My Take on Line-By-Line Mixing for Theatre

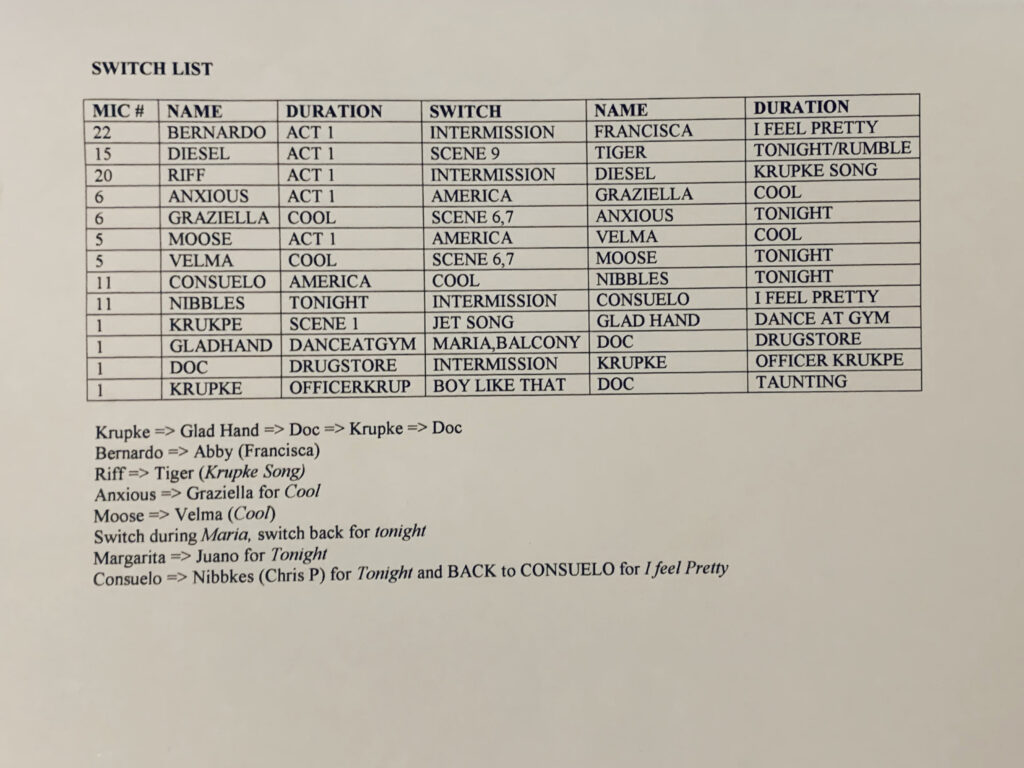

Theatre sound

Since I had started as a live sound engineer for theatre, I didn’t really pay attention to other mixing styles. Line-by-line mixing made sense to me and was my natural technique. It wasn’t until I started working with musical artists and bands that I realized I needed to change my approach. I was not a live sound music mixer, I am a theatrical mixer, and there was a learning curve for me. Line-by-line at the most minimal means you are opening/closing mics for each person coming on and going offstage. Mute groups, DCA/VCA, and automated scenes REALLY help when you have a ton of radio mics. Mixing for an orchestra plus 15-25+ wireless mics were the norm for me while in college (& working professionally later).

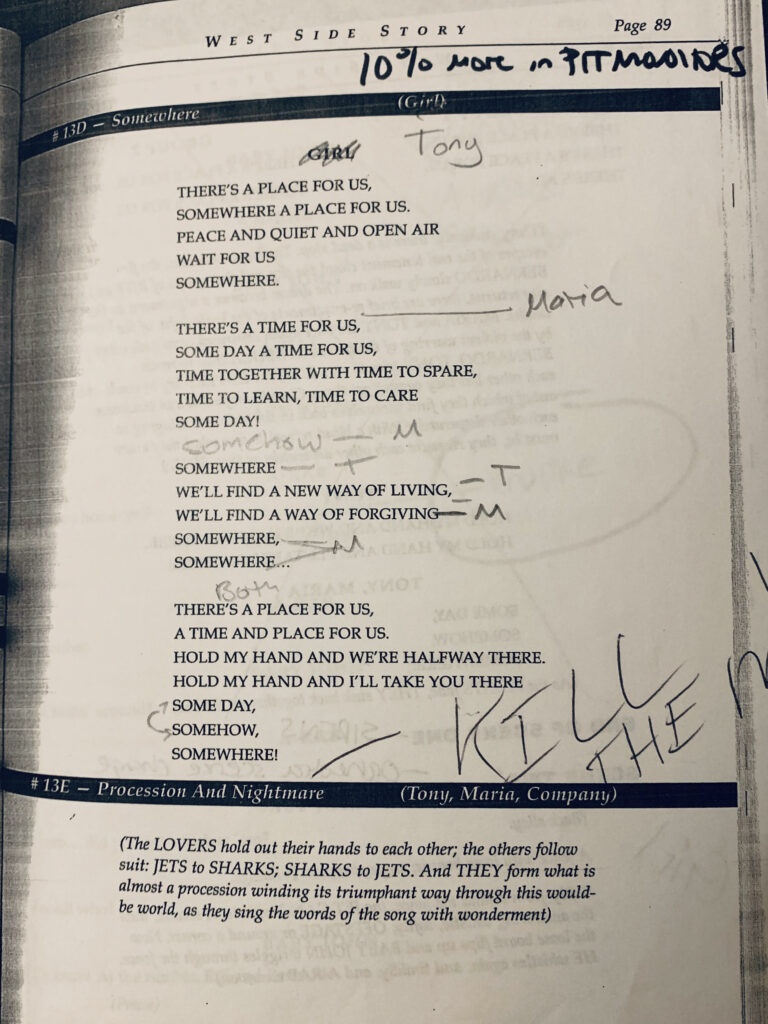

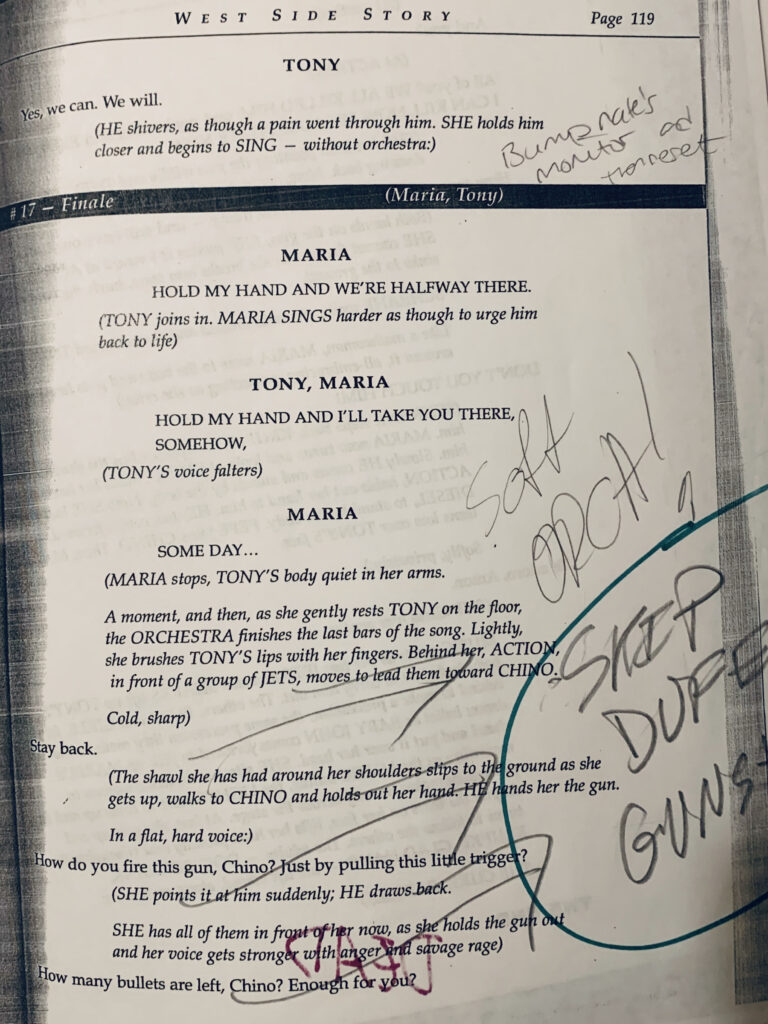

We were taught to read a script a minimum of three times. Script analysis was integral for sound design, as it forces academic research. The first time you read a script is the most important as you are forming first impressions and understanding of the story. The second read-through was sometimes done with other designers, actors, director, etc. but I felt they often left out the tech crew. The second was to solidify the understanding of the themes, subjects, and tonality. The third and subsequent read-throughs of the script are for writing SFX cues, entrances, and exits (if not in the script OR noting they will go off and immediately return), orchestral solos, and grouping of singers.

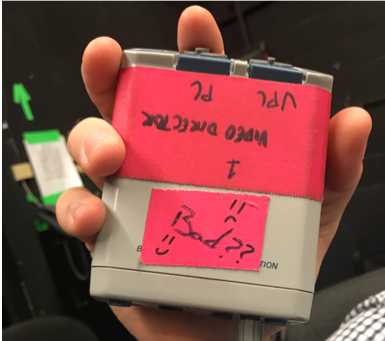

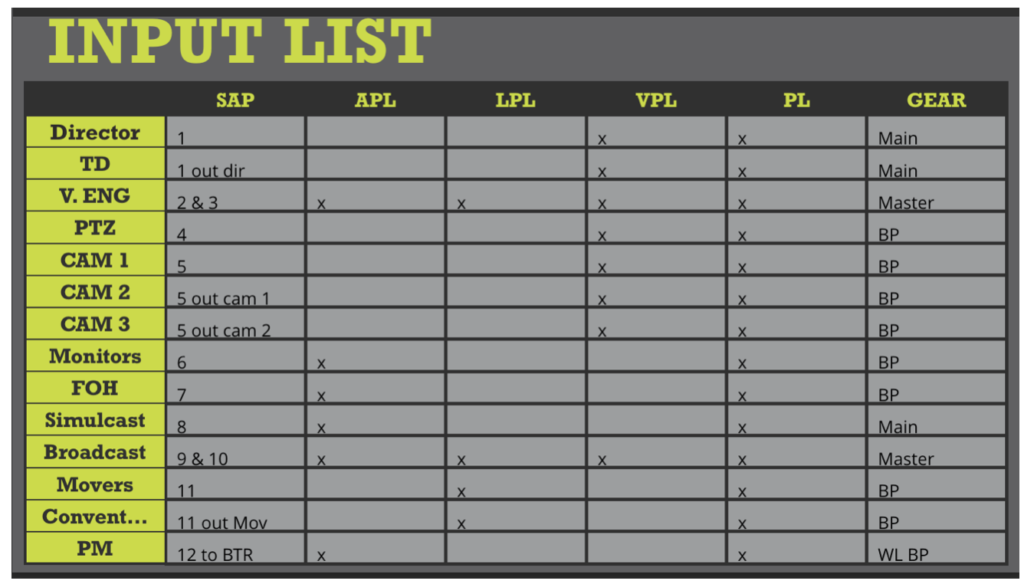

In rehearsals and the tech week process, there was always a lot of “hurry up and wait” while we all made adjustments. This was a valuable time for note-taking; if my script was thorough and accurate, I would be able to focus more on the mix rather than who the hell is onstage right now. An Audio Engineer for the theatre is a lot of things: FOH, foldback, A2, RF Tech, systems engineer, sound effects operator, comms, and so many other little things. Keeping organized was the most important because we have a lot of shit to handle.

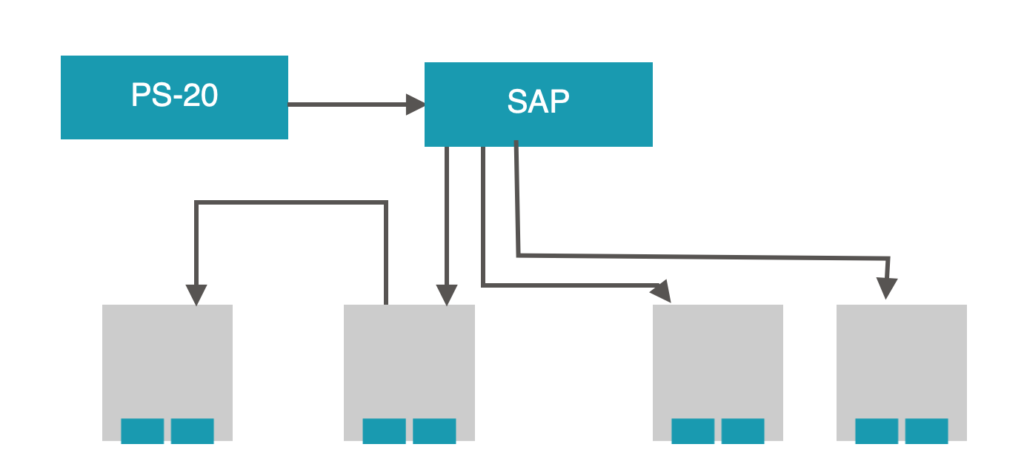

Once you know who is doing what on stage, which solos or special parts the orchestra has (which is why attending the sitzprobe is integral for success, ( In opera and musical theatre, a sitzprobe (from the German for seated rehearsal) is a rehearsal where the singers sing with the orchestra, focusing attention on integrating the two groups, it is often the first rehearsal where the orchestra and singers rehearse together.) You can build your show file and program the console. The Stage Manager will be able to call your SFX cues (and sometimes even run them) so I make notes and place trust in my SM. I learned how to mix on an Allen & Heath ML4000 (?? TBH it was over 13 years ago), so my brain is focused on having as much as possible in front of me. Layers are where I hide things that don’t need to be actively mixed, as I do not like switching between layers quickly.

My Console Setup

Once everything is labeled and organized, I start with assigning VCAs/DCAs (Showing my experience/age). Wind, strings, rhythm, etc. will each get a DCA if it’s a larger orchestra. Orchestra overall gets a DCA. Ensemble (separated men/women), and quartet/trios should also get their own DCA. Some of these may be assigned to a group instead of processing, which will depend on the situation. Mute groups are your best friend, it takes some time to program them on older consoles, but it is worth the effort. Depending on your digital console, recording scenes or screenshots while in rehearsals would be the best option. You can always make small edits later if your timing isn’t quite perfect. From there, it’s all about the notes from rehearsal. Line-by-line was the most logical method for theatre & I still think this way during productions.