It can be both an exciting and terrifying feeling being a new editor. On one hand, you are thrilled to start editing on a project! On the other hand, you don’t know where to begin. I interviewed a few editors on our team who know exactly how you’re feeling and can give you some insight into their editorial approach.

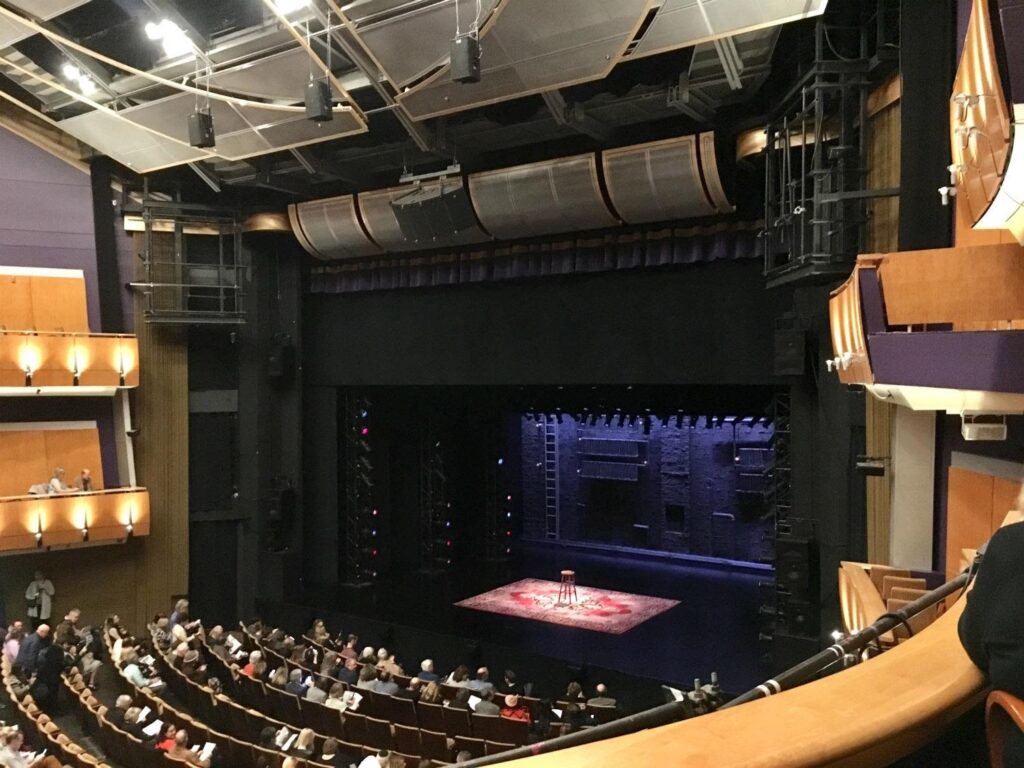

I thought it would be easiest for our readers to visually see a reference clip, so I had our editors answer a few questions with this fun short! I think I want a pet camel after watching this…Check it out below:

If you were editing this what would your editorial approach be/what would you tackle first?

Brad– First, I’d do all of the BG’s and ambiences. They’d give me a good base layer to go off of and help set the vibe for the rest of my edit. Once finished, I’d also have a visual aid of any new locations and potential scene changes just by looking at my background tracks.

Second, I’d go through the clip and see if there is anything I might need to record or design. For example, perhaps the camel or any other vocal elements. Maybe the cell phone/remote control beeping.

Third, once I have a good base layer of BGs, and my recording and design files ready to incorporate, I’m going to go ahead and start my edit. I don’t have any particular order of things or passes that I do since I break up my work by time, rather than category.

Tess– Whenever I start a new project I always watch the whole thing down first and then set up my time management. Since I’ll go more into detail about that in your second question, I’ll just skip those steps and get right into editorial. I usually like to work chronologically, but there are some exceptions. I find it difficult to keep animal/creature vocals sounding like they come from the same character unless I cut them all in one pass, so for this clip, I’d probably just start with the Camel vocals. After that, I’d probably design the beeps from the remote. I like to make every sound I cut completely unique to the project I’m working on (if possible) and these beeps are an easy and fun one to design. I like to use a lot of different synths on my iPad when designing beeps or sci-fi elements, so I’d likely start there. Once I design a library of beeps that sound like they could all come from the same remote, I’ll cut them in. Footsteps are another element that I’d cut all in one pass, but we’re pretty lucky here at Boom Box that Carol does an amazing job of cutting all of our foley. Once those sounds are edited in, I’d just cut chronologically. A big part of this clip is all of the stone movement, so I’d probably plan my days so that I’d cut all of that in one day, but I can go more into that in your second question.

Jacob– If I were responsible for covering all sound effects for this clip, I would start with creating some background layers. This particular short would be very fast because they are in one location the whole time! I often like to do this at the beginning of my day or edit, because it helps me get a sense of where the cuts are, and it helps the dry sound effects feel a bit more natural when I start adding them later. Next, I would tackle all the Foley elements, starting with footsteps and hand grabs, and rubs. This would also be pretty quick. Then I would move on to covering all the rest of the sound effects in one pass, dividing up the length of the short by the hours I have to complete it, and setting benchmarks. I use this when editing as a way to make sure I am working at a good pace to be able to complete the editorial and have time to review it, clean things up, and do some pre-mixing afterward. In certain cases, where there is a huge amount of original design, like an episode where there are whacky unusual vehicles or space ships flying around, I might set aside an hour or two at the start to create a library of the effects I need.

Katie– I personally like to work chronologically, so naturally, I would start with the very first thing I see. If there were a recurring, design-heavy element like a spaceship or time machine, I would work on that from start to finish to save time, rather than chronologically. It would be time-consuming to design little parts of something that may evolve later in the episode. But for this short, I would start with the very first action.

Assuming this was longer and given more than a day to do, how would you go about the editorial time management wise?

Brad– I’d figure out the total run time and divide by the number of days I have to get the project done. The resulting number is how much I need to get done per day. I edit linearly so I’d start at the beginning and edit to the according to time code I need to get done for the day. I do, however, edit linearly by scene. Admittedly, since my attention span isn’t long enough to digest one large clip, and to invoke a sense of accomplishment, I will edit from beginning to end a single scene. Once that scene is done, I’ll move on to the next. This also creates neat stopping points at the end of the day. Just make sure to go back and watch the entire thing to make sure the scenes flow together well.

Tess– I always start my projects by breaking them down by day. Usually, I just divide the length of the project by the number of days I have to work on it, minus one day, to determine how much content I need to get done per day. For instance, if this clip were a 22-minute episode and I have 7 days to cut it, I would divide 22 by 6 and determine I need to complete a little over 3 and half minutes per day. If I follow that schedule perfectly then I have a full extra day to accomplish notes or rewatch my work to see if there is anything I could sweeten or clean up.

After I determine how much content I need to complete each day, I divide up the project/clip into groups of that size. I like to color-code them as well. I usually just group them chronologically, however, if there is a specific element that happens multiple times throughout the project (like the stone movement in this clip) I’ll try to divide the project so that I cut all of those similar elements on the same day. This picture is an example of what a clip looks like when I get started. Each color would be a single day’s worth of work.

Jacob– For a longer piece, my strategy would be largely the same, except that I might split the foley and backgrounds over both days, doing some at the start of each day. I stand by the strategy of chunking out the episode into days or hours, as this allows you to get a clear picture of your progress, and prevents panic moments when a deadline looms and you discover you have only cut ⅓ of the episode instead of ¾! So for a two-day edit, I would divide the episode into 2, maybe with the second day having slightly less time. If you like to be extra precise, you can further divide each day up into chunks of what you need to complete each hour. I always leave an extra hour or two at the end of my last day for a watch down, so I can make balance adjustments, recheck client notes, and catch any missing elements or mistakes.

Katie– I like to estimate approximately how many minutes I need to cut per day to finish on my given deadline, and make large blank clips above that space and color them differently for each day. As I go, I turn the clips green to indicate that section is done. It’s an easy visual representation of how much is done, and an easy indicator if I am falling behind. If it’s a several-day edit, I like to give myself at least a couple of hours or even a day to comb through the episode and polish it. It’s very easy to miss obvious elements when you’re working frame by frame. I watch it back several times to make sure everything is covered. I also like to watch it back with any notes I was given to make sure they are all addressed.

What would be your advice to new sfx editors figuring out an editorial process that works for them?

Brad– Watch other editors edit. It’s how I learned what works for me and how most people learn to edit via school or internships/etc. There’s more than one way to do practically everything, and if you watch enough people do their thing the way they do it, you can pick and choose what you like from different peoples’ workflows. You create your own repertoire of tricks and methods and expand it over time.

Tess– The best advice I can give someone is to find a time management tactic that works for them. The worst thing you can do in the professional world is not complete your work thoughtfully and on time. If you aren’t sure what will work for you, try my tactic of grouping by day, or ask other professionals how they manage their time and try it their way. There are so many ways to manage your time, so just keep an open mind and find the method that works for you. Also, don’t get intimidated if 3.5 min/day seems like a lot to you at this stage in your editing career. You might have to hustle at first, but the more you edit and know your library, the faster you’ll become. On that same note, don’t be afraid to try new things in order to speed up your editing skills. When I first started at Boom Box, Jeff suggested I map my mouse buttons to the different tools in Pro Tools. At first, I was a little clumsy in getting used to switching my tools with my mouse, but in the long run, it made me so much faster.

Jacob– For newer editors, I would say it is important to figure out how fast you can really work, and allow yourself extra time. I was definitely much slower when I first started, and when I started scheduling my time and realized how much I could realistically get done, it became much easier to complete my work on time. It’s also important to understand what time of day you tend to work best and fastest. I tend to be most creative and efficient in the early morning and evening, slowing down in the middle of the day when communications can distract me and my brain needs breaks. If you can learn how you work best, you can plan to do your design work or complicated cutting when you are fresh and most likely to produce the best most interesting work.

Katie– Give yourself plenty of time when scheduling out what you’re going to need to cut each day. Don’t treat a three-minute action scene the same as a three-minute dialogue scene in the time that you give yourself. Cut just a little bit more than you need every day so at the very end you can comb through and add extra details or spend more time in areas that could use it.

As you can see, there’s no right or wrong way to approach sound effects editorial! You need to find what works best for you and you WILL figure it out as you continue to edit more and more.

If you liked this blog, you should check out these other posts that are helpful for new editors:

HOW TO CRUSH YOUR FIRST GIG AS A SOUND EDITOR

LUNCH AND LEARN: MAC KEYBOARD SHORTCUTS EVERY SOUND EDITOR SHOULD KNOW

BACKGROUNDS, AMBIENCES OR SOUND EFFECTS?

THREE BASIC SKILLS EVERY SOUND EDITOR MUST MASTER

STAY ON TRACK! FIVE TIPS FOR IMPROVING CREATIVE PRODUCTIVITY

A COLLABORATIVE POST WRITTEN BY BOOM BOX POST

A COLLABORATIVE POST WRITTEN BY BOOM BOX POST