Being Bilingual Does Not Always Work

By Andrea Arenas / Collaborated by Vanessa Montilla

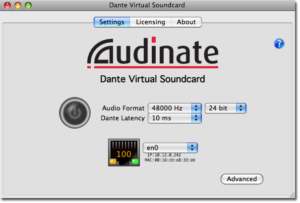

It is possible that you have done several language courses. However, nothing prepares you to work day-to-day as a sound engineer, if you are on tour in a country where a language other than your native language is spoken. It is likely that no matter how many courses you do, you have not been taught how to “comb the wires” (slang for ¨Untangle the wires¨ in Spanish), and many words of technical, and even everyday jargon.

That is why I have decided to make a small glossary of objects commonly used in audio but that you may not find in any book of system design or recording techniques, and that therefore you are not accustomed to using in a language other than of yours. I hope it is useful for you and that we can also complete it in different languages.

Cables

-

Español: XLR / Cannon

English: XLR English

-

Españo: Pasacables

English: Yellow Jackets

-

Español: Cable de puente o extensión

English: PowerCon Jumper

-

Español: Plug balanceado, Jack

English: TRS, Balanced 1/4 inch

-

Español: Plug desbalanceado, Jack

English: TS, Unbalanced 1/4 inch

-

Español: Cable blindado o apantallado

English: Shielded Cable

Conectores/Connectors

-

Español: Multipin de 12

English: W1 (12)

-

Español: Multipin de 16

English: W2 (16-20)

-

Español: Multipin de 56

English: W4 (56)

-

Español: Socapex

English: Socapex/ Soco

-

Español: Speakon

English: NL4

-

Español: Speakon

English: NL8

Audio

-

Español: Consola / Mesa

English: Mixer/Board

-

Español: Audifonos/Cascos

English: Headphones

-

Español: Audiofonos

English: In-Ears

-

Español: Belt-Pack

English: Belt-Pack

-

Español: Parlante / Monitor / Corneta

English: Speaker/Monitor

-

Español: Monitor de piso

English: Wedge/Monitor

-

Español: Micrófono Inalámbrico

English: Hand-held Mic

-

Español: Caja directa

English: DI Box

-

Español: Paral / Atril

English: Mic Stand

-

Español: Brazo

English: Boom

-

Español: Caña

English: Boom

-

Español: Cuello de ganzo

English: Gooseneck

-

Español: Balita

English: Lavalier

-

Español: Intercom

English: Com

-

Español: Auricular / Inalámbrico

English: Headset

-

Español: Pinza

English: Mic Clip

-

Español: Cartuchera / Estuche

English: Pouch/Bag

-

Español: Adaptador de paral

English: Quick Release

Electricidad / Electrics

-

Español: Cable de corriente/ Cable de alimentación

English: Power Cord (90 IEC)

-

Español: Regleta / Multicontacto

English: Power Strip

-

Español: Enchufe / Toma corriente

English: Outlet

-

Español: Jabalina/ toma de tierra

English: Electrical Grounding

Herramientas / Tools / Gadgets

-

Español: Pinza / Alicate

English: Pliers

-

Español: Destornillador eléctrico

English: Screw Gun

-

Español: Destornillador / Desarmador

English: Screwdriver

-

Español: Tester / Multímetro

English: Tester/Multi Meter

-

Español: Arandela

English: Rack Screw/Washer

-

Español: Tuerca

English: Locknut

-

Español: Probador de cables

English: Sniffer/Sender

-

Español: Pasta para soldar

English: Solder Paste

-

Español: Cautin / Soldador

English: Soldering Iron

Artículos de oficina / Office supplies

-

Español: Teipe

English: Electrical Tape

-

Español: Tirro

English: Gaff Tape

-

Español: Marcador permanente

English: Sharpie

-

Español: Teipe de fricción

Grip/Friction Tape

-

Español: Cierre mágico

English: Velcro

-

Español: Tirrap / cinta de amarre

English: Tie-Wraps

-

Español: Etiquetador

English: P-Touch

-

Español: Cinta de embalar

English: Strapping Tape

-

Español: Cinta adhesiva / Cinta plástica

English: Scotch Tape

Acciones / Actions

-

Español: Ingeniero de sala / Centro de sala

Front of House (FOH)

-

Español: Organizar/ Peinar cables

English: To Loom Cables

-

Español: Organizar/ Peinar cables

English: To Loom Cables

Instrumentos musicales / Musical instruments

-

Español: Púa / uñeta

Pick

-

Español: Bombo

Kick Drum

-

Español: Caja / Tarola / Redoblante

Snare Drum

-

Español: Entrada de Jack

Pick Up

-

Español: Clavijera

Head Stock

-

Español: Clavijera

English: Upright Bass

Medidas / Mesurements

| 1.5m | 5 feet |

| 3m | 10 feet |

| 7.6m | 25 feet |

| 15m | 50 feet |

| 30m | 100 feet |

| 50m | 165 feet |

| 100m | 330 feet |