I don’t have a mathematical bone in my body, but a prime number for me signifies a certain setting apart from the regular, the symmetry and patterns of who we are and who we might be. A couple of months ago, I talked about being in the margins musically and socially and I still hold this to be true without giving myself a sense of uniqueness. I mean we are all unique in our own way, but I just feel that a prime number represents me. And, feeling this way, an odd 17, a queer woman who makes music with noise, and a fascist prime minister in prospect, It’s all starting to feel just a little bit like discrimination. Maybe not a good time to be a prime number; but I am valient.

To my guiding stars Truth and Justice, I am adding Liberty. For example, I’m single and only attracted to women. However, here in Italy I can have a civil union with a woman but not marriage; neither could we adopt children. I don’t want to marry in a church and wear white; I don’t particularly want to adopt children. What I demand are the same rights in marriage as a heterosexual couple. If not, it is discrimination.

Getting back to Prime 17, it all started with some high-blown fantasy of starting my own record label: Hah! I’m not sure where the number idea came from but when it did, I knew that it was just right. And feeling ‘just right’ is all I ask of life. The rest is up to me…

That’s the personal bit done except to say that the queen of my country died on my birthday. Where was I? Here, writing the names of the 74 femicides (so far this year). About a dozen of us from Non Una di Meno were in Piazza Castello in the center of Turin, to commemorate the passing of these women. One, in particular, moved me: Unknown woman found murdered, her body mutilated and stuffed in a suitcase and dumped in the river Po. While I felt some sadness for the queen, who had been there my entire life, I really wept for this unknown woman. Was I the only person weeping for her death at the hands of … it was a man since mutilation of the corpse is often the case in femicides. Who was she, who will miss her? Was she a someone’s mother, or someone’s sister, certainly someone’s daughter? Who will weep for her? I still think about her, and I think about the 22-year-old girl beaten to death by the morality police in Iran for not wearing her headscarf correctly; and of the two sisters 17 and 15 raped and hung from a tree in India; no one should care since they are low caste ‘untouchables’. And yet my heart breaks with every hurt against women. So here I am, saying, ‘Sister, you are not alone!’

In the preceding blogs, I’ve talked a lot about the kind of music I compose. I’ve talked about experimental music, and I did a lot of experimenting and auditioning of sounds to use in this piece, based on The Book of Tea. However, I still see myself as a ‘Sound Artist’. So, as a sound artist, whose materials are mainly noises with no written score to follow, I want to explain how I work from airy ideas to Sound Art..

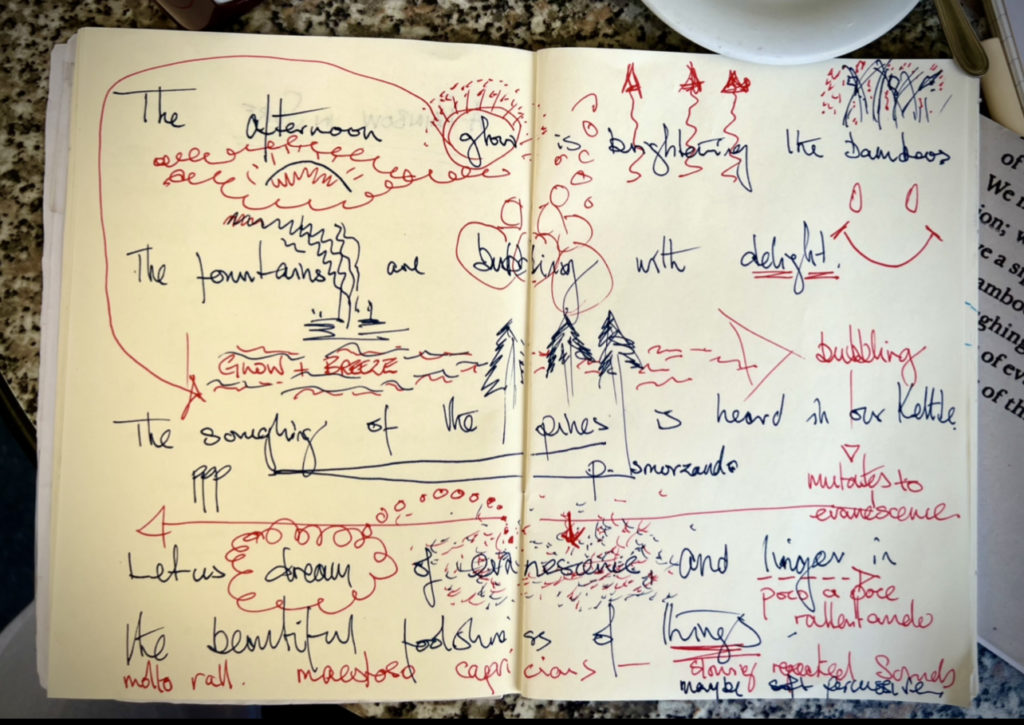

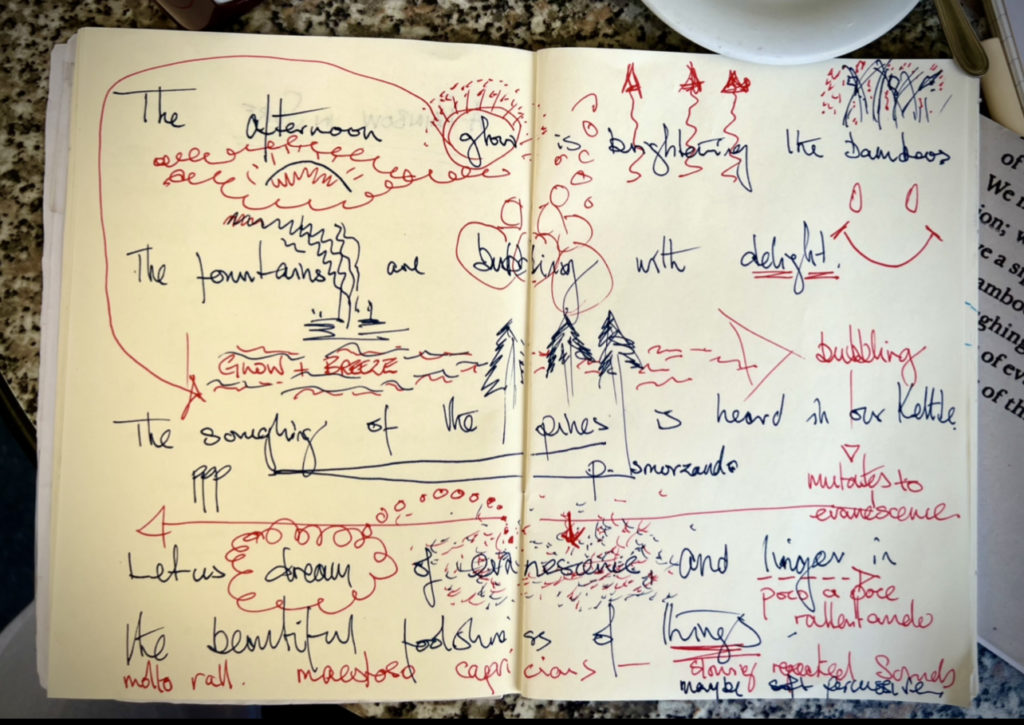

I generally work from a narrative that I visualize as loose situations in my mind and then sketch something down so that I have a starting point. This was sketched at the pavement bar in front of my apartment in Turin in about half an hour, my ADHD creative surge fueled by an espresso coffee.

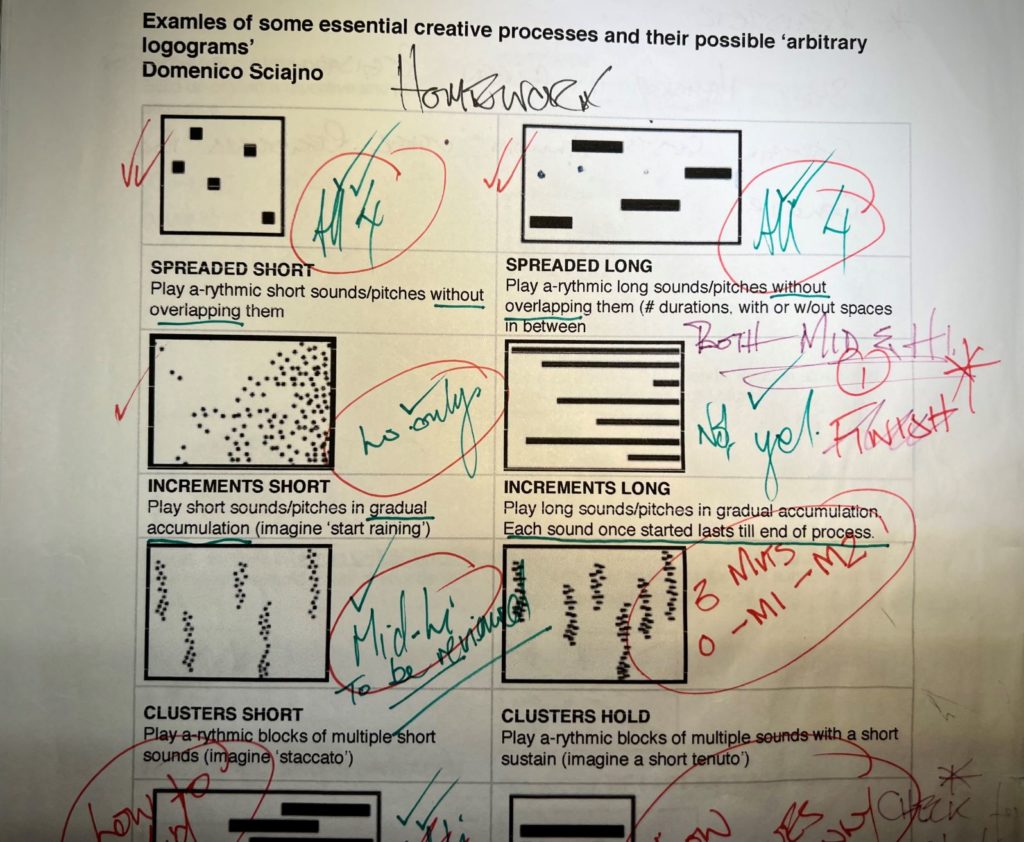

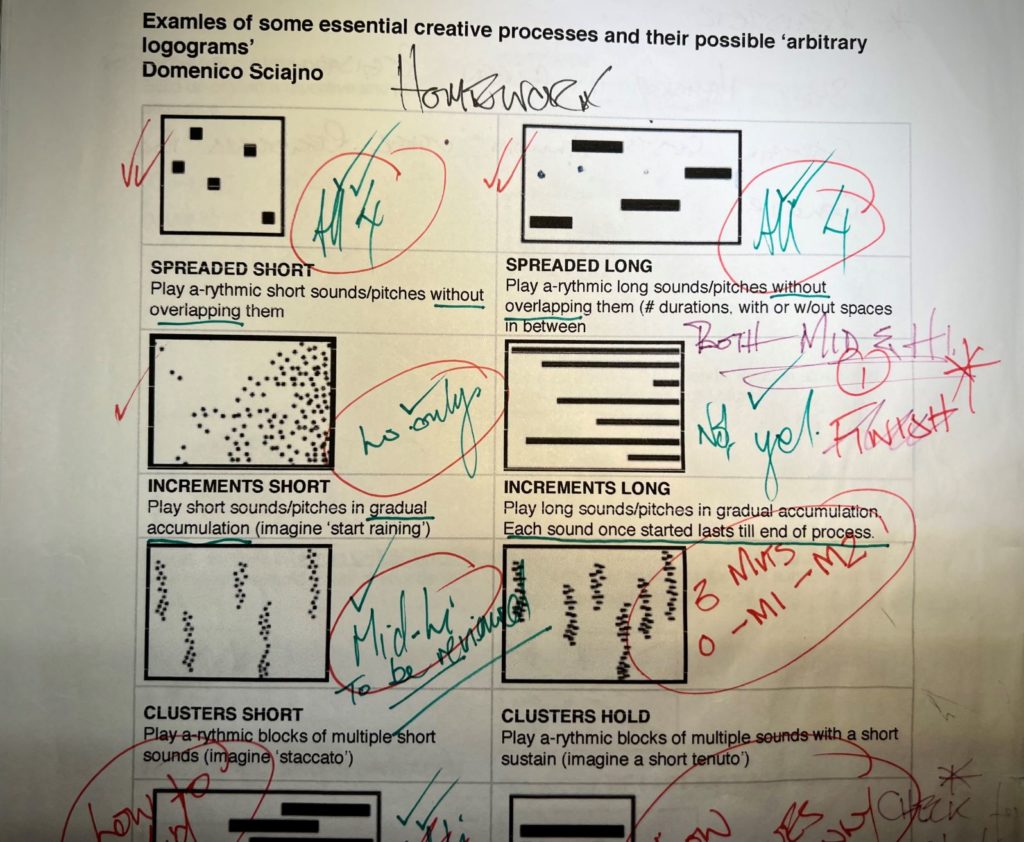

From this sketch, I begin to hear the kinds of sounds that will represent my narrative and my interpretation of it and so, I begin the first stage of finding and creating my sound (noise) samples. When I was at the Turin Conservatoire, learning to use my experience of working with tape to create musique concrète, but with a computer, we worked in a systematic way of collecting sounds according to their character. Not only that but we, had to spectrum filter them into lo; mid; mid-hi; hi as a minimum and then transpose them into all notes of the chromatic scale: I started this blog by saying that I didn’t have a mathematical bone in my body, but somehow, I worked out that I ended up with 48 .wav files for each sound sample:

However, these days I tend to create sound samples on demand. For example, I wanted to create a sound wash, not quite a drone, for the first line: The afternoon glow is brightening the bamboos. First of all, ‘afternoon glow’ and Debussy’s L’aprés Midi d’un Faune came to mind, and I imagined something lyrical and modal to set the scene. I imagined bamboo growing by the roadside and the wind catching it making them rattle against each other, and that for this movement a breeze would be needed. So, my first task was to create a ‘breeze’.

In my distant past, I’ve played Viola da gambe; Classical, Jazz and Bass guitar, orchestral percussion, trumpet, and even flirted with the ‘misery stick’ B flat clarinet for the uninitiated. As an aside, Puccini made great use of the clarinet in his operas but then: misery, misery, most of his heroines died, Mimi in La Bohème, and Tosca in Tosca. Not sure about the rest but great music, though I’m sure I would have hated him. All this just to tell you that I’d never played the flute before not even the bamboo one I used to record my acoustic sound sample for the breeze. My lack of skills was a blessing otherwise I might have played some proper notes instead of the breathiness and slight hint of pitch. Now the latter was useful since after copying the sample five times and then reversing it and copying those five times I had ten breathy fluting sounds of about four minutes. Unlike many reversed sound samples which have that characteristic crescendo and then a reverse attack that ends the crescendo abruptly; this reversed clip (I’ll stick with the word clip as used in Audition rather than stem) had very little pronounced attacks but had natural spaced sounds according to where I breathed when recording. Incidentally, I don’t have a proper microphone, so I use my Zoom H6 through my interface and generally record to Audition.

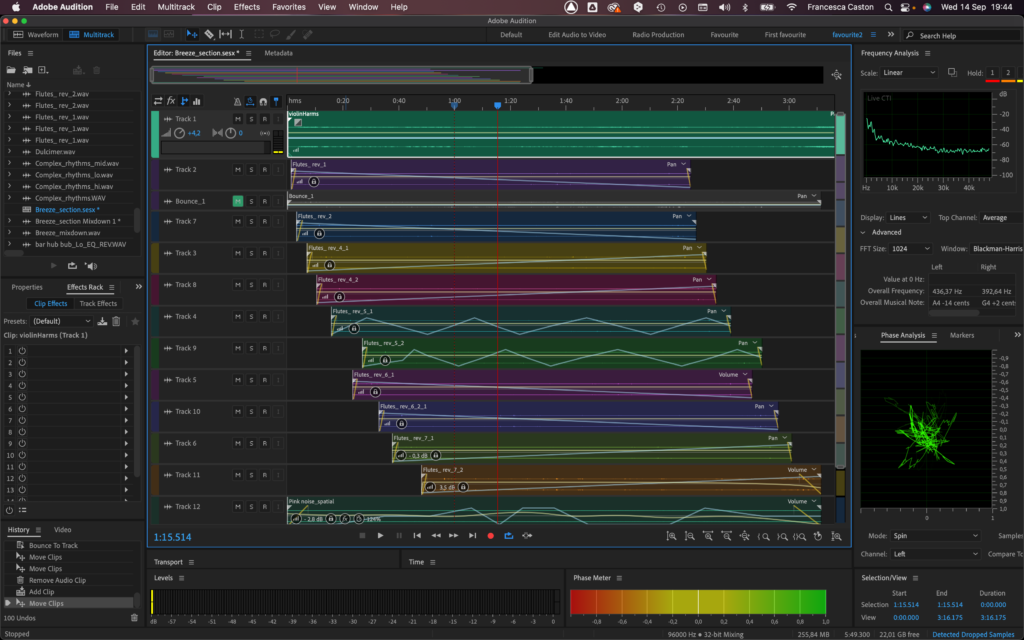

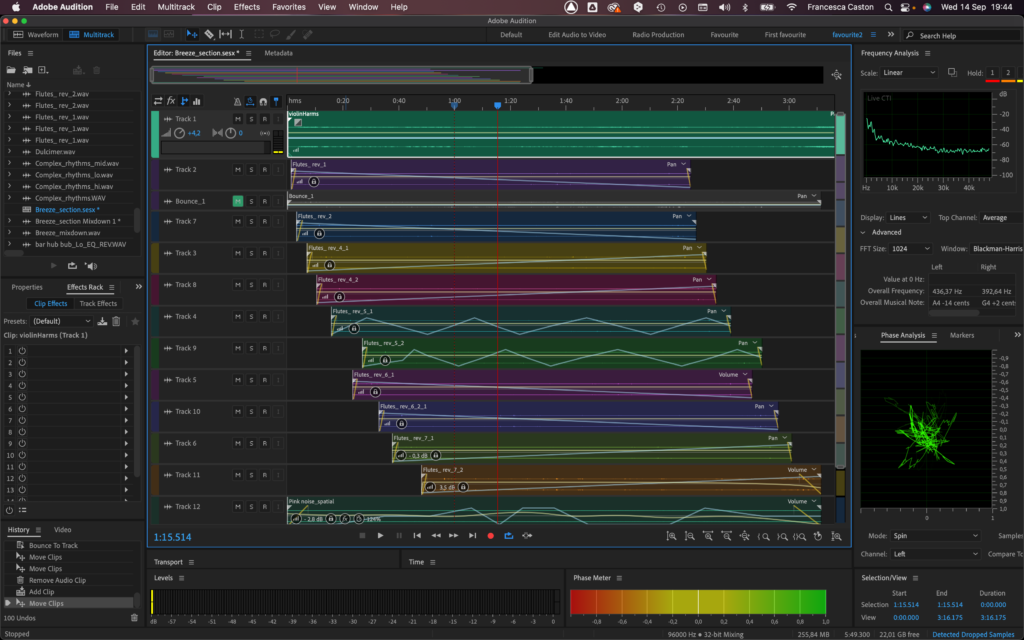

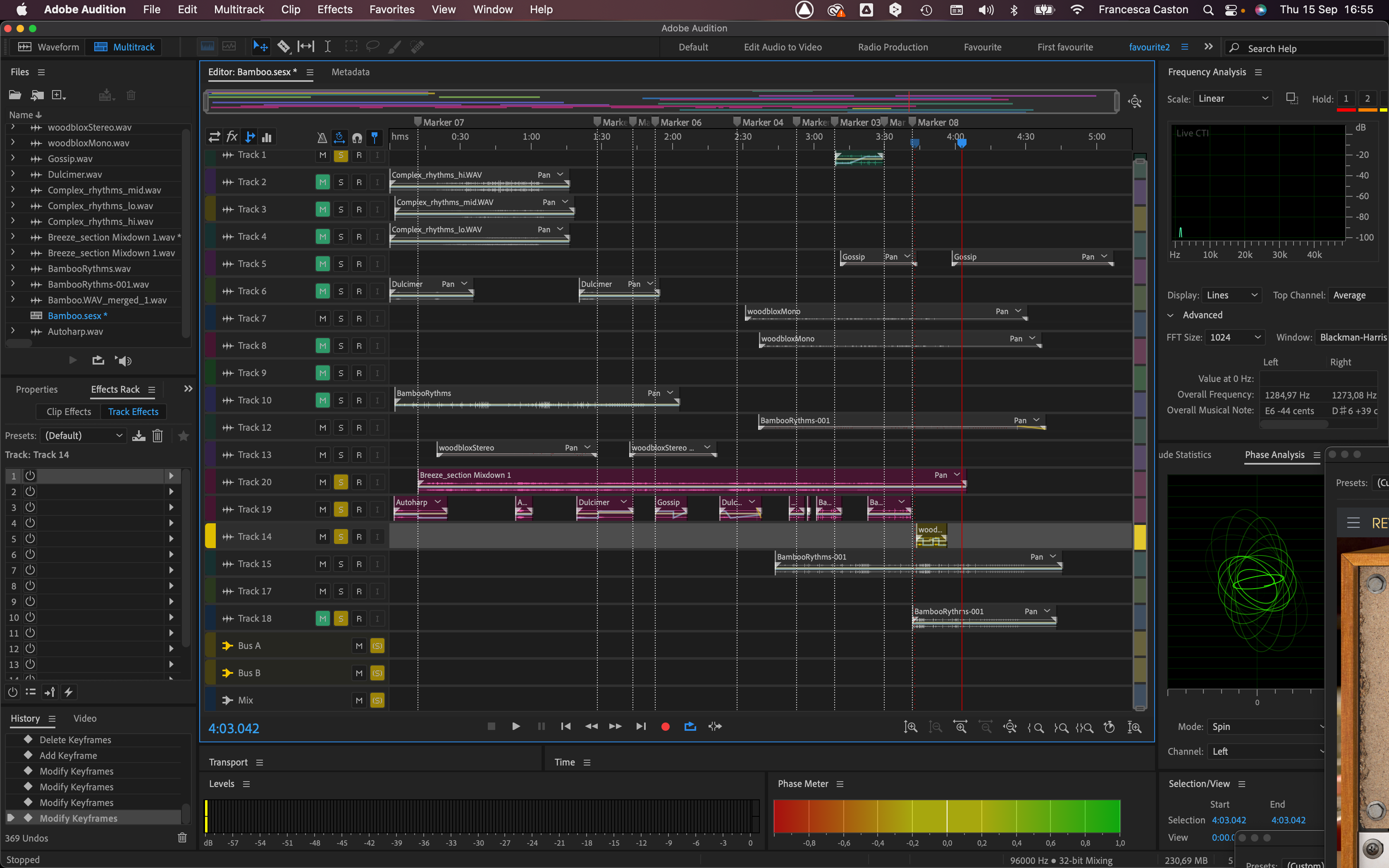

I then transposed all of them to different pitches within a two-octave range so I had a chordal cluster that would not be any recognizable chord but since I deal in noise, it suits my needs perfectly. What is my need here? I want to suggest a breeze, but I want to suggest a hint of musicality as well. For this, after listening to a lot of samples, I used Spitfire Audio’s Intimate strings samples, and high violin harmonics (track 1); while below, (track 12) I generated some Pink Noise which I experimented with and, once balanced within the mix, automated the volume and panning so that the sound was shifting in and out of perspective; I later did much the same with the violin harmonics. The illustration below shows the tracks laid out and staggered entries. Now, remember that five of the ten flute tracks have been reversed. in this way there are no unison sounds and any one of the individual sounds within the four minutes will occur ten times at different pitches and in different places and half will be reversed and in a different position of the stereo stage since I have also automated the panning of each track. Lastly, each clip has two or three effects added to change the nature of each sound that makes up the whole. In this way, there is continuous movement within the drone/wash which requires ‘deep listening’ at times to perceive the changes of color within.

The following Image shows the same Breeze section in the mixing view, which I find useful in the later stages so that I can listen without being distracted by looking at the clips. One thing you will notice, however, are the effects which are pitch shifter and De noise for all the tracks plus the addition of different kinds of EQ, echo/delay, notch filter, compression with the addition of a reverb unit on a bus track etc.

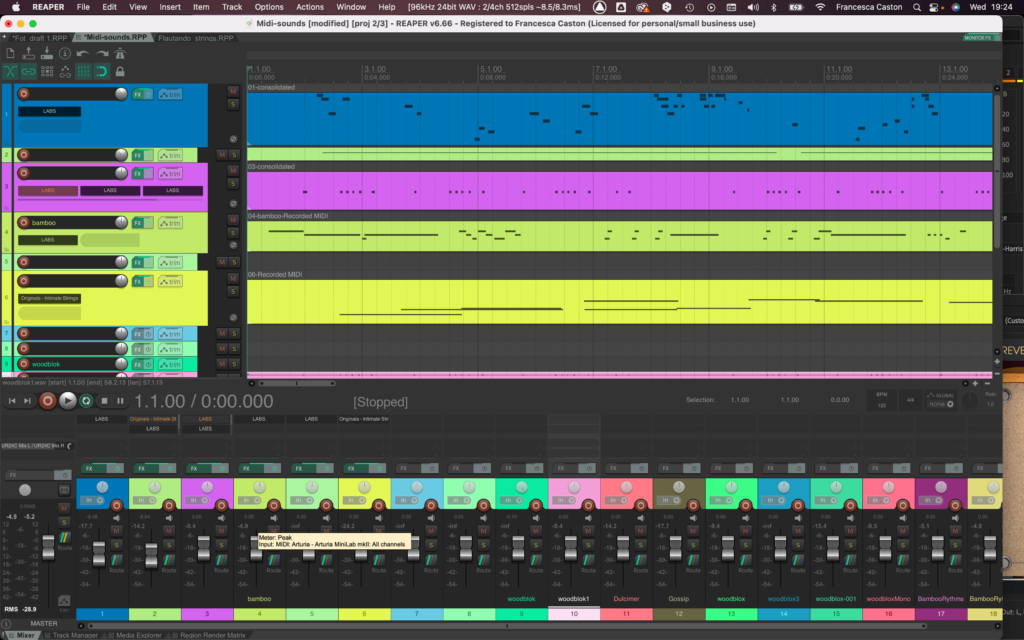

So those are the main elements of the construction of the wash which was eventually mixed down to a wav file. I mentioned violins and I also made use of the Autoharp and the dulcimer. But since Audition does not have MIDI, I used Reaper to record these instruments. So, the only problem is recording the instruments separately and then render them as wavs and then take them to Audition.

I prefer to ‘compose’ in Audition for various reasons. One thing I do, as a matter of habit, is to let the current state of a particular section play on repeat while I get on with other stuff, occasionally paying more attention if I hear something I’m not sure about. For example, on one of the tracks, I applied ‘dub delay’ which sounded quite interesting. However, over repeated listening, it became irritating and created an expectation that Bob Marley would add a vocal… not quite a Japanese afternoon in the countryside, so I changed it.

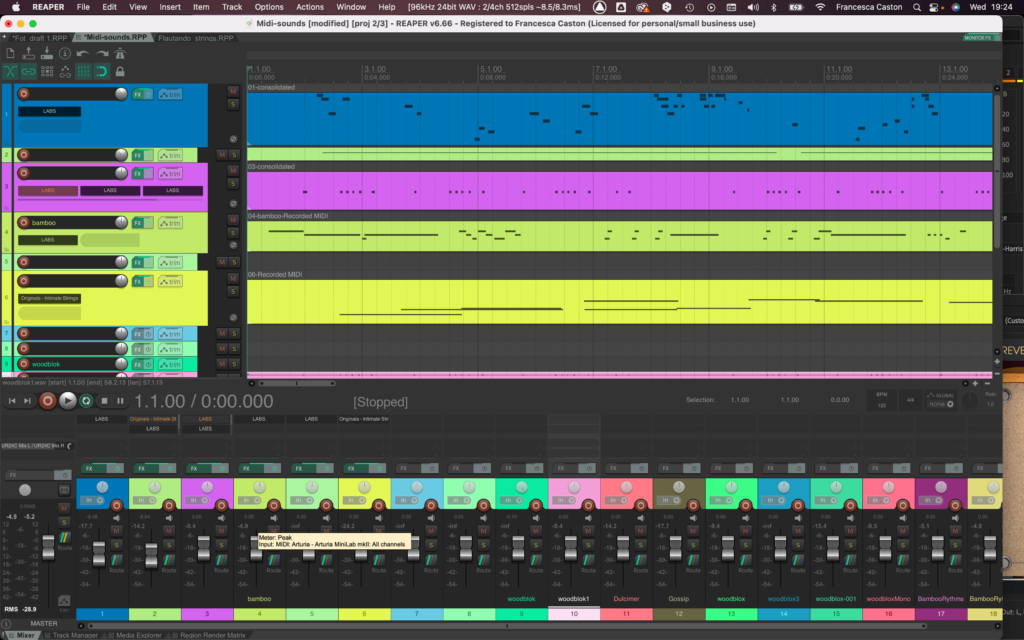

The following image is just a collection of instrumental samples on Reaper: high violins, Autoharp and Dulcimer. Of course, it would have been better if I could have added the instruments in real-time, and maybe, once I become more familiar with Reaper, I might reverse the process: use Audition to create and process my sound files and then take them into Reaper for the compositional process; watch this space!

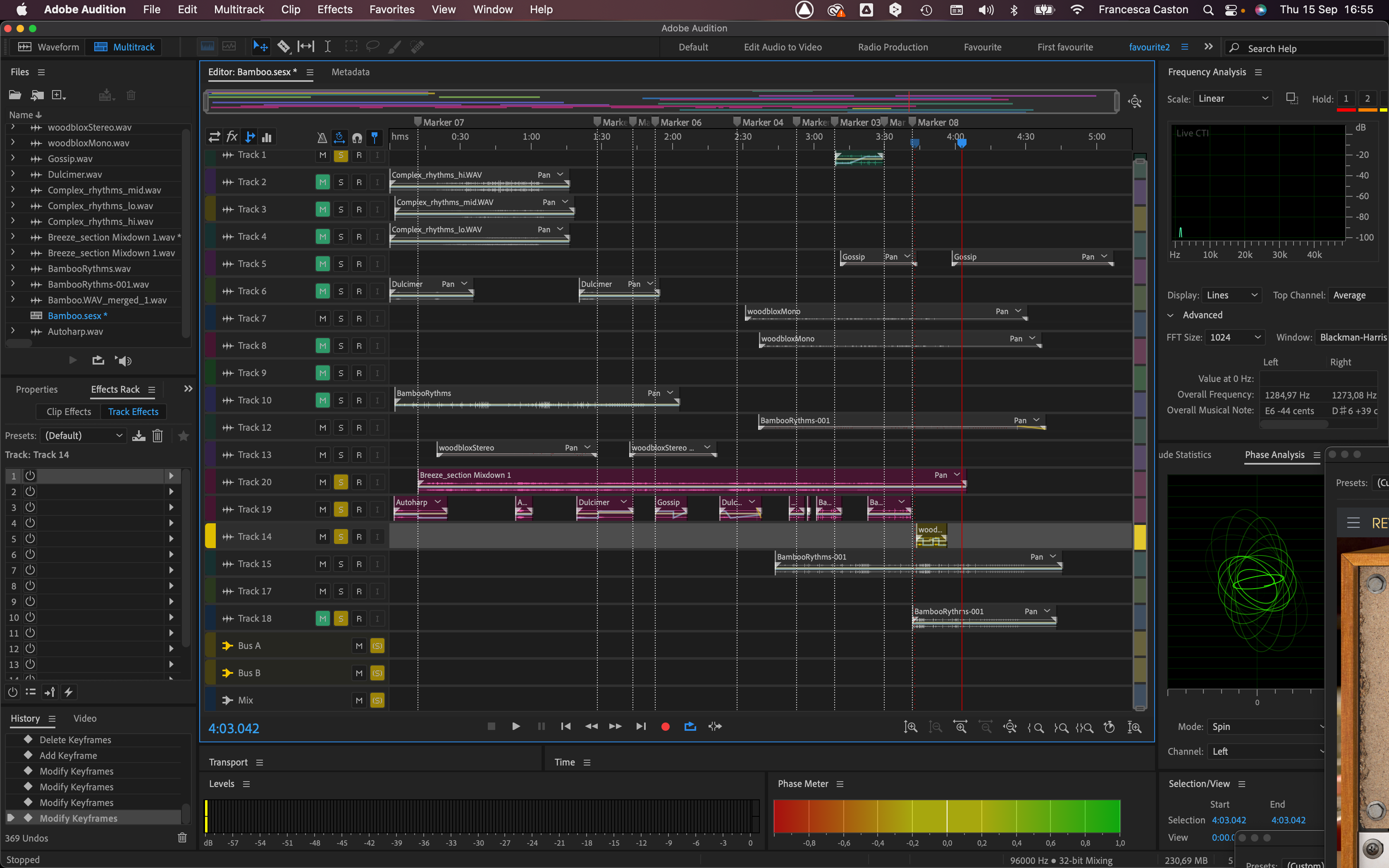

So, let’s talk bamboo, mentioned at the end of the first line. As I have already suggested, I found this passage very evocative not as a faux Japanese image either. Artistically, I imagined the bamboo canes in movement as the result of a warm afternoon breeze. So, I began to think about symbolic representations of ‘afternoon glow’ and the sound of bamboo as light percussive sounds. Therefore, using Reaper and the Spitfire Audio LAB sound samples, I recorded: Autoharp, Dulcimer, Claves, woodblock, abstract voices, and high violin harmonics. In the following figure, the harmonics are already incorporated, along with the pink noise in the “Breeze_section_Mixdown 1”. So, this multi-track session is really a workspace to experiment with the midi instruments, now waveforms, and treat them and place them in a time-space to create a draft mix. So, before placing my breeze sample in its place, on track 20, I made some preliminary adjustments of balance, which in this case is just controlling volumes since the 12 tracks making up the breeze had already been manipulated regarding panning and volume. Once the instruments had been placed at different points, I used the automated volume track to blend the breeze into the individual instrumental entries, for example dipping the volume slightly at the entry of the dulcimer in order to give it space to ‘bloom’. On this ‘Sketch Pad’ I had two bus tracks A and B, both reverb but A slightly drier and B with More resonance; I have to say that I like the Arturia Rev Plate 140 and its pre-sets, ‘Shy Reverb’ is great for keeping things natural. Two were enough since I had my instruments on the drier setting reserving the bouncier reverb on bus B for the claves at the end.

Anyway, my workflow, such as it is, consists of arranging all the elements roughly where they will appear in the finished piece and then: play, listen, play, listen, and them some more. In this case, there was too much percussion; so, by using razor edit (just like the old days of tape) I select the sounds I want and place them where appropriate. Perhaps as a throwback to the days of tape, I often put similar samples on one track which means that I cannot freely use the mixer faders just because one clip goes into the red, for example. In this case, I make panning and volume adjustments on each individual clip. A couple of points that are important to me when using a Digital Audio Work Station as a composition tool is to make sure that each clip has any effects and processing directly on the clip and not the track. In this way, if I copy and proliferate the clip, it will have the processing with it and, should I move a clip to another track; again, it will keep its original processing parameters. To create my mixdown I used only tracks 1, 20, 19, and 14. The remaining tracks, especially 2, 3, and 4 will be used in the following section which is water-based. These three clips are spectrum edits into hi, mid and lo frequencies of water sounds and can be further treated by looping stretching, transposing, etc.

A couple of thoughts: all my mixdown or bounced clips leave a trail of intermediary sound files which at 96000 Hz and32 bit floating point take up a lot of storage. Secondly, this kind of composition is incredibly slow, but I was unusually rather quick with this section perhaps because I aimed for a more transparent and well-spaced texture. I comfort myself with the fact that Éliane Radigue used to spend a year on one work.

Big changes for me. If all goes well, by early spring, I’ll be at the Centro Mexicano para la Música y las Artes Sonoras, Morelia, Michoacán, México, where I hope to find other artists that I can collaborate with. Until then there is The Foolishness of things to finish and I need to become functional in Spanish.

What you see on the screen in fig 6 is available on Soundcloud with the link below.

https://soundcloud.com/francesca-caston/bamboo

Soundgirls te quiero 💜 Sí, también a todas las de Mèxico 🇸🇳