Asle Karstad – Mic Tips for Acoustic Instruments

On the last day in February, Soundgirls.org – in cooperation with KRETS (Norway) – arranged a day with Asle Karstad, who gave a lecture on the reinforcement of acoustic instruments.

On the last day in February, Soundgirls.org – in cooperation with KRETS (Norway) – arranged a day with Asle Karstad, who gave a lecture on the reinforcement of acoustic instruments.

Asle Karstad has worked for over 35 years in sound, and and refers to himself as a ‘sound producer’ – the person who guides the sound so the listener will get the most optimal experience. He has spent most of his time working with the Oslo Symphonic Orchestra, but is also very well known by Norwegian Jazz and folk musicians.

On this particular day Asle had been kind enough to invite some friends to join him – an acoustic guitar player, a quartet from Norwegian Radio Orchestra and a well known contrabass player by the name Ellen Andrea Wang.

We were very excited to meet Asle in this relatively new venue in Oslo.

Sentralen is only a year old and contains five separate and diverse concert rooms. (If you happen to visit Oslo, don’t miss out on visiting this very special venue.)

Asle’s first mission was to show us how you find the resonant frequency of an acoustic string instrument – or the ‘Crazy Note’ as he refers to it. (The resonant frequency is the natural ‘note’ that the instrument will create on it’s own as soon as you ‘put’ some energy into it, for example by tapping on it.) The reason Asle places importance on finding the ‘Crazy Note’ – is because he discovered that when six violin players put down their instrument at the same time, the little bump on the floor creates the resonant frequency, which could lead to feedback from the six violins in close proximity with each other. The resonant frequency of a violin will be around 275 Hz – 280 Hz. Their fundamental note is 94 Hz.

Asle’s first mission was to show us how you find the resonant frequency of an acoustic string instrument – or the ‘Crazy Note’ as he refers to it. (The resonant frequency is the natural ‘note’ that the instrument will create on it’s own as soon as you ‘put’ some energy into it, for example by tapping on it.) The reason Asle places importance on finding the ‘Crazy Note’ – is because he discovered that when six violin players put down their instrument at the same time, the little bump on the floor creates the resonant frequency, which could lead to feedback from the six violins in close proximity with each other. The resonant frequency of a violin will be around 275 Hz – 280 Hz. Their fundamental note is 94 Hz.

The method he used to find the ‘Crazy Note’ was to place the instrument on a table and close mic it where the resonant frequency was assumed to be found (Asle was using a DPA 4011 as microphone). He would then tap around the body of the instrument, and take a ‘snapshot’ of the frequency response.

The method he used to find the ‘Crazy Note’ was to place the instrument on a table and close mic it where the resonant frequency was assumed to be found (Asle was using a DPA 4011 as microphone). He would then tap around the body of the instrument, and take a ‘snapshot’ of the frequency response.

By using this method we discovered that the instrument has one spectacular note in the lower range that stands out- the crazy note! (If you try this yourself, remember to dampen the strings so they don’t resonate – a towel works well)

It’s important to find this frequency because you may have to deal with other issues in the low end, like for example the low hum that likes to ‘sneak’ around your PA and end up in your mic’s on stage. If that ‘hum’ happens to be the same frequency as the ‘Crazy Note’ on one or more of the acoustic instruments in the orchestra, you could quite quickly end up with a problem.

Asle reminded us that it is always good to consider that the low end has a tendency to travel around the speakers and up on the stage, higher frequencies, as we know are more directional and therefore don’t have the same problem. This is also why we like to close mic, to eliminate ‘sneaky’ low end frequencies from PA and the room itself.

Asle reminded us that it is always good to consider that the low end has a tendency to travel around the speakers and up on the stage, higher frequencies, as we know are more directional and therefore don’t have the same problem. This is also why we like to close mic, to eliminate ‘sneaky’ low end frequencies from PA and the room itself.

Whilst we are thinking about resonance – we also have to remember that any kind of resonant shell acts like an amplifier. You will do yourself a favor knowing the resonant frequencies of your acoustic instruments in advance to deal with any issues. For example the resonant frequency or ‘crazy note’ of an acoustic guitar will most likely be around 200 Hz. Asle suggested, when you pull that frequency out of your acoustic guitar that you add a little decay to it around 1,85 – 3,25 seconds to keep the natural sound to it.

Here are some other resonant notes to remember: Cello 80 – 90 Hz, Contra Bass 105 Hz (105 Hz goes for electric bass too). Asle suggest to ‘work’ a little around 65 – 105 Hz, since you will have the low end energy from the PA in this area as well.

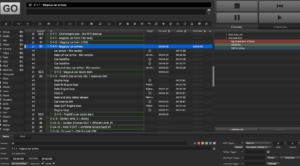

Some other interesting tips from Asle are to put a compressor on the reverb send for your acoustic strings. And if you do not want ‘things right up in your face’ as he puts it, delay the whole mix 6 – 9 ms. We tried this and it made a huge difference, it somehow also made the mix sounds bigger and brighter.

Some other interesting tips from Asle are to put a compressor on the reverb send for your acoustic strings. And if you do not want ‘things right up in your face’ as he puts it, delay the whole mix 6 – 9 ms. We tried this and it made a huge difference, it somehow also made the mix sounds bigger and brighter.

Also to make your mix sound more natural you might want to put a high shelf cut on your strings from 1500 Hz and up – it sounds crazy, but if you think about it, higher frequencies die quickly over a distance. We felt this method worked.

Regarding string instruments – aim the capsule at the wood when you mic up – not for the strings!

KRETS is a part of the Norwegian music organization that was founded in 2013, as a tribute to the 100 year anniversary for the Women’s Right to Vote in Norway. The group is trying to connect female technicians across Norway by supporting events like this one with Asle Karstad. Soundgirls.org would like to thank KRETS for their co-operation and support.