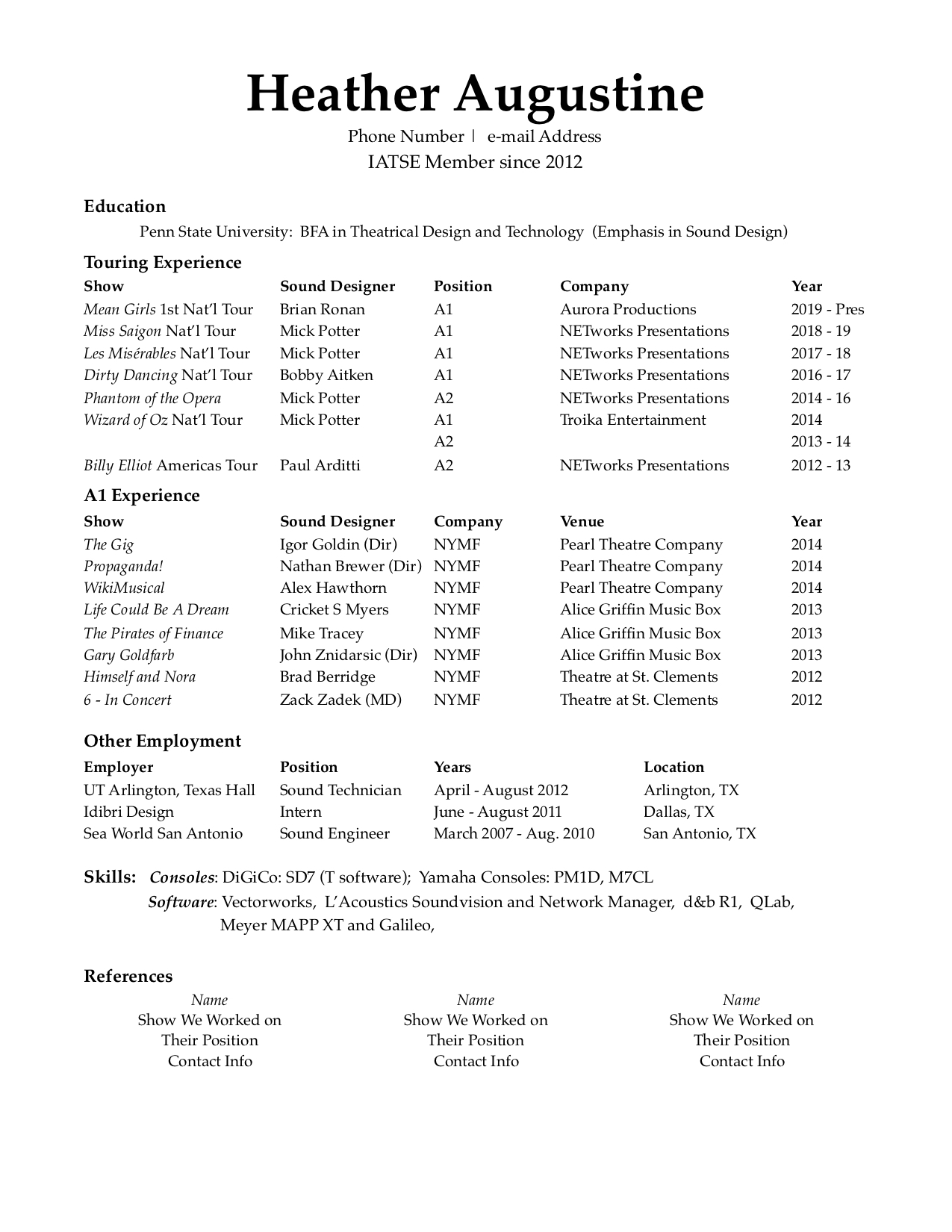

I had a taste of that when I hopped back to the Les Mis tour last year to cover the A2’s vacation. I had a couple shows out front to refresh on the mix and, even though I’d been off-book when I was on the tour before, it would have been egotistical to a fault to think that I still remembered everything six year and four shows later, so the script came back out.

Past the opinions of on- or off-book, there’s also a debate on using a digital script (iPad, Surface, etc) or sticking to a physical hard copy. I prefer a digital script: I find it easier to make clean changes, and it was very useful when I was subbing on multiple shows because all my scripts were in my iPad instead of carting around multiple binders. On the flip side, paper never runs the risk of running out of battery, and if you need to change a page you just pull it out and put the new one in instead of dealing with transferring files. I never ended up needing them, but I still had a paper copy of my script at each show, just in case.

So, I guess I do a hybrid approach. I use my digital script (with a charger set up at the console) but I also have that hard copy. Which would also come in handy if I got hit by a bus: there’s always a copy of the script at FOH for someone to grab.

Again, it’s all about your own comfort level.

If you like the convenience of having everything self contained and don’t want to deal with an extra light at the console, digital is the way to go, just make sure you keep an eye on battery level and have a charged pen to go with it.

If the possibility of your script dying at a random point in the show gives you anxiety, stick with the tried and true hard copy.

There are endless other debates: do you use the version that the SM gives you or make your own? If you have a digital script do you want to minimize how many times your hands move off the faders and add in a foot pedal to turn pages for you or do you bite the bullet and doing it manually?

For me, I make my own script and put page turns in the most convenient spots which makes adding in a foot pedal feel too complicated for a minimal benefit. If I want to turn pages less I just get off-book and call it good.

Does any of this mean that’s how you have to do it? Absolutely not.

I try to give you multiple opinions of whatever I’m talking about because nothing in this industry is one-size-fits-all. Listen to people and their opinions. Use what makes sense to you, but maybe try something new to see if it might work better for you. Before I did Outsiders I never would have thought that I’d actually like having a script in front of me, but I got to try something new and it worked. Doesn’t matter how old the (road) dogs are, we can still learn new tricks.