Word Clocks, Clock Masters, SRC, and Digital Clocks

And Why They Matter To You

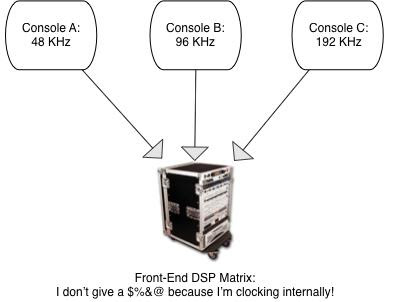

Three digital audio consoles walk into a festival/bar and put in their drink orders. The bartender/front-end processor says, “You can order whatever you want, but I’m going to determine when you drink it.” In the modern audio world, we are able to keep our signal chain in the digital realm from the microphone to the loudspeaker longer without hopping back and forth through analog-to-digital (and vice versa) converters. In looking at our digital signal flow there are some important concepts to keep in mind when designing a system. In order to keep digital artifacts from rearing their ugly heads amongst our delivery of crispy, pristine audio, we must consider our application of sample rate conversions and clock sources.

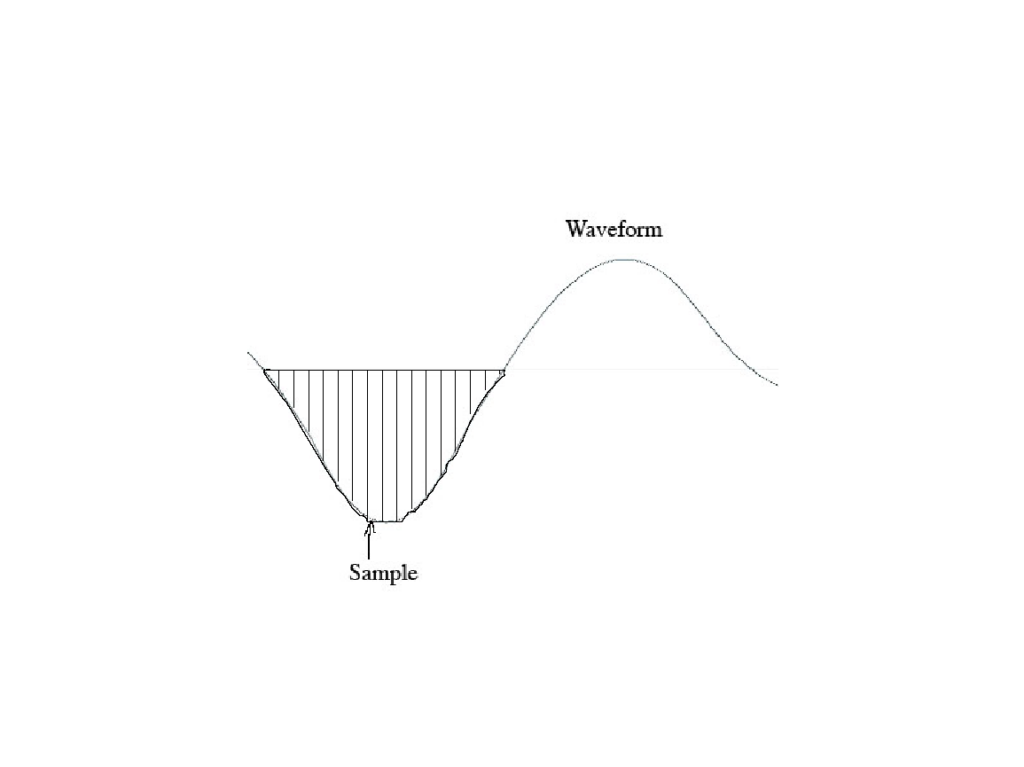

Let’s back up a bit to define some basic terminology: What is a sample rate? What is the Nyquist frequency? What is bit depth? If we take a period of one second of a waveform and chop it up into digital samples, the number of “chops” per second is our sample rate. For example, the common sample rates of 44.1 KHz, 48 KHz, and 192 KHz refer to 44,100 samples per second; 48,000 samples per second; and 192,000 samples per second.

Why do these specific numbers matter you may ask? This brings us to the concept of the Nyquist theorem and Nyquist frequency:

“The Nyquist Theorem states that in order to adequately reproduce a signal it should be periodically sampled at a rate that is 2X the highest frequency you wish to record.”

(Ruzin, 2009)*.

*Sampling theory is not just for audio, it applies to imaging too! See references

So if the human ear can hear 20Hz-20kHz, then in theory in order to reproduce the frequency spectrum of the human ear, the minimum sample rate must be 40,000 samples per second. Soooo why don’t we have sample rates of 40 KHz? Well, the short answer is that it doesn’t sound very good. The long answer is that it doesn’t sound good because the frequency response of the sampled waveform is affected by frequencies above the Nyquist frequency due to aliasing. According to “Introduction to Computer Music: Volume One”, by Professor Jeffrey Hass of Indiana University, these partials or overtones above the sample frequency range are “mirrored the same distance below the Nyquist frequency as the originals were above it, at the original amplitudes” (2017-2018). This means that those frequencies sampled above the range of human hearing can affect the frequency response of our audible bandwidth given high enough amplitude! So without going down the rabbit hole of recording music history, CDs, and DVDs, you can see part of the reasoning behind these higher sample rates is to provide better spectral bandwidth for what us humans can perceive. Another important term for us to discuss here is bit depth and word length when talking about digital audio.

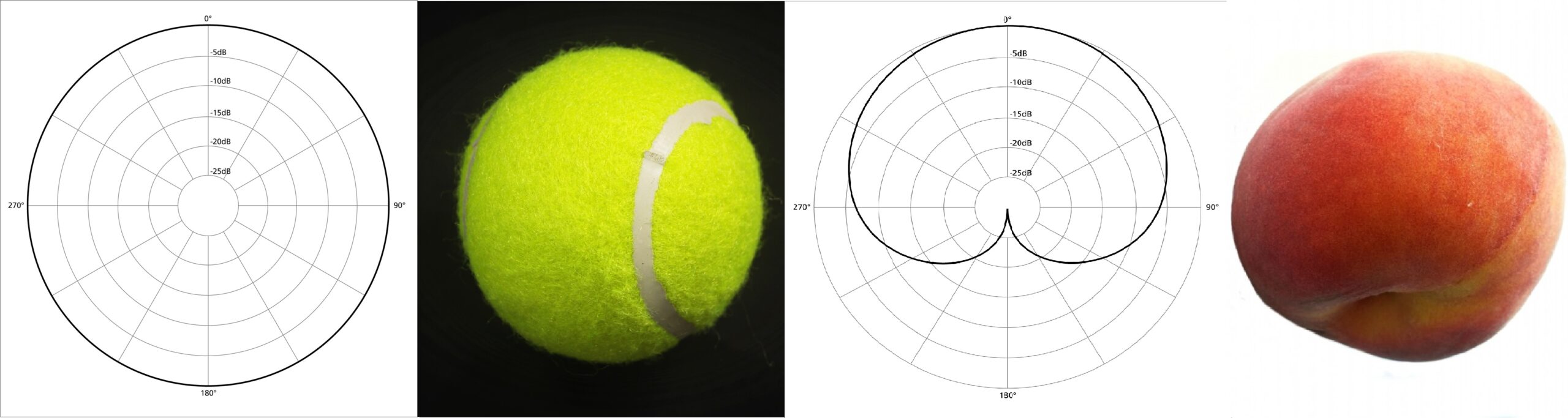

Not only is the integrity of our digital waveform affected by the minimum number of samples per second, but bit depth affects it as well. Think of bit depth as the “size” of the “chops” of our waveform where the higher the bit depth, the greater discretization of our samples. Imagine you are painting a landscape with dots of paint: if you used large dots to draw this landscape, the image would be chunkier and perhaps it would be harder to interpret the image being conveyed. As you paint with smaller and smaller dots closer together, the dots start approaching the characteristics of lines the smaller and closer together they get. As a result, the level of articulation within the drawing significantly increases.

When you have higher bit depths, the waveform is “chopped” into smaller pieces creating increased articulation of the signal. Each chop is described by a “word” in the digital realm that translates to a computer value by the device doing the sampling. The word length or bit depth describes in computer language to the device how discrete and fine to make the dots in the painting. So who is telling these audio devices when to start taking samples and at what rates to do so? Here is where the device’s internal clock comes in.

Every computer device from your laptop to your USB audio interface has some sort of clock in it whether it’s in the processor’s logic board or in a separate chip. This clock acts kind of like a police officer in the middle of an intersection directing the traffic of bits based on time in your computer. You can imagine how mission-critical this is, especially for an audio device, because our entire existence in the audio world lives as a function of the time domain. If an analog signal from a microphone is going to be converted into a digital signal at a given sample rate, the clock inside the device with the analog-to-digital and digital-to-analog converter needs to “keep time” for that sampling rate so that all the electronic signals traveling through the device don’t turn into a mush of cars slamming into each other at random intervals of an intersection. Chances are if you have spent enough time with digital audio, you have come into some situation where there was a sample rate discrepancy or clock slipping error that reared its ugly head and the only solution is to get the clocks of the devices in sync or change the sample rates to be consistent throughout the signal chain.

One of the solutions for keeping all these devices in line is to use an external word clock. Many consoles, recording interfaces, and other digital audio devices allow the use of an external clocking device to act as the “master” for everything downstream of it. Some engineers claim the sonic benefits of using an external clock for increased fidelity in the system since the idea is that all the converters in the downstream devices connected to the external clock are beginning their samples at the same time. Yet regardless of whether you use an external clock or not, the MOST important thing to know is WHO/WHAT is acting as the clock master.

Let’s go back to our opening joke of this blog about the different consoles walking into a festival, umm I mean bar. Let’s say you have a PA being driven via the AES/EBU standard and a drive rack at FOH with a processor that is acting as a matrix for all the guest consoles/devices into the system. If a guest console comes in running at 96 KHz, another at 48 KHz, another at 192 KHz, and the system is being driven via AES at 96 KHz, for the sake of this discussion, who is determining where the samples of the electronic signals being shipped around start and end? Aren’t there going to be bits “lost” since one console is operating at one sample rate and another at a totally different one? I think now is the time to bring up the topic of SRC or “Sample Rate Conversion”.

My favorite expression in the industry is, “There is no such thing as a free lunch” because life really is a game of balancing compromises for the good and the bad. Some party in the above scenario is going to have to yield to the traffic of a master clock source or cars are going to start slamming into each other in the form of digital artifacts, i.e. “pops” and “clicks”. Fortunately for us, manufacturers have thought of this for the most part. Somewhere in a given digital device’s signal chain they put a sample rate converter to match the other device chained to it so that this traffic jam doesn’t happen. Whether this sample rate conversion happens at the input or the output and synchronously or asynchronously of the other device is manufacturer specific.

What YOU need to understand as the human deploying these devices is what device is going to be the police officer directing the traffic. Sure, there is a likelihood that if you leave these devices to sort their sample rate conversions out for themselves there may not be any clock slip errors and everyone can pat themselves on the back that they made it through this hellish intersection safe and sound. After all, these manufacturers have put a lot of R&D into making sure their devices work flawlessly in these scenarios…right? Well, as a system designer, we have to look at what we have control over in our system to try and eliminate the factors that could create errors based on the lowest common denominator.

Let’s consider several scenarios of how we can use our trusty common sense and our newfound understanding of clocks to determine an appropriate selection of a clock master source for our system. Going back to our bartending-festival scenario, if all these consoles operating at different sample rates are being fed into one system for the PA, it makes sense for a front-end processor that is taking in all these consoles to operate its clock internally and independently. If the sample rate conversion happens internally in the front-end processor and independent of the input, then it doesn’t really care what sample rate comes into it because it all gets converted to match the 96 KHz sample rate at its output to AES.

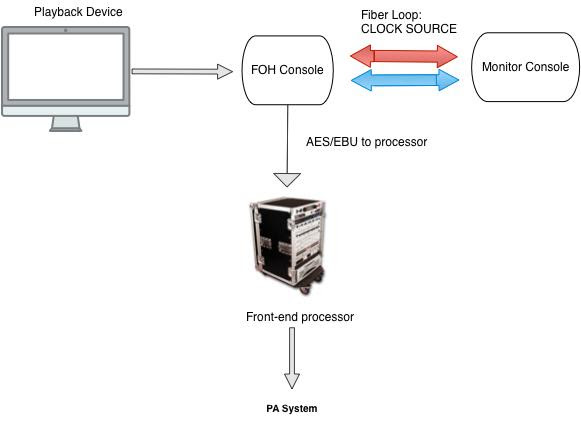

In another scenario, let’s say we have a control package where the FOH and monitor desk are operating on a fiber loop and the engineers are also operating playback devices that are gathering time domain-related data from that fiber loop. The FOH console is feeding a processor in a drive rack via AES that in turn feeds a PA system. In this scenario, it makes the most sense for the fiber loop to be the clock source and the front-end processor to gather clock and SRC data from the AES input of the console upstream of it because if you think about it as a flow chart, all the source data is coming back to the fiber loop. In a way, you could think of where the clock master comes from to be the delegation of the police officer that has the most influence on the audio path under discussion.

As digital audio expands further into the world of networked audio, the concept of a clock master becomes increasingly important to understanding signal processing when you dive into the realms of protocols such as AVB or Dante. Our electronic signal turns into data packets on a network stream and the network itself starts determining where the best clock source is coming from and can even switch between clock masters if one were to fail. (For more information check out www.audinate.com for info on Dante and www.avnu.org for info on AVB). As technology progresses and computers get increasingly more capable for large amounts of digital signal processing, it will be interesting to see how the manifestation of fidelity correlates to better sample rates, bit-perfect converters, and how we can continue to seek perfection in the representation of a beautiful analog waveform in the digital realm.

The views in this blog are for educational purposes only and the opinion of the author alone and not to be interpreted as an endorsement or reflect the views of the aforementioned sources.

Resources:

Hass, Jeffrey. 2017-2018. Chapter Five: Digital Audio. Introduction to Computer Music: Volume One. Indiana University. https://cecm.indiana.edu/etext/digital_audio/chapter5_nyquist.shtml

Ruzin, Steven. 2009, April 9. Capturing Images. UC Berkeley. http://microscopy.berkeley.edu/courses/dib/sections/02Images/sampling.html

www.audinate.com

**Omnigraffle stencils by Jorge Rosas: https://www.graffletopia.com/stencils/435